“Architecture is an act of producing a thing from a place,” wrote architect Kengo Kuma in the preface of his 2013 monograph, Kengo Kuma: Complete Works by Kenneth Frampton. Kuma established his practice in 1990 and his work now reaches far beyond the borders of his motherland, including a couple of upcoming projects in Australia. At the 2016 Regional Architecture Conference: Evoke, ArchitectureAU associate editor Linda Cheng sat down with Kuma to find out how the architect Frampton described as “quintessentially Japanese” creates places with local, regional flavour in an international context. And, in an age of “self-centred” architecture, as Kuma describes it, should architects be more “humble”?

Linda Cheng: There’s been quite a lot of talk at this conference about regionalism – as in Kenneth Frampton’s “critical regionalism” – I want to ask, what does regionalism mean to you and your work?

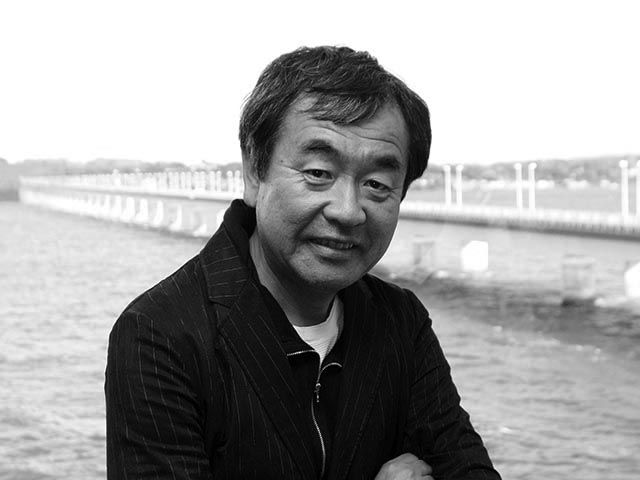

Kengo Kuma.

Image: Steve MacDougall

Kengo Kuma: I’m not interested in regionalism but I am interested in regions. Each region can give me different hints. I don’t like the word regionalism. It makes people misunderstand the value of the place.

I can have a special conversation with each region. It should be the mother of architectural design. Without the region, I cannot design anything.

That is the opposite attitude from the 20th century’s internationalism, which was fitting for the age of industrialization and the age of standardization. But in the 21st century, we should face each region and each community. That is the basis of our creation.

LC: You’ve done a lot of work in regional areas but also in cities. How do you maintain a sense of the region in an international city context?

KK: Everybody is moving globally much faster than before and communication, with the internet, is very international, but regions still exists. And the diversity of the region in such internationalism is not a contradiction.

The world is getting smaller and smaller but the region is becoming bigger and bigger. It’s a misunderstanding to say globalism killed regionalism. Globalism can lift up the value of regionalism. In that sense, there’s no conflict.

LC: How do you maintain a sense of the region in a global practice?

KK: I like to travel by myself a lot because each trip teaches me the differences of each region and my trips always include conversations with people (drinking with people sometimes) and that gives me a sense of each region. Without that kind of real experience, I cannot feel the region.

In that sense, the internet is an imperfect medium. What the internet can teach us is the value of the real experience. I still keep travelling and talking with people. Without that kind of real contact, I cannot design anything.

For every project, I start with a conversation with the people and feel the spirit of the place by myself. It’s always the beginning of the design process.

