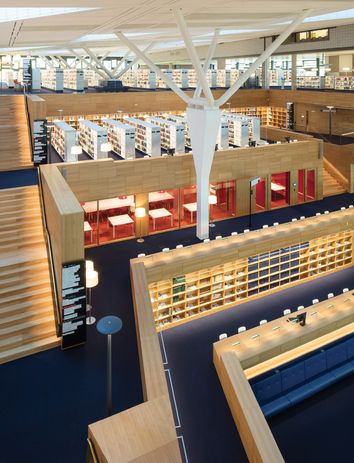

The new national library of Luxembourg is a complex and multifaceted structure where the deftness of the architect’s illustrative hand has resulted in a flowing sequence of spaces that beckons the community.

As a student of architecture in the 1970s, I remember being astonished by a set of design competition drawings with amazing atmospherics, seductive material sensibilities, and a sense of programmatic mystery and uncanny juxtapositions. The images were all the more impactful as they were the work of a student architect – an Australian studying in London at the Architectural Association: the young Peter Wilson. Here was an unmistakable talent.

The images were for Water House (1976), which remains a refreshingly provocative and alluring project. In some ways, it provides the initiating bookend to an increasingly expansive portfolio that defines the German–Australian practice that is Bolles and Wilson. I describe these drawings and design as a “bookend” not just on the basis of chronology, but also because the role of the drawing, the hand sketch, the impressionistic view, has remained ever-present in the work of Bolles and Wilson, no matter the scale, complexity or program of the project.

The massive branching central columns that begin at ground level transform, in “a magical moment,” into seating at the top of the library.

Image: Christian Richters

It was the presence of a series of perspective views scattered around the worksite of the Bibliothèque Nationale de Luxembourg (BnL) during a visit one year ago that rekindled for me an appreciation of how the architectural thought of Peter Wilson is embedded in the sketch. As I was guided through the interior of the project, then under construction, we kept arriving at workstations (nothing to do with computers – just large wooden tables overflowing with sets of construction drawings and folios of details). Close to each workstation was stuck a Peter Wilson drawing. Each drawing projected the particular viewpoint as a single image.

These delicately coloured vignettes were not photorealistic renderings produced through massive computer cycles and hours of photoshop finesse; rather, they were a few black edges and outlines, with thin-line patterns, material details and patches of colour and accents. Deceptively simple and seductively believable, these images had been placed around the building in advance of a visit by Luxembourg’s Minister for Culture some months before, to provide visual referencing of proposed spatial qualities. The many and diverse trades working on site had found the drawings immensely useful in understanding the architectural intent of the project – and so they had remained on display. Beyond the innumerable, highly detailed printed drawings, the manipulable 3D models and the screen after screen of Revit-controlled overlays and specifications, it was these singular views that verified where the work was all leading.

The BnL project followed a complicated and extended gestation and completion period that commenced in 2003 as part of a design competition in the Kirchberg precinct, at the western end of Avenue John F. Kennedy, to convert the European Parliament building into the new library. The project stalled in this location, as the necessary shifting of European bureaucrats was delayed again and again. Although preliminary design work was completed at the original site, a new mandate was established for the BnL in 2013, repositioning it in a new location at the eastern end of Avenue JFK.

The new site allowed for a revised formulation of the library and its surrounding context. Now facing south-east, more directly in contact with Avenue JFK and the new tram line and tram stop that provide easy linkage, the BnL and its massing also negotiates the elevated plateau of Parc Réimerwee, which rises behind the project site. Part of a highly differentiated but fairly regimented procession of institutional and commercial blocks on the north side of Avenue JFK, the BnL faces across this major thoroughfare, where the landscape steps downwards to the south.

Bolles and Wilson’s characteristic attention to material surfaces is evident in the red pigments and varied surface textures used on the exterior precast concrete panels.

Image: Christian Richters

The current history of Bolles and Wilson is not only bookended by the fundamental role of the sketch in their design practice, but also by the project of the library. Both students at the Architectural Association in the 1970s, Julia Bolles and Peter Wilson formed their practice in London. However, it was winning the 1987 design competition for the Münster City Library (completed 1993) that set theirs up as an influential contemporary architectural practice. The City Library in Helmond and the unrealized BEIC (Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura) in Milan join a prison library in Münster and a proposal for the Strasbourg University Library to form a broad corpus of work in this typology. Although the Münster City Library and the BnL contrast vastly in scale, civic and cultural role and complexity of operations, both reaffirm that for all the talk of a purely digital future, the physical library of books, artefacts and print remains a vital social, civic and intellectual centre for a city (and a nation).

