Ricky Ricardo: Why is it important to overview European landscape architecture?

Professor Lisa Diedrich.

Lisa Diedrich: Since the 1990s, or the end of the 1980s, design offices are not only working within their own countries or regions anymore. This is quite a new phenomenon and that’s why we thought it would be valuable to establish a platform of debate on a European level. Topos magazine started to do that in the early 1990s – it was the first platform of communication and exchange in European landscape architecture. However, when Topos moved from a European focus to an international focus, we thought it would still be interesting to consider this very confined geographical and cultural region that is Europe. As complicated as Europe is, it might be much easier for us to understand before we move on to wanting to understand the whole world, which is even more complex. That’s why in producing the Landscape Architecture Europe (LAE) book series we have to somehow be conscious of this particular “Europeanness” of landscape architecture production. This might change – it’s a globalized world and we don’t pretend that it will make sense forever to observe or comment on European landscape architecture, but for the moment we think it’s a valuable point of departure.

RR: In the prologue for In Touch (the latest in the LAE book series) you pose the question: “Is there such a thing as European landscape architecture?” Did you identify a common way of thinking?

LD: There will never be a final answer to that question, but answers are coming along with each edition. It may be that we will split up the question into less simplistic sub-questions that would reach further, but for now we’re still in an open phase of exploring.

RR: What would you say are the truly outstanding projects that have transformed the European landscape architecture profession in the past ten years?

