Portrait of Ken Maher by Brett Boardman.

The architecture of engagement. Celebrating Ken Maher, recipient of the Institute’s highest honour, with tributes by Elizabeth Farrelly, Helen Lochhead, Philip Thalis and Matthew Pullinger.

JURY CITATION

The Gold Medal is the Australian Institute of Architects’ highest accolade. It recognizes distinguished service by Australian architects who have designed or executed buildings of high merit, produced work of great distinction resulting in the advancement of architecture, or endowed the profession of architecture in a distinguished manner.

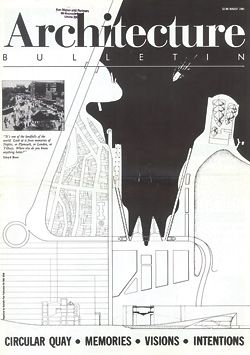

Ken Maher has excelled in all areas. He graduated from the University of New South Wales with First Class Honours and the RAIA prize for design, and with others won equal second prize in the international competition for the Pompidou Centre in Paris. During the ensuing thirty-eight years Ken Maher has played a leading role in our profession, most specifically in his role with Hassell since 1993. His projects have won prestigious awards including RAIA Merit Awards, the 1988 Canberra Medallion, the 1995 Lachlan Macquarie National Architecture Award, the Sir Zelman Cowen Award in 1998, Sulman Medals in 1998 and 2002, and national AILA awards. He has won a number of national and international competitions, is a respected design jury member, a teacher of design and currently Visiting Professor in Architecture at the University of New South Wales, and writes regularly about architecture. He has actively contributed to his profession, serving on numerous Institute committees and juries, as editor of the Architecture Bulletin in the 1980s, leading the NSW Chapter in 1993–1994 and serving on National Council’s Executive in 2000–2002.

Ken Maher’s tertiary education spanned architecture, landscape architecture and environmental studies, and his career reflects a lifelong interest in the bigger context of urban design, landscape setting and better buildings. As a director and now chairman of Hassell, he has broadened the firm’s horizons and through responsible delegation and mentoring has provided relevant opportunities and enhanced skills to those working with the practice. With Hassell he championed design and collaboration, supported emerging talent and the practice’s growth into Asia.

In design, Ken Maher’s attention is firmly focused, from public policy in the broadest sense to the specifics of an individual building. His urban design projects result in memorable, popular spaces such as the restored Luna Park in North Sydney and the Chifley Square and Cafe in Sydney’s CBD. Many recall the journey through the Olympic Park Railway Station not only for being part of the crowd but for its spaces and ambience. His National Institute of Dramatic Art buildings in Sydney transformed a typical education complex into an inspiring venue for live theatre. Overseas he has provided the concepts for an innovative new sustainable city centre in Ningbo, China and leads the design team for the new underground railway station in Singapore. Currently he is designing a vast new workplace for the ANZ Bank at Melbourne’s Docklands.

Many architects agitate on public issues, but few can drive change as positively and constructively as Ken Maher. As chair of the NSW Premier’s Urban Design Advisory Committee, the complex negotiations he resolved between government and the various stakeholders were impressive. A major outcome was SEPP 65, which requires the involvement of an architect for larger, denser residential projects and ensures measurable design and environmental outcomes.

In recent years Ken Maher has served on the City of Sydney’s Public Art Advisory Panel and chaired its Design Advisory Panel, where his influence has allowed wisdom and commonsense to dominate the proceedings. He was a founding director of the Green Building Council and is a recent appointment to the new Commonwealth Innovation Council for the Built Environment.

Ken Maher is a masterful collaborator and negotiator, with a calm and considered manner. His ability to identify the important issues and chart a clear course through conflicts has served the public interest on numerous occasions. His projects and our profession clearly benefit from not only Ken’s creativity but also his intelligence and civilized demeanour.

The Australian Institute of Architects recognizes and honours Ken Maher as the 2009 recipient of the Gold Medal.

Jury: Howard Tanner (chair), Greg Howlett, Richard Johnson, Alec Tzannes, Elizabeth Watson-Brown.

Only Connect

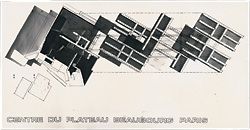

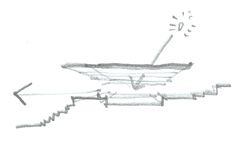

Competition entry to the 1971 Paris Pompidou Centre Competition, by Ken Maher, Colin Stewart, Craig Burton and Richard Apperly. The scheme was awarded second place.

