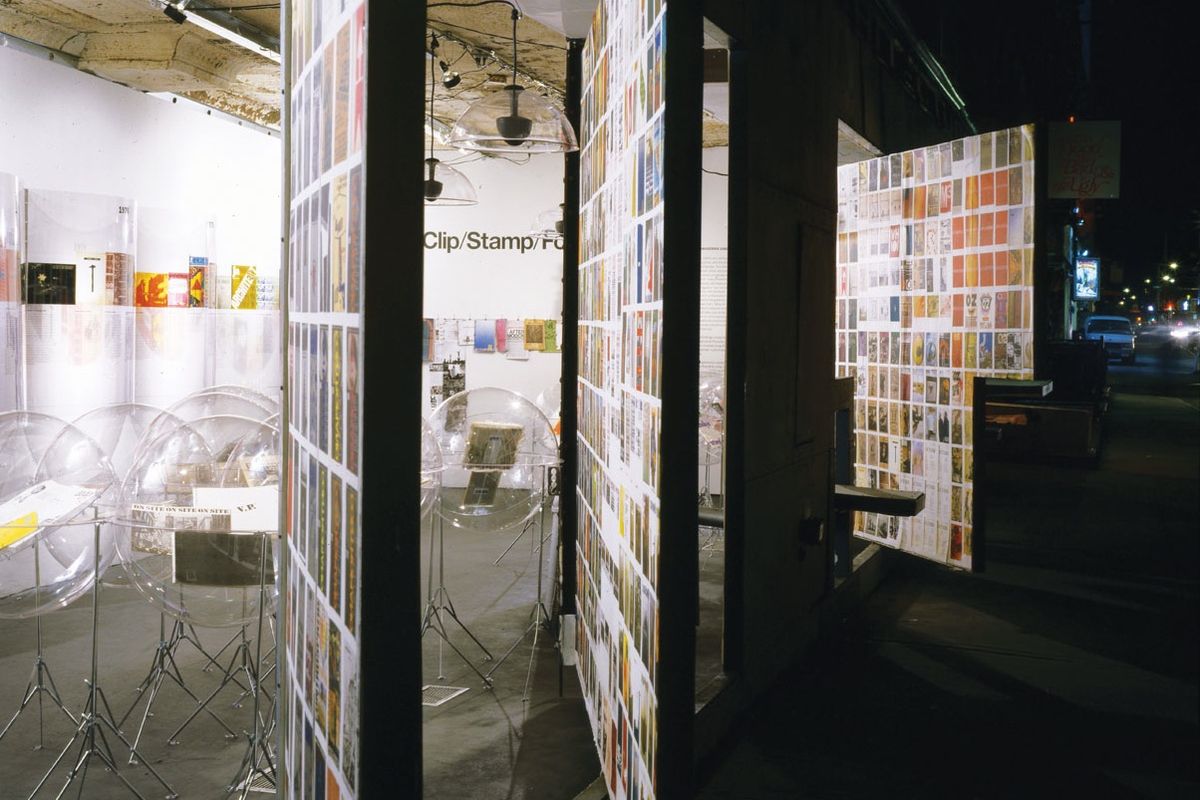

Nicole Kalms: In the introduction to [the exhibition] Clip/Stamp/Fold you state that “the proliferation of new technologies of communication and reproduction had an enormous role in defining historical and contemporary avant-garde practices.” How do you think current communication technologies are defining contemporary practices?

Beatriz Colomina.

Image: Job Jansen

Beatriz Colomina: Well, that’s always very difficult to say. It’s easier to go back in history and see what actually happened. It is impossible to think about the avant-garde – not just in art, but in literature, in architecture, etc. – without thinking about its engagement with the media. For example, [the movement] futurism didn’t really exist – not even the group of artists existed, and no work [existed] whatsoever – before the publication of the The Futurist Manifesto in the pages of the most important newspaper in Paris, Le Figaro, a newspaper that was revered in Europe. If the manifesto had been published in a local Italian newspaper, futurism would not have gone anywhere. But in Paris it had a transformative effect. It not only advertised something that didn’t quite exist, but it recruited members of the group to join this not-yet-existing movement. The newspaper made the project happen.

You can go through all different avant-garde movements [and see a similar pattern]. Surrealism, for example, didn’t exist outside its multiple publications (La Révolution surréaliste, Documents, Minotaure, Marie, etc.) Architect Le Corbusier didn’t exist – not even his name existed – before L’Esprit Nouveau. These architects, artists and movements are basically an effect of the media, of their own publications … Now, in the last two decades at least, we have obviously experienced a revolution of at least the same significance as the one that brought us photography, film, illustrated magazines and modern publicity. The internet, email, blogs, Google, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way we work, write, analyse, interact, play and even make love. Can we expect architecture not to be affected?

