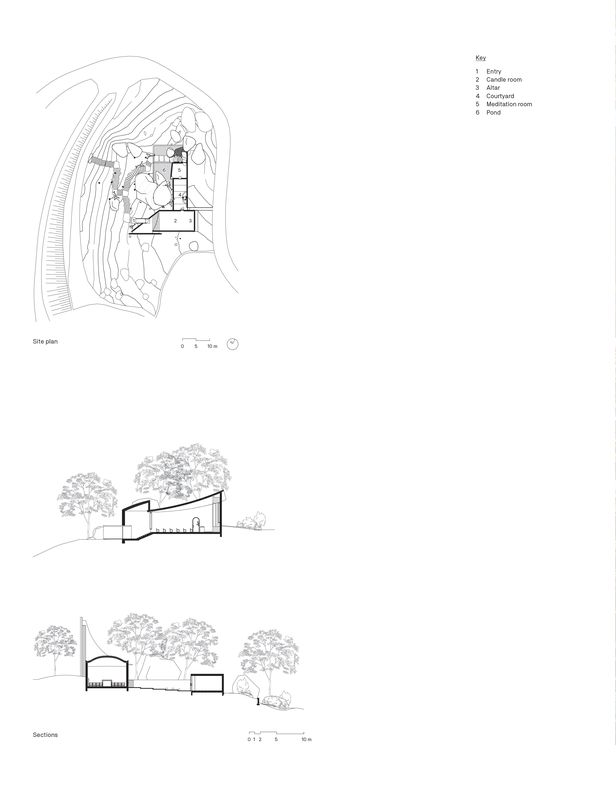

Minho, a region in the north of Portugal, is a place of rough beauty, where myriad shades of green run up the hills, dotted with watercourses and millennia-old boulders covered in moss and lichen. It’s feral and unpolished, a testament to the unwavering strength of everything that grew there before humankind came along. But humankind did come along, some five hundred thousand years ago, and has sought to dominate this fertile and wild place ever since. It is in Minho, not far from the place where Portugal was founded in 1143, that Australian-born, Bali-based architect Nicholas Burns has recently erected a chapel and a meditation room, the first in a number of commissions he is developing for the same client. “One of the initial intents was that it wasn’t a religious building, as such,” Burns tells me. “It started as a spiritual refuge; yet now it has a religious component to it.”

The project stands on a hill inside a thirty-hectare private estate, overlooking a denser urbanization down in the valley and the many green hills around it. When I visited with the architect on a recent Saturday morning, the air was crisp; a morning of humid and mysterious, fast-moving fog that enveloped rocks, trees and humans had given way to a soft sunlight piercing through the treetops. The resulting undulating light patterns swayed gently in the soft grass, and walking the rough-cut granite path up to the chapel awakened all your senses. For Burns, this was an important aspect of this place. He describes “sense of time”, “sense of seasons” and “sense of place” as “the elemental things that are important for people to feel naturally deeper within themselves, rather than an aesthetic that is more the rational response to experience.”

The chapel’s vertical scale takes an unexpected leap, shooting upward to the sky with its sinuous concrete roof.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The slithering promenade that Burns extends on the way to the building brings to mind similar exercises in different geographies, such as the pathway leading to Ryue Nishizawa’s incredible Teshima Art Museum in Japan. With the building tucked away between trees and gigantic granite boulders, the first thing that comes into view is a large concrete wall, peppered with circular markings that recall Tadao Ando – or is it Luis Barragán, and his wide free-standing slabs where the trees cast their shadows? But get closer, and the chapel shoots up into the sky, with a sinuous concrete roof rising up to a scale that feels completely out of place. The reason for this unexpected leap is made apparent once you cross the entrance threshold: an incredible baroque gilded wood altar caps the far end of the chapel’s main volume, its dimensions more fitting to a monumental basilica than a private chapel. It is an unbelievably ornate masterpiece of early eighteenth-century Portuguese religious art, property of the client and recently restored. “The shape of the roof was a direct result of the altar,” Burns tells me to describe the sweeping motions of the concrete above us. “It’s not something that I could’ve thought of in isolation.”