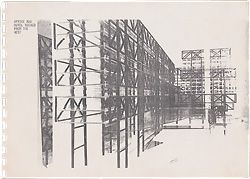

Final-year student project by Ken Maher, Colin Stewart, Mike Berry and Craig Burton, “a non-tower, ‘slightly Archigram’ mixed-use redevelopment of Sydney’s old Trocadero/Regent Theatre site”.

Elizabeth Farrelly looks to Maher’s life and his ideological arc to explain the depth and breadth of his engagement.

Ken Maher is that rare thing, a top-flight architect who writes publicly, reads widely and, despite an obvious depth of commitment, takes neither the job nor his own role in it too seriously. This alone is refreshing in a big-ego profession, but there’s more. For it’s not just a personality trait, some cloak of pseudo-modesty, but part of a coherent philosophy of the kind that few architects can sustain, much less articulate.

The day we meet, Maher has been reading Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature, design’s epic poem of connectivity. Re-reading, actually, four decades on. And as we talk it becomes clear that, while most are still working up to a first run-through, Maher has long since absorbed and metabolized its thesis as a guiding principle. Connectivity is my word, drawn from E. M. Forster’s “only connect”. Maher calls it engagement – an architecture of engagement.

It’s a theme that unites every aspect of Maher’s architectural life, from his insistence that “architecture is a team event” and that the best design comes from interaction (and yes, all architects do say that, but Maher means it) to his lifelong view that “architects need to engage at a political and public level” and his early adoption, well before either urbanism or eco-design were fashionable, of landscape design as a model for architectural practice and thought.

Raised Presbyterian, raised country, Maher describes himself even now as “a bit of a hopeless idealist”. In a place called Macksville, halfway between Coffs and Kempsey, his dad was a cop – “a very gentle soul, very engaged in community life” – and his mother taught preschool. And whether or not these rural beginnings really explain the matt-finish straightforwardness that has become Maher’s defining mark, such an hypothesis is both tempting and plausible.

Coming to architecture in the sixties, Maher chose “New South”, known as the most radical of Sydney’s university schools, where part-time practitioner-tutors included leading moderns Harry Seidler, Neville Gruzman, Keith Cottier, Harry Howard, Bruce Rickard, Richard Apperly and Peter Kollar. Plus of course the recusant Bill Lucas, who was to become Maher’s tutor, mentor and, briefly, employer.

As a freshman, after a 1966 student convention in Perth featuring Buckminster Fuller, Aldo van Eyck, Jacob Bakema and John Voelker, Maher quickly came under Lucas’s iconoclastic spell – even teaching design classes for him while still in second year.

Lucas excelled in dissent. Having studied architecture late as a returning WWII serviceman, he was optimistic, idealistic and appealingly counter-cultural but also profoundly sceptical, suspicious of all things corporate and, recalls Maher, “always in trouble with the university bureaucracy”. Unlike many of the beat generation, however, he was also determined to instil rationality into the design process.

Maher’s student years, as the Zeitgeist demanded, comprised architecture and politics in roughly equal measure, with much energy spent organizing events, building geodesics, becoming student president and participating passionately in the Utzon dismissal protests. So passionately, in fact, and so disgusted was Maher at the RAIA’s appeasement of the Askin-Hughes faction that for the next decade he boycotted the Institute by refusing to join. (This radicalism passed, as radicalism tends to, and another decade later he would take his turn as Institute president and now, from a desk with a full view of the Opera House, peppers his conversation with moderators – “I’m not a zealot …”, “I’m not a radical thinker …” – and with defences of being in the tent, not out.) Back in final year, however, Maher found himself allocated to the great cartoonist- architect George Molnar as studio master. Molnar, widely loved for his Sydney Morning Herald cartoons, took a strict, authoritarian view of both design (witness his International Style entry in the Opera House competition) and teaching. The regime that others – including 2008 Gold Medallist Richard Johnson – found stimulating proved, for Maher, intolerable. After a week he left, resolving to complete his final year part-time instead, under the wordly and enigmatic Richard Apperly. At the same time Maher worked part-time for Lucas and continued to draw inspiration from him – Lucas’s fierceness rivalled Molnar’s but his romantic-rationalist belief system was diametrically opposite.