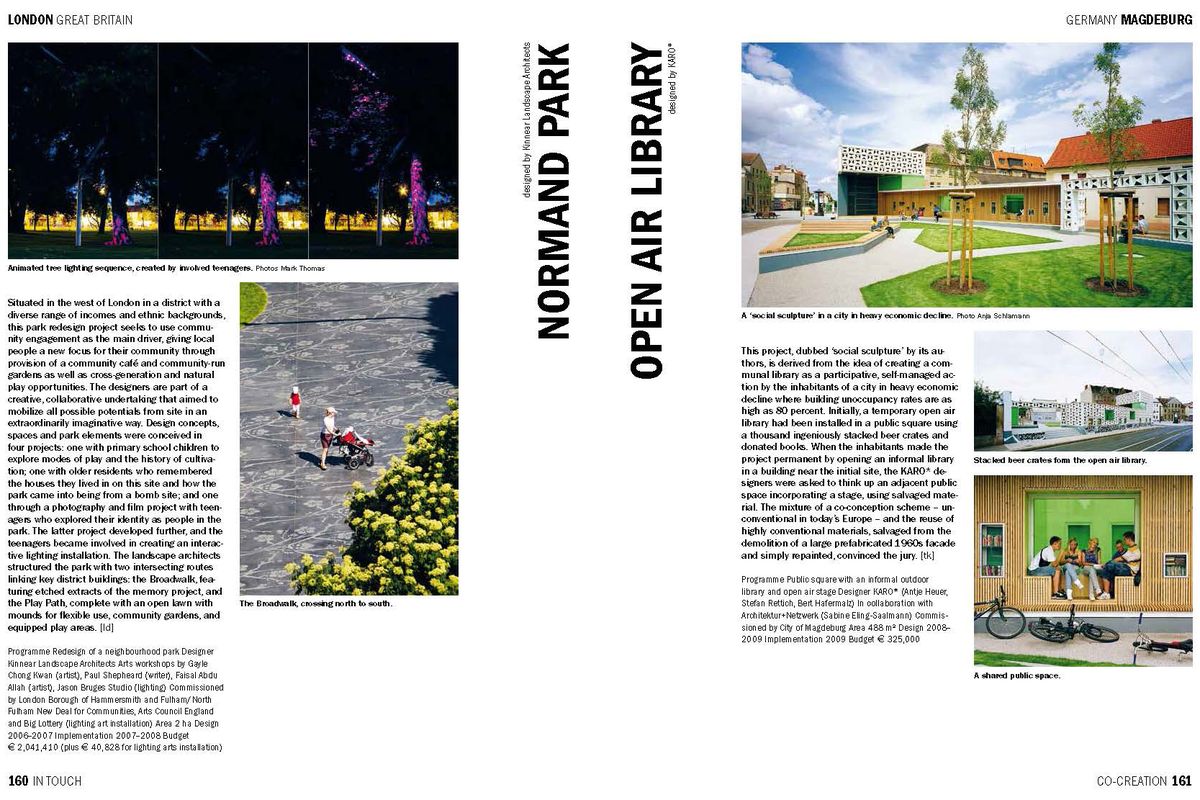

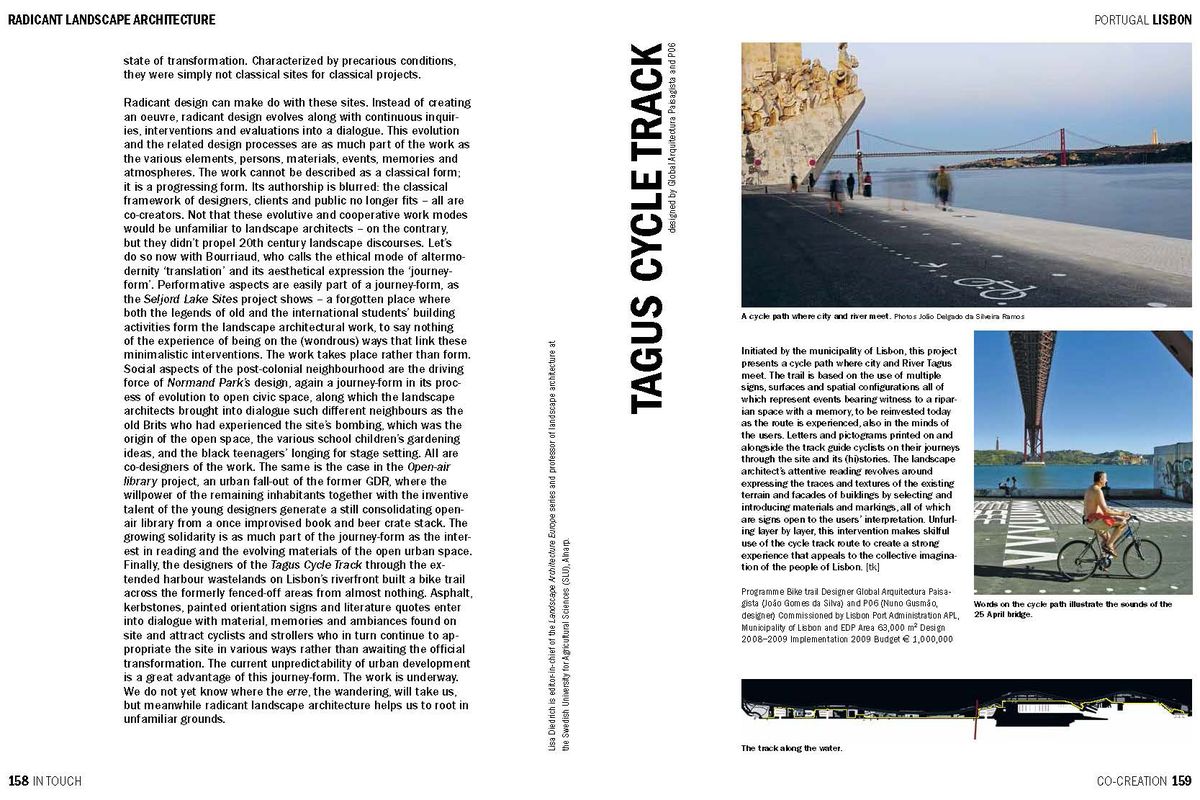

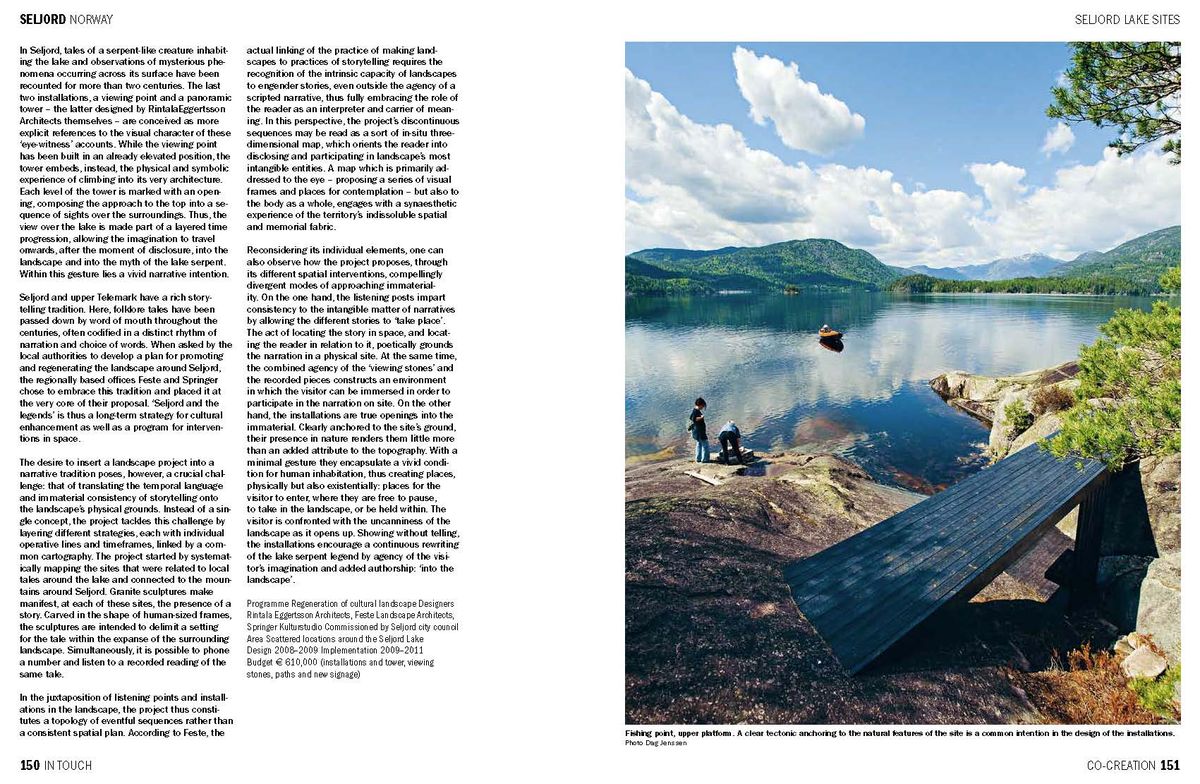

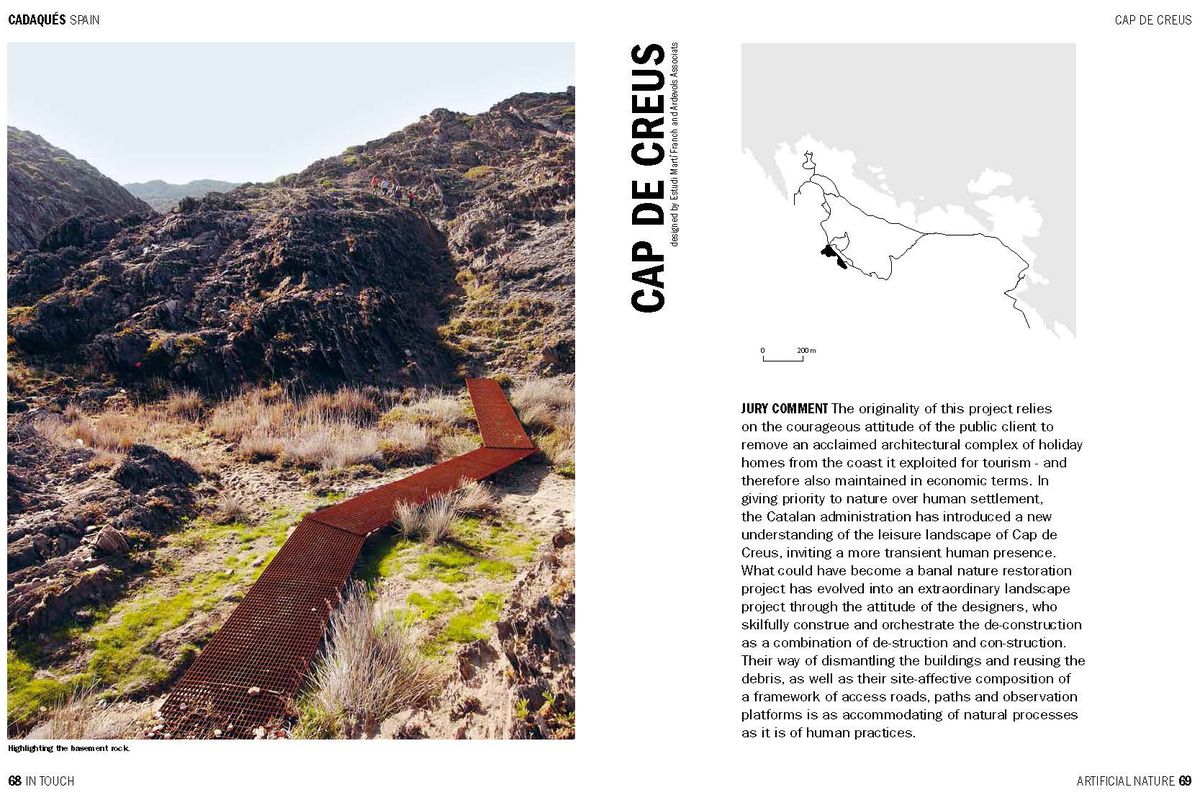

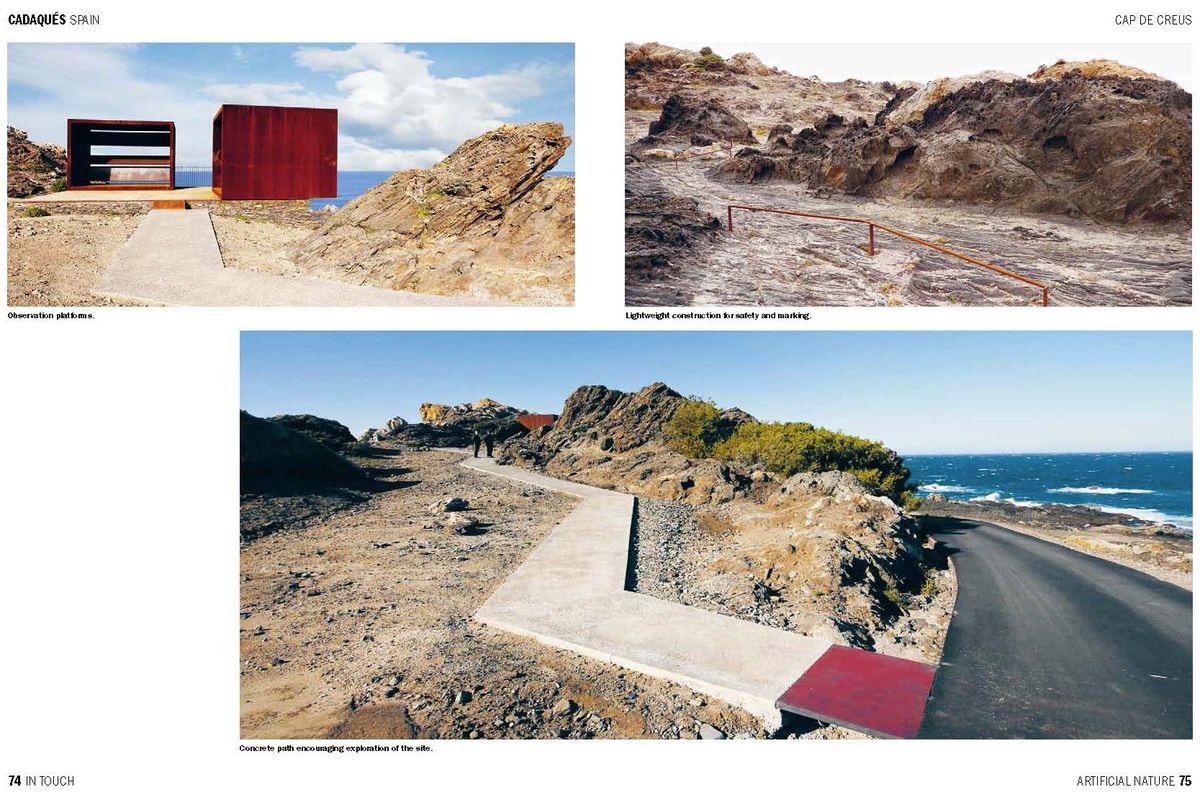

LD: We never really selected one project per book. The European Landscape Biennial in Barcelona, for example, hands out an award, the Rosa Barba European Landscape Prize, and they select only one project. So we leave that way of operating to them. For In Touch, we chose eleven projects that we believe to be outstanding and worth reporting on in depth. The projects I showed at the end of my public lecture here at RMIT could perhaps be described as transformative: Cap de Creus Natural Park in Catalonia, the Seljord Lake project in Norway, the Open Air Library in Magdeburg, Germany, and the river Tagus cycle track in Lisbon, Portugal. But they wouldn’t stand for the whole body of work.

Spread from In Touch, showing Cap de Crues by Estudi Marti Franch and Ardevols Associats.

Image: Courtesy Landscape Architecture Europe

