Architect Sean Godsell.

Image: Earl Carter

Of all the architects I’ve met, Sean Godsell is the most Howard Roark-esque. Tall, muscular, with a chiselled face, he could almost be the physical description of Ayn Rand’s architect antihero in The Fountainhead. But for me the similarity lies mostly in Sean’s propensity to bluntly speak his mind and his refusal to compromise.

Like Rand’s now unfashionable protagonist, Sean has run foul of his educators, who twice tried to expel him from architecture school, and of others within his profession. He has never been afraid of a fight. Unlike Roark, however, he seems unlikely to be destined for obscurity. He has been published and awarded around the globe. A palpable aesthetic determination has made his buildings among the most distinctive in architecture.

His father was an architect and from an early age Sean wanted to be one too. AFL football, at which he excelled, threatened to derail him until injury knocked him out of the game at twenty-one, allowing him to refocus on his studies.

Early in his career, Sean coolly and dispassionately made decisions about his craft that have set his path ever since. He wanted to avoid polite architectural practice. He didn’t want to take a road that would lead to sentimentality about modernism, or play Melbourne’s postmodern game. Simply, he wanted to be different.

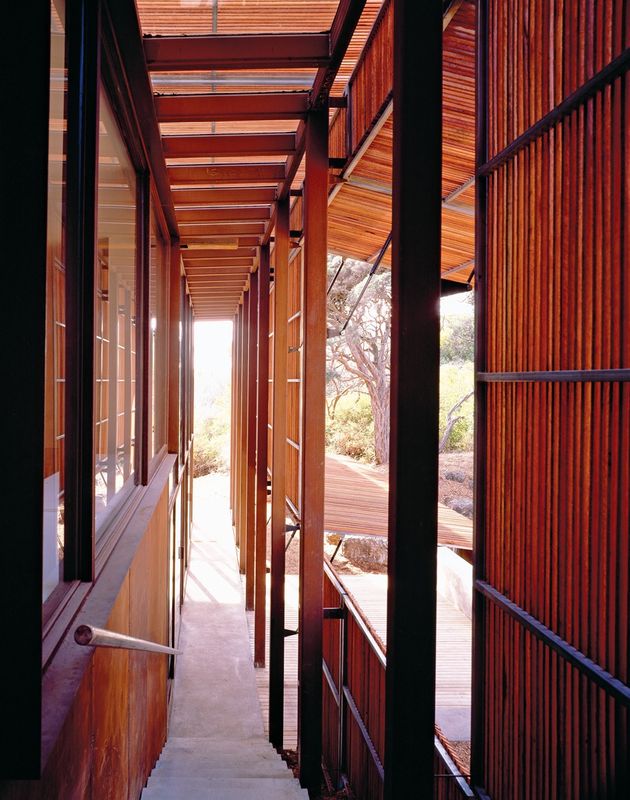

Primarily he looked for an expression that placed him in the region, in Australia and in Asia, devices common to both East and West. He examined the aisle in Eastern architecture, particularly in Japanese and Chinese disciplines, and its use as a fluid, undefined circulation space. He looked at the verandah of Australian rural homesteads and Queenslanders, which could be whatever you wanted them to be – a covered sitting area, a sleep-out, an enclosed perimeter space, a circulation route.

He further abstracted the verandah into a protective skin and for the most part removed sectional gymnastics from his thinking. He abandoned the corridor, which immediately de-Westernized his plans, and developed instead his own versions of the Eastern divided plan, where space is articulated by sliding walls and doors.