The final-year project that brought Maher his First Class Honours was a non-tower, “slightly Archigram” mixed-use redevelopment of Sydney’s old Trocadero/Regent Theatre site (now occupied by Norman Foster’s Lumiere) on George. Undertaken as a group project with Colin Stewart, Mike Berry and Craig Burton, the scheme was housed largely within a series of horizontal, two-storey box-section trusses of which Harry Seidler, as external critic, would (recalls Maher) remark, “This is visual seduction. That member is redundant – but I would have put it there as well, because it works.”

This scheme became the prototype for the same team’s runner-up entry in the Paris Pompidou Centre Competition of 1971 (they entered under Richard Apperly’s moniker because Apperly, unlike the rest of them, was a registered architect). The idea, says Maher, broadly paralleled Rogers and Piano’s winning scheme – drawing on similar ideas of form, exoskeleton and flexibility, of “exposed structure and gismos”, and of nesting a space-age building into ancient city fabric. Similar ideas, just “a lot less developed, a lot less sophisticated and a lot less elegant,” he concedes with a grin. For Maher, looking back, it seems perhaps that their Pompidou concept was the Lucas glasshouse writ large. Either way, these two collaborative successes, in close succession, set him on the path to “engagement-type practice, rather than sitting alone in a room”.

By 1974, within four years of graduating, Maher had completed his first postgraduate degree, a master’s in computer-aided design. It was a prescient move but, for someone so 6B-friendly and so focused on architecture’s experiential nature, an obvious wrong turning, something he now dismisses as “probably a waste of time”.

By contrast, Maher’s abiding entanglement with landscape, as both passion and discipline, began almost by accident. To enrich a new bushwalking hobby, he undertook an adult education course at Ryde School of Horticulture. This course, taught by Don Blaxell, sparked Maher’s ongoing interest in ecology. More than that, it played on Lucas’s intuitive rationalism to make Maher think more broadly – well before urban design came into vogue – about context. He became fascinated by “how projects fit into things: in knowing more about the whole in order to understand the part.”

So it’s hardly surprising that Maher’s next postgraduate enterprises were diplomas in landscape design (1976) and in environmental studies (1986), the latter under the radical leftist thinker Leonie Sandercock. Sandercock, now the Vancouver-based expert in “mongrel cities”, was another lasting influence on Maher, making him see city form as reified politics, rather than just urban-design pattern making.

By 1974 Maher was a director of Nielsen Warren and Mark Windass Architects. By 1985 he’d set up his own practice, Ken Maher and Partners, along with a small landscape practice, Forsite (that later merged with EDAW), both operating out of shared space in an old warehouse in Ultimo and later another one on Kent Street.

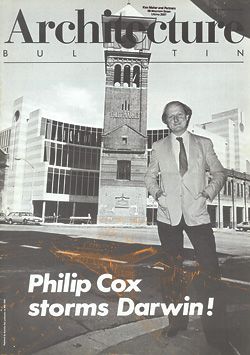

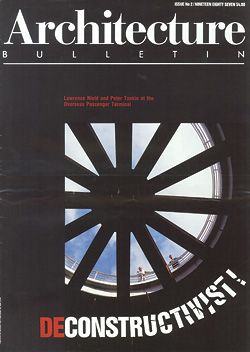

But running two practices and being father to two kids was barely enough. Maher was also teaching studio at Sydney (1980–90), editing the Architecture Bulletin (1983–88, with design by James Grose, threatened lawsuits by Philip Cox) and proselytizing the cause of urban design in Sydney.

It was under the aegis of then-RAIA President Chris Johnson’s 1983 Cities in Conflict convention that Maher invited fifteen architects to produce design ideas for the down-at-heel Circular Quay, publishing the results in a memorable volume called Quay Visions. It was classic Maher, to highlight an embarrassing problem in such a positive and, yes, engaging way that the city fathers began for the first time to see the Quay as design-capable, and design-needy, resulting in a special-purpose Ministerial Committee and the major Bicentennial upgrade of 1988.

It was around this time that I first met Ken Maher, when he was one of the style gang, the intelligent, articulate, forty-something practitioners – Alec Tzannes, Wendy Lewin, Neil Durbach, Peter Tonkin, Richard Francis-Jones, James Grose, Philip Thalis and (when he was around) Haig Beck – who not only practised architecture but taught, debated, competed and exhibited with equal flair and vivacity. These were the people who gave the Sydney architecture scene its bubbling energy, proving that there was creative life under the then very weighty canopy of Cox, Andrews and Nield.