RR: You mentioned in the prologue to In Touch that there’s an absence of projects from Eastern European countries, not because they didn’t submit, but because the work didn’t meet the jury’s quality standards. Why do you think that is? Is it for cultural, political or simply financial reasons?

LD: I think it’s just the political constellation of Europe and we can never put that aspect to the side completely. We receive entries from the Eastern European countries, but they speak very much to our jury (who are contemporary practitioners) of a traditional way of doing landscape architecture that the Western countries have moved on from. Western Europe produces much more forward-looking work, whereas what we often see from Eastern Europe is more of a decorative or gardening approach, or purely functionalistic infrastructure planning. Things that somehow tell you that they still have the mindset of the former communist regime. We now observe, and it’s an accent we want to give to the forthcoming issue, that there are emerging practices that are presenting a different image of Eastern Europe. So this time we are especially searching those countries and, we hope, capturing the first sparks of something new that is emerging there.

RR: I wanted to ask you about the value you see in designing abroad – for example, a Dutch firm completing a project in Greece, or operating outside of the environment that this particular practice is used to.

LD: I often reflect on this exchange of design knowledge from one country to another. Over the past two decades it’s been very valuable because, in the example you give, a thought that has been developed in the Netherlands could enrich the Greek understanding of landscape architecture and contemporary production. However, I’ve observed over the last few years that there has been less of an urge to transport new knowledge to other places. In this period of economic instability and the rise of democratic values, people want to discuss where they live and how it should be shaped more and more. It can cause problems if you simply import foreign designers to draw a nice competition entry, a slick masterplan, and then hand it over, ask those guys in Greece to build it; that doesn’t work anymore. So I think we have to re-evaluate that practice.

Europan Europe, a competition for young architects created in the 1980s, has exactly that agenda, to import foreign knowledge to a place where it hasn’t existed before. Europan is in a crisis, because the entries they receive today don’t correspond with the requirements of the particular place, so they feel uncomfortable with so much distant work, and you could say that Europan is a mirror of the discourse in general. People are starting to ask if there should be a shift in method: how can we encourage designers to work more site-specifically, even if they are foreigners? How can we establish collaboration between, for example, Greece and the Netherlands, to come together and produce work that’s more site-specific and develop more site-specificity over time? It’s the post-masterplan epoch (laughs).