The chapel’s entrance, defined by a protruding corten steel chamber that resounds with the sound of your footsteps, opens up to a luminous vertical volume concealing the baptismal font in a nook. A flight of steps grants access to a second, darker horizontal volume capped by the altarpiece. The element dominates the space with its size and scale, dramatically illuminated by side openings as if to float. In this area, Burns reprised the vertical rhythm of the altarpiece’s turned wood columns to create an enfilade of stone candleholders that leads the eye to the baptismal font at the opposite end of the building, and designed a simple altar as well as the seating. The naked concrete surfaces that are so dominant in the exterior – and so unusual in these parts of the country – give way to limestone throughout the interior, including the floor and the walls, softening the space considerably. The silence inside is stunning, leaving out all the vibrant nature outside; but this contemplative setting is subtly disrupted by some of the elements in the space. The rough-cut stone of the altar, the rope in the chair seats, the way the candleholders hesitate between a round and a rectangular shape – these over-designed elements draw attention away from the space’s obvious central element. To the left of the altarpiece, a dark wooden door leads to a small paved courtyard and the other building in this ensemble: a meditation room.

A baroque gilded wood altarpiece caps the far end of the chapel’s main volume. An ornate masterpiece of early eighteenth-century Portuguese religious art, the recently restored altar informed the undulation of the chapel’s roof.

Image: Peter Bennetts

This second building is fundamentally different. Here, Burns evokes a more local and traditional use of stacked shale, which defines the courtyard walls and the meditation room volume in a much darker palette. “We deliberately made it a little bit rough,” Burns says, “more like a landscape wall rather than a building.” Inside, the space is clad in dark wood – ceiling, walls and floor – and once the door is closed, you are left alone with your thoughts. Light pours in through a vertical corner window, revealing a massive boulder outside that appears to float atop a tranquil pool. Here, the sounds of water and birds overlap to create a pleasing atmosphere, simpler and warmer than that of the chapel. The only reappearing element is the candleholders, in a line, which mirror those in the religious space. The candles, Burns tells me, were made out of beeswax by his son in Bali.

What to make of this ensemble, with its striking array of contrasts, its mix of architectural styles, its attempted grand gestures? Clearly, Burns is extremely ambitious: we see glimpses of Ando, Nishizawa, Barragán, but also nods to Le Corbusier in the swooping concrete roof of the chapel and the glass elements in the door, which bring to mind Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France. In contrast, the lower volume of the meditation room evokes more vernacular typologies: its horizontal orientation blends well with the surroundings in the same way that Peter Zumthor builds in Graubünden, Switzerland, or the early works by Álvaro Siza hide under the landscape. But where is Burns in the middle of all this effort? Perhaps because of the apparent lack of constraints, or possibly because of the private nature of the commission, the architect’s hand is lost and no clear intention emerges. And while Burns tells me, “The form of the building is not placed on the site, it’s derived from the site,” a study of the property is no replacement for a deeper study of place – which could have greatly benefited the end result.

Judiciously placed vertical windows connect the silent, contemplative internal spaces with the vibrant nature outside.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Minho, in the north of Portugal, is a region where other architects have intervened: Pritzker Architecture Prize-winners Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura, and even Siza’s master, Fernando Távora, have all worked with and within these geographies numerous times. Using a contextual approach, they succeeded in creating buildings that take advantage of the natural conditions, not seeking to overpower them, but yielding to them in order to thrive. This knowledge of the constraints is partly what has allowed them to create memorable works in the region; it is also a knowledge that I observe is absent in Burns’ Chapel and Meditation Room. While the architect seeks to innovate in the use and combination of materials – concrete, corten steel, shale, limestone, granite, wood – I question their appropriateness for this context, as their durability will be harshly tested. The ensemble atop the hill is the product of an ambitious set of intentions, their dissonant resolution in contrast to the harmonious nature around it.

Credits

- Project

- Chapel and Meditation Room

- Architect

-

Studio Nicholas Burns

- Project Team

- Nicholas Burns, Tiago Reis

- Consultants

-

Structural engineer

Projegui

- Site Details

-

Location

Minho,

Portugal

Site type Rural

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Religious

Source

Project

Published online: 13 Mar 2020

Words:

Vera Sacchetti

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2020