The BnL is a complex, multifaceted building that operates as the repository of all publications produced in Luxembourg. As the national library, it holds particular responsibilities for the cataloguing and safekeeping of publications, documents and various media of national and international importance. These responsibilities produce a building that consists of an ensemble of public functions and accessible spaces embedded in a large-scale repository and storage facility.

The long north–south cross-section reveals this superimposed condition, with a continuous flow of public space sequenced from the south. The two-level entry foyer transforms into a grand four-level volume that subsequently terraces upwards to a series of meeting rooms, publicly accessible stacks and reading levels, before the final single-level public stacks and reading space extends to the north. A collection of meeting and conference rooms sits above the main entry and foyer, creating a slight compression downward upon entry. The large, upper-level reading area rests above a massive five-level archive and storage complex. Forming the largest bulk of the project, this complex is a distinct and autonomous section within the assemblage.

Among the white walls and wooden trimmings that dominate the interior are splashes of colour, like a red reading room where visitors can review old or rare publications.

Image: Christian Richters

The composite spatial flow, as experienced by the public, moves from south to north, from street frontality to an elevated garden platform facing the adjacent escarpment of Parc Réimerwee; from a high vertical volume to the upper-level horizontal spread, this time compressed upwards from storage mass below. This central cascade is flanked to the east by public study and meeting rooms, while library and administrative offices dominate the western flank.

It is the figural identity and formal transformation of the massive central columns that grabs the eye, eventually delivering a disjunctive reinforcement of these phases of spatial expansion and compression. Beyond the double-height foyer, the central volume expands downwards and upwards, and the ceiling is supported by a single column that morphs from a relatively small, square base into a broad, almost linear, inverted triangular cap. Two sets of tubular steel supports sit upon this cap, tilting outwards from the column line in two directions to extend the bracing function to the roof trusses. The next column along to the north repeats this form, only now it is partially buried in the next floor level.

From this point, the tubular supports become the same; yet totally different. Now, their column base is completely embedded in the upper-level floor above the storage mass. What were the tops of the columns and support cap have become the seating and benches within the stacks and desks of the public reading zones. Structural components that, from the entry level, looked thin and barely supportive are now at head height, massive in their diameters and impressive in their pure material scale. This re-experiencing of a singular object that conveys powerfully different sensibilities is a magical moment beyond the functional imperative of a large open-span ceiling.

The library’s variety of public spaces has already made it a valued community centre, used by school and other local groups as well as politicians and bureaucrats.

Image: Christian Richters

As with most (if not all) Bolles and Wilson buildings, considerable attention is given to material surfaces at BnL, with variegated colours throughout – exuberant but judicious. And nowhere more so than the external facades, where precast concrete panels are coloured in red pigments, with different surface textures and treatments circumventing any sense of homogeneity or factory standardization.

The BnL was, for Bolles and Wilson, a sixteen-year marathon, split into two phases on two different sites. Even at the time of writing, more than a month after its opening, the building is still being “installed,” with books and archives needing time to acclimatize and the space itself learning how to handle its massive inventory. Peter Wilson recently related that, already, the library has become a centre for not just bibliophiles and researchers, but for locals, school groups, community meetings and reading clubs, as well as the politicians and bureaucrats that partially define Luxembourg City.

If Münster City Library launched the architectural practice of Bolles and Wilson, the BnL will expand the reputation of the practice, already recognized for producing mature architecture, remaining fresh and inventive, and extending a character and sensibility that is responsive and specific. The surety and deftness of Peter Wilson’s illustrative hand is now confirmed in the spaces and surfaces of the library. Both the drawings and the building convey this continuing, unmistakable talent.

Credits

- Project

- Luxembourg National Library

- Architect

- Bolles + Wilson

Germany

- Project Team

- Julia Bolles-Wilson, Peter Wilson, Heiko Kampherbeek, Axel Kempers, Manfred Kieler

- Signage

-

L2M3 Kommunikationsdesign

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

Akustik- Ingenieurbüro Moll

Building services Felgen and Associ é s Engineering

Energy systems EBP

Fire protection HHP Berlin

Structural engineer Schroeder and Associ é s

- Site Details

-

Location

Luxembourg City,

Luxembourg

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2019

Category Public / cultural

Type Libraries

Source

Project

Published online: 21 Apr 2020

Words:

Donald Bates

Images:

Christian Richters

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2020