A grassroots revolution is happening in architecture – a move away from the “starchitect” model of showpieces and toward a more thoughtful approach that embraces people and landscape as central, not incidental.

Sydney’s Panov Scott Architects is part of the movement. Directors Anita Panov and Andrew Scott live and work in a terrace house in Sydney’s Paddington, a light- and plant-filled space that they share with their two young sons and (Monday to Friday) three colleagues. In the front two rooms, communal tables are flanked by bookshelves ceiling high. The serenity of the space reflects the growing body of “transformations” by the practice, which was awarded the Emerging Architect Prize in the Australian Institute of Architects’ 2016 NSW Architecture Awards. For Anita and Andrew, home and studio are their centre of gravity and a collaborative place for creating and learning.

The couple met while studying architecture at the University of Newcastle. On an exchange trip to Brussels, they realized that travel, and each other, would be lifelong teachers and companions. In different ways, their childhoods had taught them to live frugally, to work hard and ask simple but profound questions such as, “What is a house,” and “How little do we need to live well?”

At Armature for a Window (2012), a vertically sliding glass wall opens the house to the garden.

Image: Brett Boardman

“An idea we latched onto early was something Cicero said: A house is like a library and a garden, and when you have a library and a garden, you have all you need,” explains Anita. “That’s what we’ve always aspired to in how we live, and how we design for other people. [Living] smaller is the other thing – we all need less than we think.”

Anita and Andrew served their apprenticeships at larger, lauded firms (she with Smart Design Studio and he with Candalepas Associates) before founding Panov Scott in 2012 with three golden rules. “One: Projects have to be a place for our client to live/work/be – transformations, not speculations. Two: We stay involved from start to finish. Three: Our clients are good people; you go on quite a journey together.”

With each transformation, Panov Scott breathes ethereal light into dark corners and connects even the most incidental of spaces joyously to a garden. Key to each has been the window – which, in Panov Scott’s architecture, is heroic. Each project idiosyncratically uses thresholds between inside and out to expand the ways of living in a house.

Their first project, Armature for a Window, was Andrew and Anita’s own semi-detached terrace house, a testing ground for ideas and for how they might work together in practice. A small sash window in the front room inspired the vast, vertically sliding glass wall that opens the rear of the house to the garden. “As we sat beside it for months, talking and planning, that small window took on mythical proportions. Its action and detail became synonymous with light and air. The house itself little more than an armature,” explains Andrew.

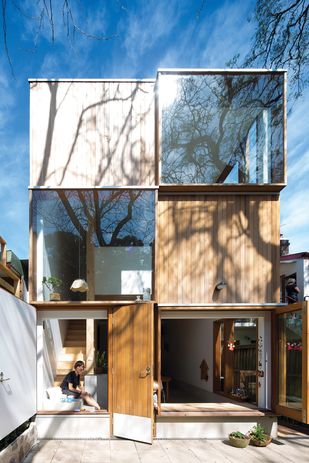

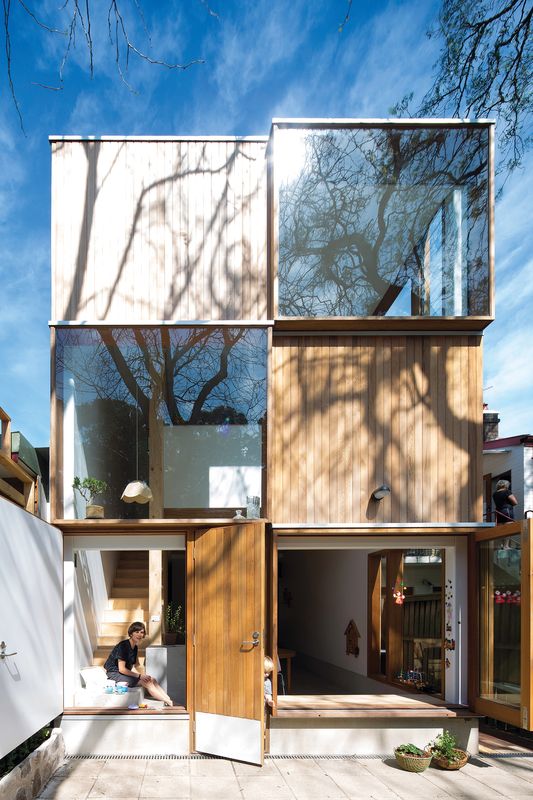

Three by Two House (2014) in Sydney’s inner west is framed with a chequerboard of six window panels in timber or glass.

Image: Brett Boardman

In Three by Two House, a semi-detached dwelling in Sydney’s inner west, a small opening twists skyward at the nexus of the retained original and reconfigured sections. This allows light down into the centre of the long plan, where it washes over a splayed plywood panel signalling a brighter room beyond. The room expands in height to six metres, framed with a chequerboard of six window panels in timber or glass. Instead of creating a dedicated lounge, the architects activated the threshold edges of the communal dining and kitchen with dual-purpose elements: an east-facing alcove window looking into a tiny courtyard, and an elongated concrete stair landing that doubles as a sunlit platform for play.

