The Perth Arena is the first building to be completed in the Perth City Link project, a plan to sink the Perth–Fremantle railway line in order to better connect the central business district with the adjacent Northbridge entertainment district. The Link project is anchored by a rejuvenated central Perth railway station to the east and the Perth Arena to the west, with the space between to be filled by a ribbon of mixed-use, high-rise buildings replacing the now submerged railway, the to-be-relocated Wellington Street Bus Station and the recently demolished Perth Entertainment Centre. Construction on the multipurpose venue commenced in June 2007 and it officially opened on 10 November 2012. The venue seats 15,500 for concerts and slightly fewer for sporting events, making it comparable in size to Madison Square Garden.

Perth Arena is an essay in very big ideas and a very local context, like all ARM Architecture projects, such as its National Museum of Australia (NMA). John Macarthur, writing in Architecture Australia (“Australian Baroque,” vol 90 no 2, Mar/Apr 2001, 48–61), likened NMA to Borromini’s S. Ivo della Sapienza in its baroque sense of movement never ending, without closure, and the creation of a sense of not knowing how the spatial miracle was created (or by whom in the case of a baroque church). NMA was painted as an allegory of Australian history figured as an unfinished conversation or contest between invisible and knotted threads of space; such storytelling seems remarkably appropriate for a national museum of a democratic country. Layered upon the miracle of creation and the allegorical were tectonic quotes or samples from architecture, the history of architecture, the history of the history of architecture, politics, the history of politics, the architecture of politics, the politics of architecture and so on, in another never-ending sequence of – in this case – referentiality.

These quotes, be they from architecture, architectural history or politics, were and are all powerfully local, though often of international origin with intense localized inflection or dialect. At the time Howard Raggatt talked about hoping “to make a place vividly local, rooted in Walter Burley Griffin’s garden city, rooted in the local country … ” In fact NMA was so referential that Macarthur thought that for the public a printed guide was required to fully understand the NMA and appreciate the quotes from Le Corbusier, Saarinen, Libeskind, Griffin, Stirling, Utzon and Peter Hall, among others. But for most, and without the guide, the undoubted experience is of Raggatt’s vivacity.

The architecture seeks to provoke symbolic interpretation.

Image: John Gollings

At Perth Arena the quest for never-ending movement continues, this time in the form of a circular or, more accurately, elliptical sequence of constantly changing elevations and interior public spaces, but the story or allegory of the project is harder to locate. Sport stadium as the new cultural arena? Again reference and inspiration abound, but Perth Arena is devoid of quotes from modern architects and instead references puzzles, Renaissance ideal cities such as Filarete’s Sforzinda and the twelve-sided 1829 Fremantle Round House, the oldest extant building in Western Australia. Not that puzzles are new territory. ARM said of NMA: “Instead of any singular entity we envisaged a series of intensely adjacent structures, like puzzle pieces.” And in 1994 the jigsaw puzzle was used in the ARM competition entry for the Melbourne Museum (Transition, no 46, 1994), albeit rhetorically rather than spatially.

Circulation spaces form a string-like sequence wrapping around the central arena.

Image: John Gollings

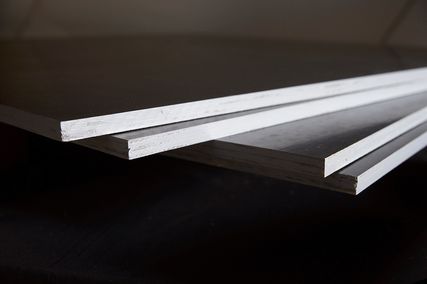

In the Perth Arena the puzzle is no longer simply metaphor or rhetoric but rather the thing itself, and it is certainly not the jigsaw puzzle of one’s youth. Here the puzzle is Christopher Monckton’s very complex 1999 twelve-sided Eternity Puzzle of 209 irregularly shaped pieces of equal area, thought to be so difficult to solve that a one-million-pound prize was offered for its solution. ARM used the equilateral and half triangles of the puzzle geometry to agglomerate twelve giant puzzle pieces in the form of abstract maps, trucks and swans to be stood up around the twelve sides of the arena’s inner bowl.

The venue seats 15,500 for concerts and slightly fewer for sporting events.

Image: Duncan Barnes

And the ideal city of the Perth Arena is not so ideal. It is not the perfection of the eight-sided star of Sforzinda containing public squares and civilization but a strongly distorted twelve-sided and three-dimensional (more or less) pantheon to sport and pop music. In both the ease of circulation of the populace is paramount. In both civilization is nurtured by collective engagement.

Inside the Perth Arena is a cosmic labyrinth of spatial delight. Klein blue is a signature colour.

Image: John Gollings

The public spaces in typical sporting and concert venues are rigorously utilitarian, but here they form a string-like sequence wrapping around the central performance space, much in the manner of a necklace of abstract uncut gems. The fact that one can circulate the entire arena bowl strengthens the experience of attending a collective event. Without this gesture one is separated from other attendees – one might as well stay home and watch the spectacle on TV.