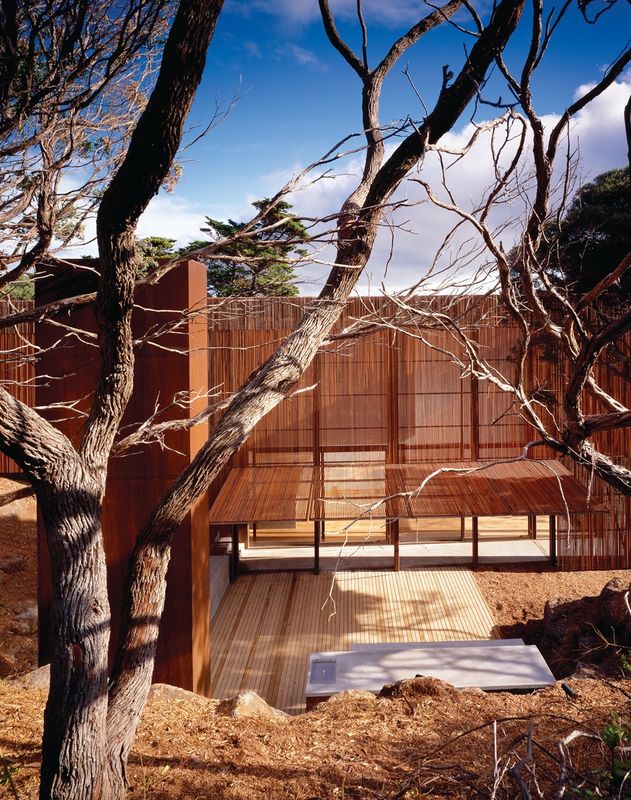

Carter/Tucker House (1998–2000): fluid, ambiguous spaces and undefined circulation characterize the work of Sean Godsell.

Image: Earl Carter

In the Carter/Tucker House, a coastal retreat for a photographer and his partner, the lower two floors can be divided into discrete spaces by sliding walls. Tilt-up panels in the timber-battened facade open like awnings to create a verandah-like room in the interior. With the sliding wall closed, a private space is retained while the “verandah” becomes the circulation. This idea of fluid, ambiguous space has never left his work.

The owners of both the St Andrews Beach House and the Glenburn House are office-bound in climate-controlled workplaces during the week. Not content, nor polite enough to provide them with enclosed circulation, Sean pushes them to a verandah/aisle, making them go outside in order to get back inside. Moving from the comfort of the bedrooms to the comfort of the living rooms exposes them to the chills of winter and the heat of summer. It’s a deliberate ploy to force a reconnection with nature.

Each of Sean’s buildings has a skin. It’s the most immediate signifier of his work. It is partly an extension of his thinking about the verandah – abstracted yet still providing shade to a building – but it also subverts the conventions of a facade. “By shrouding a building you completely redefine what an elevation might be. A door, a window in a wall ceases to be there.”

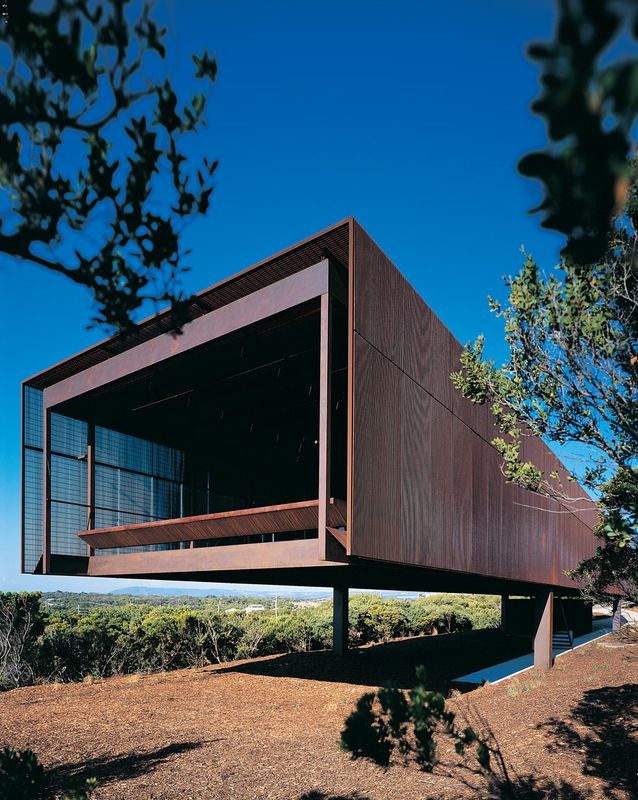

Glenburn House (2004–2007): from a distance, it looks like a monolithic, rusting steel sculpture embedded in the landscape.