So if you lose the “lounge room,” how do you define a house? “We taught a design studio (at the University of Technology, Sydney) on that very question,” says Andrew. “You reduce down to the core functions required of a home – a place to sleep, a washbasin, a kitchen, somewhere to read – and build an idea of domestic environments through these small human actions and armatures.”

Bolt Hole, in Sydney’s inner east, turns a two-bedroom cottage into a courtyard house, with no increase in size. On a site of just 120 square metres, Panov Scott pushed the built form to the perimeter, externalizing the core of the house as a central light well and courtyard, around which pivots seventy-five square metres of internal space. Services, storage and a study are sleeved into the perimeter. Bedrooms and the bathroom were moved from the front to the private rear, while the kitchen and living rooms were moved up to the laneway edge. Entry is from the centre, so arrival is at the courtyard, where a Japanese maple tree thrives and the old fireplace is restored as a relic.

In Sydney’s inner east, Bolt Hole (2018) skirts the perimeter of a 120-square-metre site.

Image: Murray Fredericks

“If a house can have a centre of gravity, here it is the garden court – a small, intensely planned space that brings amenity and delight to every room,” Anita says. Socially, however, the hub is the kitchen, where it’s possible to engage with the lane, the courtyard and each of the private interior spaces.

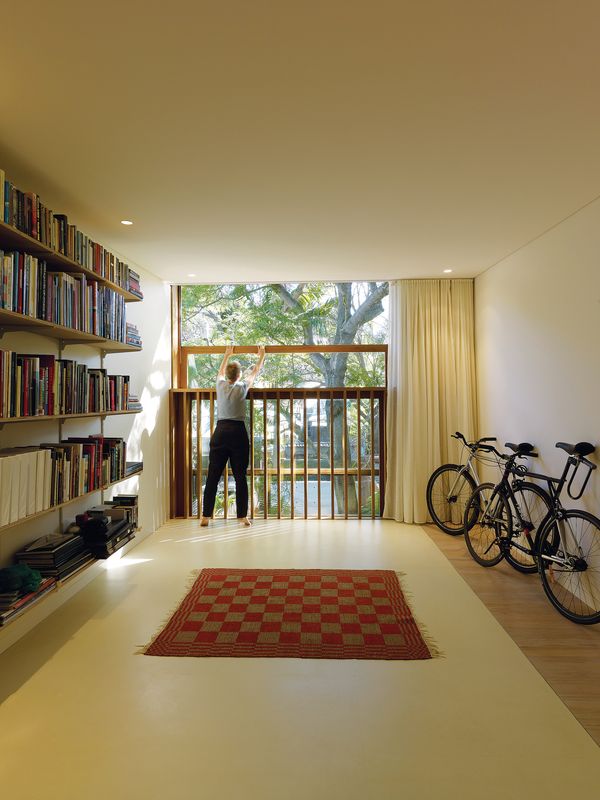

Jac House, in Sydney’s inner west, celebrates the seasons in a love letter to a jacaranda tree. Between a Federation cottage and the older, sculptural tree, Panov Scott inserted a new volume, open to the garden at ground level, with a second storey sweeping up toward the tree’s outstretched limbs. “Our transformation mediates. It’s literally neither open nor closed, not dark, or so bright. At each moment in time, a part of the house is optimally refined for the hour, the season, or the mood,” explains Andrew.

Their material palette is finely crafted, evoking memory, inviting patina. Silvering timbers, recycled bricks, liquid concrete descending stairs and wrapping up walls to mark a datum. Sometimes a single material anchors a project, like Armature’s gently ageing, coved cedar frames, inspired by the traditional timber houses of Kyoto, or Bolt Hole’s black-speckled sandstock bricks – a thrilling contrast to the interior’s precision.

Jac House (2017) celebrates the seasons in a love letter to a jacaranda tree.

Image: Brett Boardman

In 2017 the pair held A Small Exhibition in Sydney, gathering twenty projects by like-minded local practices, each bringing radical new amenity to homes on a tiny footprint. “We curated the exhibition as a body of research on small housing,” says Anita. “From that came an invitation [by New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment] to work on a state-wide small housing design guide.”

Other public projects have followed, including the revitalization of the Museum of the Riverina in Wagga Wagga and the renewal of the community centre and change rooms for Bronte Ocean Pool Swim Clubs in Sydney’s east.

Is it difficult moving between small-scale transformations and public projects? “The design thinking required of small projects is transferable from the private to the public domain,” says Andrew. “We are, after all, making spaces for people. Architecture is background, not foreground, or as architect Florian Beigel said: it’s the rug, not the picnic.” Cicero might approve the metaphor. panovscott.com.au

Source

People

Published online: 23 Jul 2019

Words:

Peter Salhani

Images:

Brett Boardman,

Murray Fredericks

Issue

Houses, April 2019