I am sure there are things out there already happening in architecture and we are unable to see them yet. It is somehow easier to see it in other fields. Think of that young woman in Baghdad who during the occupation started writing a blog called Baghdad Burning about her experiences and the experiences of her family living in the city. This blog all of a sudden had hundreds of thousands of followers – millions, perhaps. And it continued for three years before her family moved to Syria in exasperation. Since then, departments of literature have started analysing the writing. It is recognized as a new genre. And, symptomatically, old media is absorbing new media. A book based on the blog was published and it won several journalism and literature awards. I suppose in architecture we are also at the very beginning of something, and presumably in years to come somebody will be saying, “Look at the way these people were using new media to change the field.” But for us it is probably still too hard to see.

Ari Seligmann: Taking into consideration the little magazines of the 1960s and 1970s, the recent evolution of the book – for example, big books such as S,M,L,XL [Rem Koolhaas and Brue Mau] and the Event-Cities series [Bernard Tschumi] in the 1990s – and the rise of hybrids like Artifice or ACTAR’s “boogazines” [book/magazine hybrids], are the changes in print media changing the sites for architectural production?

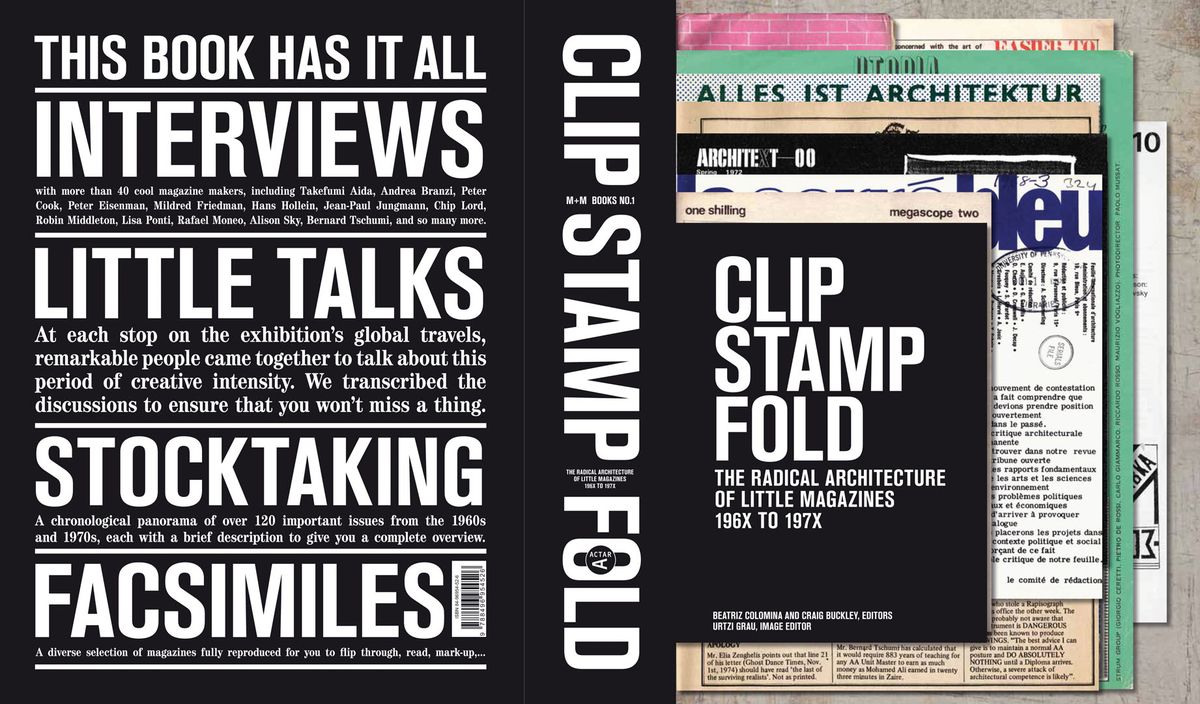

BC: It is interesting that at the beginning of the twentieth century the dominant medium for avant-garde groups was the little publication. There were professional big magazines too, such as L’architecture vivante, Casabella, L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, etc., but the ones we remember, the ones that the museums of modern art collect, the ones that changed the way we think about architecture, were little magazines. Magazines such as G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung, L’Esprit Nouveau, De Stijl, Mécano, Das Andere, Red, Blok, i-10 and so many others. These magazines become, in some ways, more permanent than buildings. And of course there were books too but, interestingly, many of them were dependent on the little magazines. For example, the famous books of Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Urbanisme, L’art décoratif d’aujourd’hui, etc., perhaps the most influential books of the century, were simply collections of articles first published in L’Esprit nouveau. Closer to our times, Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture is also a little book that changed the way we think about architecture, and again, it’s a book that came out of articles previously published in architectural magazines. Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York and Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City are also manifesto books driven by a polemical impulse.