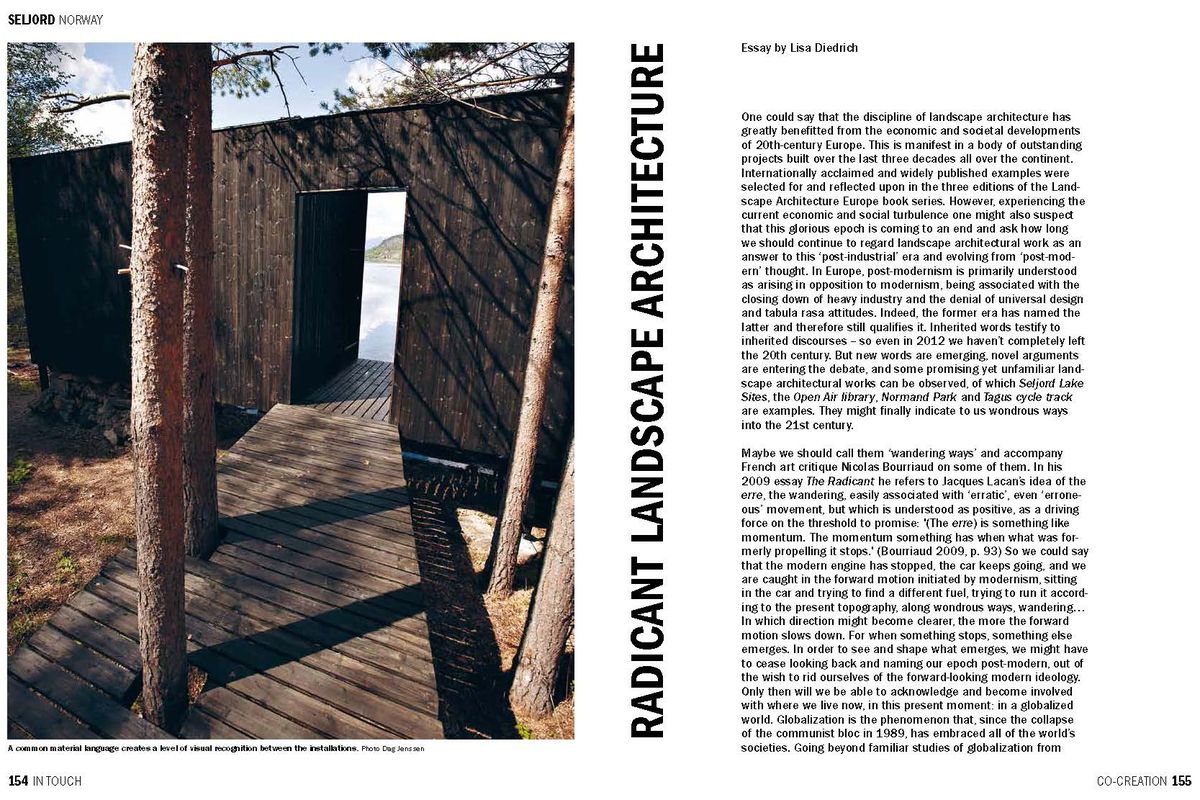

RR: Could you talk about the title of your public lecture “Radicant – European landscape architecture” and the idea of taking root in unfamiliar grounds. Do you see this as a valuable metaphor for the future of landscape architecture?

LD: The title is borrowed from the book The Radicant by Nicolas Bourriaud. It’s a given condition that people are moving and thought is moving, so this idea can be condensed into the figure of the Radicant. Bourriaud puts forward this metaphor from the vegetable realm. Immigrants, urban wanderers, nomads and exiles, they all come from somewhere and they want to go elsewhere. They somehow need to put down roots but not in the way we are used to from former eras, where we just dwelled in a single place, before the world became globalized. Everybody grew, like a palm tree, deep down into the ground. Today our roots are probably still existent but they would grow secondary roots from the stem and move onward, like the ivy which grows by developing its relationship with the wall. I believe this to be a useful metaphor for designers and design work.

RR: It relates to the concept of entropy in design, doesn’t it?

LD: Well, that’s probably in it and the whole post-structural philosophy of the end of the twentieth century is there too. But the strength of Bourriaud is to formulate this in a quite comprehensible way, not as abstract as Gilles Deleuze or any of those French philosophers. Bourriaud somehow puts it into a metaphor, which is useful in the face of that very stretchy thought, “What’s going on in our design world?” Design is not static. You don’t just draw the masterplan and create the pictures to hand over to the client. We could probably deliver more design works that would be “in the flow” (occur over time). There would be an initial idea and then we would work with stakeholders and other designers maybe, whoever is an agent on site, and we could develop that work to become more of “a flow of work” and not so much “a figure of work.” It could be more akin to a film than a masterplan (laughs) or the storyboard of a film, you know, something that aims at movement and not so much at a static state of things.

Professor Lisa Diedrich was in Melbourne in 2013 to attend the doctoral examinations of RMIT PhD candidates Kate Cullity, Perry Lethlean and Anton James and deliver the public lecture: Radicant – European landscape architecture at RMIT.