Image: Earl Carter

The tectonic layers of his skins create beauty. Particularly in projects like the St Andrews Beach House, the Tanderra House and the Glenburn House, what can look like a monolithic steel sculpture from afar, a great rusting hulk embedded in the landscape, actually reveals unexpected permeability, transparency and shadow.

The St Andrews Beach House and the Peninsula House developed the skin further by making the roof, like the walls, a source of filtered light. Particularly in the latter case, the house is looked down upon from various vantage points. Also, Sean says, “By giving the roof parity with the walls, it removes an identifiable element from the building and you can create confusion about what is a wall and what is a roof.” Especially in the Peninsula House, internal structural layers are used to create differing levels of privacy. At Glenburn the skin is embedded with technology and power-gathering solar panels, as the discs on his futureproofed RMIT building will be one day.

Sean’s sections are mostly very simple. Apart from the Carter/Tucker House and the Peninsula House, where he says “the section is rampant,” the life in his buildings exists between two straight lines – a ceiling and a floor. Again, this was a specific decision at an earlier point in his career. Floor level drops and ceiling height lifts were discarded as a Western modernist device to be avoided. “The section is completely removed from the architectural argument and space is modified and manipulated in different ways, and that again brings the building back into an Eastern realm.”

The buildings can look tough, raw and crude, outside and inside, but the apparent brutality of the materials is deceptive. Inside they are surprisingly sensual. “They are tactile, usually with a warm, earthy palette. They are not severe in the same way that an all-white modern interior can be.”

Edward Street House (2008–2012): bands of inhabitation run across the site, from public to private space, and are mediated by galleries.

Image: Earl Carter

Most of the houses in this essay are objects in the landscape, which is why the recent Edward Street House is so interesting – his first suburban project since his own Kew House fifteen years earlier. It is essentially an alteration and addition, an extension to a heritage dwelling added on to the back like so many projects in Australia, but unlike all of them.

The client came to the office with an idea of an urban farm. That implied galvanized steel cladding, and though the context is suburban and constrained by a site rather than the broad brushstroke of a landscape setting, the house has developed along similar lines to the earlier works. This is possibly Sean’s most refined and sophisticated interior, beautifully detailed in recycled blackbutt but still within a box with a rugged, adjustable facade.

In this more urban context, Sean plays with layers of privacy. Instead of the classical approach – creating more privacy along the long axis of the site – bands of privacy run across the block of the plan, from side boundary to side boundary, separated by sliding openings and dividing walls.

Entry, at the side, is to the most public space – a gallery that glimpses and opens into the living spaces. Then there is a band with a library and study at either end and a laundry, bathroom and toilet in between. Finally, another gallery provides access to the most private zones, the bedroom and private bathroom. Both public and private spaces open into shared courtyards through the usual device of tilt-up screens.

Sean has also become known for his projects for the displaced and homeless. He puts it down to his Jesuit education. “You have to be a man for other people.” These endeavours provide a counterpoint to his bespoke work.

Future Shack (1985–2001): relief housing in the form of a repurposed shipping container.

Image: Earl Carter

His Future Shack, relief housing in the form of a repurposed shipping container, gained some attention when it was exhibited at New York’s prestigious Cooper-Hewitt museum in 2004. Nevertheless, this and other inventions for transformable bus shelters and park benches equipped to provide some comfort for people on the streets have gained little traction. No doubt he will continue to do what he does – uncompromised, determined, with his own rules for guidance.

The mental toughness from his days as an elite football player has surely infused his professional character. He has had the stamina to work for decades essentially solo or with one or two others. Hayley Franklin is his longest-standing collaborator. Sean still sketches, with pencil and paper, hundreds of drawings and ideas. One senses that he has a relentless approach to his craft, refining and refining, getting better and better with each new work.

Source

People

Published online: 24 Oct 2013

Words:

David Clark

Images:

Earl Carter

Issue

Houses, August 2013