You are correct – in more contemporary times there has been a kind of trend towards the monumentalization of the book. Books have become doorstoppers recently. Even my own Clip/Stamp/Fold is big. It is the book as a kind of archive, perhaps. Where we are going with that I’m not sure. Printed media … tries to absorb new media. New media doesn’t kill old media – television didn’t kill film, and the internet didn’t kill television – but it transforms it. As Marshall McLuhan put it, new media makes us aware of old media. It’s precisely because we are in a new age of communication that we’ve become fascinated with how the old media, the little magazines, operated. For the first time, we are actually able to see them with this kind of distance and attraction.

NK: In Clip/Stamp/Fold you note that the proliferation of little magazines corresponded with shrinking job prospects. There was time to write and reflect, and the magazines became the site for architecture production. Do you think that the continued reverberations of the recent financial crisis mean that architects will again start thinking and writing reflectively?

BC: Yes. I’m actually quite optimistic because if you look at it historically, the moments of more intense architecture innovation tend to correspond with moments of slowdown in the economy. After the proliferation of not-very-interesting iconic architecture in the years of the big boom, you can look forward – in fact something is already starting to happen – to a more careful thinking and reflection in our field. These slowdown moments are opportunities for the incubation of new ideas and new ways of operating. How that will develop, I don’t know. It is clear, in retrospect, that in the early decades of the twentieth century, and again in the 1960s and 1970s, little magazines were the sites of extraordinary innovation. So where is this energy going now that the printed page is not necessarily the dominant medium? Is there a new generation of architects operating in new media and are we still unable to see them? It’s very possible. Other younger people will notice them before I do.

AS: Is it your sense that many contemporary magazines are less radical?

BC: No question about it. I mean, can you compare any of the new magazines to what we saw in the Clip/Stamp/Fold exhibition?

AS: Is that because there is less at stake, or the producers think there is less at stake?

BC: I don’t know why it is. They try hard – maybe too hard. The little magazines were driven by the big issues and transformations of the day, but at another level they were just the attempts of isolated people to connect themselves to a bigger world. They were just trying to project something and they discovered themselves in doing so. They were the sites where the new Mies van der Rohe constructed himself, or the new Archigram, or all these people that we had no idea about until the magazine came out. Archigram, by the way, is another example of a group of architects that didn’t exist before the magazine.

AS: Do you think the role of the critic has changed in the new media environment?

BC: Oh, yeah.

AS: And how. It seems like the professional journals continue and the volume of critical journals also keeps getting …

BC: … smaller, actually.

AS: Yes, if you think back to Assemblage and others …

BC: Well, we do not have Assemblage anymore, but we have Grey Room and we have Log and what I will call text-oriented journals that are quite theoretical and quite serious, and they are contributing a lot to current debates. So this line of little theoretical magazines has not ended. And most of what happens in blogs and so forth is not very critical. The emphasis is on selection and association of material, comments. Instead of sustained commentary, you have short opinions, personal reactions. So these older formats of magazine have a function to sustain criticism while the blogs sort out some new strategies for analysis, which I do think will happen. So today there is a different role for the critic, I suppose.

NK: Do you think that that’s one of the negative effects of the hyper media state that we are in?

BC: Yes. But only in the sense that I am impatient, waiting for the new angles of new media. There is too much writing that still lacks content. The critical view is not there. You expect it to be, because this is a media free of the usual financial, technical and censorship restraints, but it is there very rarely. I’m a bit schizophrenic in expressing my disappointment because I think something will emerge that will be super interesting and important. With every type of new media there is always a complaint. With the emergence of the professional magazines there were always the people that complained that architecture now was being designed so it would look good in magazines, that we have lost something. Each new medium brings the story about the loss of something. But then you look back historically and you see there wouldn’t have been Mies without all these publications. When you look at the houses he was building for real clients – Mosler House, Eichstädt House – at the same time as he was doing the most extraordinary projects in magazines, like the glass skyscrapers, or the brick and concrete houses, which are really paper architecture, you realize that the real revolution happened in the media. Likewise, and closer to our times, you can talk about a whole generation of architects such as Peter Eisenman or Rem Koolhaas who were able to do so much in the media before they were able to do anything on a construction site. And then, with so many of the architects we cherish, you may ask yourself what their real contribution to architectural culture is. Is it the buildings or their ideas about buildings? I think the media has been actually a very positive force in architecture. In fact, we wouldn’t have a concept of architecture without it. No books, no architecture. Architecture is the intersection of ideas and buildings. You simply cannot have one without the other.

Source

People

Published online: 16 Apr 2013

Words:

Niki Kalms,

Ari Seligmann

Images:

Storefront for Art and Architecture

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2013