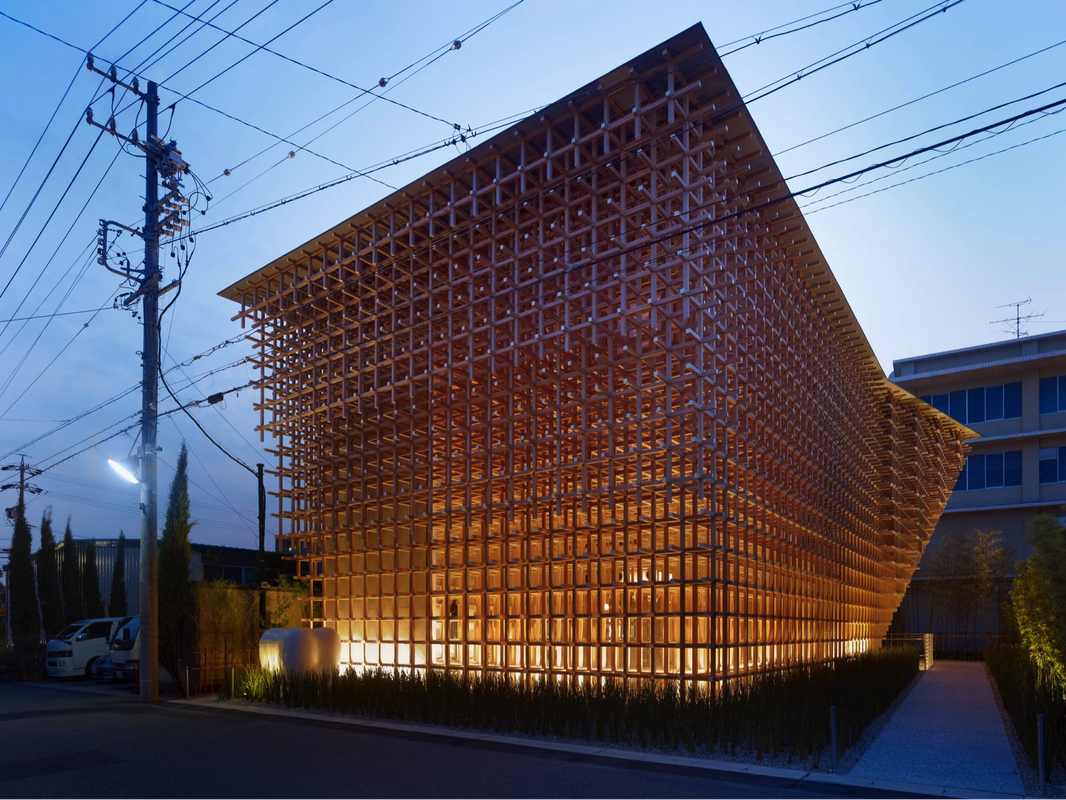

The Darling Exchange by Kengo Kuma and Associates and urban square by Aspect Studios.

LC: I’ve read that you begin all of your public lectures with your Water/Glass House, which near a house by Bruno Taut. You talked about the cultural exchange that happened there. How did this cultural exchange play out in your projects outside of Japan? For instance, Sydney’s Darling Square project, which is aptly named The Darling Exchange.

Sometimes a foreigner can find the value of the region. Sometimes people who have lived in the region for a long time forget the value of their own place. Bruno Taut is a very good example. He came to Japan and wrote a book about Japanese culture and history. That book is still very popular in Japan. And also Frank Lloyd Wright did the same thing. In that sense, the cultural exchange can enhance the value of the region.

Sydney is a very good example of cultural exchange. Take Jørn Utzon’s project the Sydney Opera House – his project in Sydney is better than his projects in Europe! He found the ideal location for his ideas. The shape of the yachts and ships is beautifully translated in that location.

My Darling Square project is also different from my former projects. I’d never tried that kind of shape before. The dynamics of the Sydney waterfront pushed me to go to that design. Also the very open atmosphere of Sydney pushed me to open the freedom of design. For me it’s a very important project.

Casalgrande Ceramic Cloud, Italy, by Kengo Kuma and Associates.

Image: Courtesy Kengo Kuma and Associates

LC: You write quite extensively. How does the process of writing influence your process of designing?

KK: For me, writing and designing are related, but they are different mediums. The designing process is actually not logical but intuitive. After the completion, I always begin to think, ‘what is the meaning of this project?’ That kind of thinking always comes afterward. In writing, I try to record that thought process. In writing, I can find the meaning of each project.

Without writing, the ambiguity is still ambiguous. Writing is a very necessary next step – design, write and then design again. It’s like climbing the stairs, step by step.

LC: I read that after you completed your first major commission, the M2 building (a Mazda car showroom in Tokyo), you wrote a piece of self-criticism. What prompted you to do that? And what did you learn from that process?

KK: That kind of feedback is necessary to go to the next step. I can change myself because of the criticism. Without being criticized, people cannot change themselves.

For architects, the most important thing is to change ourselves. Some architects never change and I don’t think that’s good. Take Picasso for instance, Picasso is always changing himself. We still can enjoy his work. Architecture is the same.

In that sense the car showroom is one of my most important projects.

LC: In 2008, you wrote a manifesto, Anti-Object, in which you criticized architecture that you described as “self-centred and coercive.” Today, you closed your lecture by saying, “We should go back to humbleness, warmness and kindness. That is theme of design in the 21st century.” With those two things together, do you think architects these days are too arrogant?

KK: [Laughs] Yes. The problem is architects are often used as a branding tool. So with a particular architect’s name, the value of the project can be raised. It’s a kind of misunderstanding architects have about the value of themselves.

Architects should be humble. The craftsman is basically very humble, because they know the limit of themselves. They’re working with a material and they’re informed by the material.

Architects should be the same. We should be humble in front of the material and that’s the basis of my work.