Illuminated faces speak to each other in the mesmerizing interior.

Image: Robert Luxford

All stadia have the dilemma of having to defer to the primacy of the central space. The calm interior of the arena with roof open is very like the monochrome interior of the Round House. Very deliberately the quality of the public spaces exceeds that of the central arena. Such an inversion shifts the focus of attention away from the performer towards the public; the public becomes just as important as the performer.

Nothing in the arena is uniform or repeated. There is no overt controlling grid or parti. No regularity. But from all the seeming disorder there is the luxury of the principal public circulation and hospitality spaces. This remarkable quality of the arena is derived entirely from the brilliance of the architect’s imagination and not from material excess or highly controlled order. Yes, it is very well detailed and built, but the story of the Perth Arena is one of exaltation of public life, both the public life of the basketball/music fan and the public life of a city.

Perth Arena, like NMA, is full of creation stories, here played out by recasting the Round House as a swollen multi-faced metal-and-glass Trojan Horse in a retelling of the origin myth of Western Australian urbanism. Local form, local materials rendered in wide-screen vivid colour for the MTV century. Again, not surprisingly for an ARM project, there are further layers to the architecture and the stories. For, in another version of the origin myth of Western Australian urbanism, the only comprehensive history of architecture in Western Australia, Western Towns and Buildings (edited by Margaret Pitt Morison and John Graham White, 1979), has on its cover a juxtaposition of the Round House with the geometrically pure 1976 Allendale Square tower, the most celebrated example of the two-material architecture of metal panel and flush glass developed locally by Cameron Chisholm Nicol, ARM’s joint venture partners on the arena, and used exhaustively in buildings like Wesfarmers House and Austmark Centre. In this way one can view the Perth Arena as the next generation of architectural progeny of a founding figure, a metallic bloodline and a booming economy. Whether by natural selection or induced mutation or genetic modification, it matters little. “Optimus Prime,” one of the Arena’s most widely used nicknames, is the result.

Importantly, the scale of the Perth Arena is very unlike that of the delicate NMA; it is more akin to the coarse giantism so commonly found in the best Perth public buildings. From afar the arena appears as a craggy silhouette of crushed surfaces (hence the builder’s prescient moniker “the crushed beer can”); up closer it is a prismatic entertainment machine (hence “Optimus Prime”); from inside it’s a cosmic labyrinth of spatial delight highlighted in International Klein Blue and the celestial blue skies of Perth (hence “the spaceship”).

Twenty years ago the ARM scheme submitted in the Melbourne Museum competition used the concept of fractional dimensionality whereby a building can be perceived very differently depending on the location of the viewer or user: dimension 2.5 is thus used to define a building or object that may seem two-dimensional from afar yet three-dimensional from a closer vantage point. For example, from an aeroplane a coastline appears as a line on the surface of the world, yet a walk on the beach shows the coastline is much more than a line. The Perth Arena takes dimensionality in architecture to another level altogether. In the description of the project the architects talk of being “inspired by” puzzles and old buildings, the experience of a public building and looking out on a city. They seek to “provoke symbolic interpretation” and to create “extreme variability” from every angle. Other architects favour personal revelation over mediated inspiration; they service rather than provoke, denounce symbolism and interpretation in favour of authenticity and intentionality, design rather than create, avoid extremes and crave the uniform. The Perth Arena is a mesmerizing homily for the path being travelled by ARM Architecture and its partners.

Credits

- Project

- Perth Arena

- Architect

- ARM Architecture

Australia

- Project Team

- Stephen Ashton, Dominic Snellgrove, Howard Raggatt, Stephen Davies, Peter Keleman, Andrew Lilleyman, Jeremy Stewart, Jonothan Cowle, Andrea Wilson, Jacqueline Cunningham, Steve Christie, Luke Davey, Beata Szulc, Jonathan Davis, Greg Stretch, Doug Dickson, Michael Edmonds, Ian Surtees, Deborah Binet

- Architect

- Cameron Chisholm Nicol

Perth, WA, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

AECOM

Arena consultants RTKL Associates

Builder BGC

Building services WSP Group

Building surveyor John Massey Group

Civil consultant Wood & Grieve Engineers Perth

Landscaping Urbis

Project manager Appian Group

Quantity surveyor Ralph Beattie Bosworth Pty Ltd

Structural Aurecon Perth

Wayfinding Vivid

- Site Details

-

Location

Perth,

WA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial, Interiors, Public / cultural

Type Sport

Source

Project

Published online: 31 Oct 2013

Words:

Simon Anderson

Images:

Duncan Barnes,

Greg Hocking,

John Gollings,

Peter Bennetts,

Robert Luxford

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2013