It was they, too, who established the short-lived, oft-ridiculed Tusculum Club. Intended to rival Melbourne’s Half-Time Club and sometimes seen as mere penguin-suited pretention, it was a sincere attempt to encourage debate. Even now Maher believes architects “need to know more and speak more”.

“I have rather an old-fashioned view,” he says, “that professions are important, that with the privileges come obligations, that the job is not just one of service, but of advice.” And it was during his term of service as president, in 1993, that the Big Leap came, changing everything about the way Ken Maher was seen in the small fishpond of Sydney architecture. Suddenly the small, leftish Ken Maher and Partners merged with the large, old, stuffy South Australian commercial firm, Hassell.

The ease with which Maher accomplished this move, from the pristine clarities of small practice to the inevitable compromises of a large corporate one, surprised many. But Maher himself remains sanguine. For him the move simply attests his belief that architecture is bigger than the individual. “I was very interested in being involved in larger projects. I liked the profile of their portfolio, involving landscape and urban design. And, well, they asked me.”

He admits to having made some changes in his fifteen years at Hassell (the first two as director of Hassell Maher; the last six as Chairman), both to the strongly graphic red-and-charcoal office interior and to the practice itself, which he recast on an open-plan, flat-structure, studio-based model. But he has no designs on glory. “In Hassell,” he notes, “we deliberately chose a mode of practice that’s not about me or any of the leaders. We would never name the practice around the current individuals – it is a collaborative.”

Maher is clearly sincere in this, as when he says he is surprised and embarrassed, as well as delighted, to win Institute Gold. “You think you don’t believe in these things,” he laughs, at himself mostly, “but in the end, you do. It’s an honour – it’s just I haven’t really put myself in that league. I don’t see myself as a name architect.”

And yet he has transformed the firm’s image, won dozens of awards including two Sulmans and a Zelman Cowen, and is in such demand that he still travels constantly and globally to help “build a design culture” across Hassell’s 900 humans – including thirty partners – in twelve offices and five countries.

“I don’t think it’s about power,” he muses, although the accompanying laugh recognizes that that could be a factor. “I just wouldn’t be satisfied sitting in a room doing small houses in the bush. I think it’s about richness and complexity, and the challenge of working in and with public places.”

The Sulmans were for the very lovely Olympic Park Station (1998) and NIDA’s Parade building (2002). Both are hugely well deserved, the station being one of Sydney’s best spatial experiences and NIDA one of the few theatres to combine a real sense of occasion with art-school-black authenticity. There are other awards too, including the Luna Park restoration (1995), Chifley Square (1998), North Sydney Olympic Pool (2001), Fox Studios car park (2001) and Victoria Park Public Domain (2003).

Some – in particular the pool and the station – are especially photogenic. But for Maher, that is almost beside the point. “I am not the slightest bit interested in the architect as stylist or prophet, because I don’t believe it will last. The crossover between architecture, set design and fashion can be amusing and momentarily stimulating, but in the end it’s not important … Human experience is as much about engagement and relationships as anything else. Architecture can help make that circumstance, although sometimes, still, you feel overwhelmed by how difficult it is.”

So difficult he can’t stop. Even now, at sixty-one and chairing one of Australia’s biggest practices, he sits on half a dozen external committees and plans to resume teaching, one day a week. “It’s an experiment. If I commit myself I’ll have to be there.” He wants to do research, too, into cities: “We clearly can’t go on being profligate the way we have been. We need to be more knowledgeable about the impacts of what we do.”

Still, design is his love. He doesn’t have a favourite work, although when pushed will cite Roland Simounet’s Picasso Museum in Paris and the Parthenon as up there. Even among his own work? Well, maybe the Olympic Station. But really – and this is what keeps him going – “I’m interested in contributing to a betterment thing. Maybe it’s my Presbyterian upbringing, but I always want to do something better than the last.”

“My favourite project? Always my favourite is the next one. That’s just the way I am.”

Elizabeth Farrelly is a Sydney-based architectural writer.

NIDA PARADE THEATRE, SYDNEY, 1999–2002

Hassell in association with Peter Armstrong Architecture.

RAIA (NSW) Sir John Sulman Award, 2002.

Photographs Max Creasy.

See Architecture Australia September/October 2002, vol 91no 5.

OLYMPIC PARK STATION, SYDNEY, 1998

Hassell, for OCA.

AILA (NSW and ACT) Design Merit Award for Urban and Civic Design, 1999.

RAIA National Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Buildings; Access Citation, 1998.

RAIA (NSW) Sir John Sulman Award; Colorbond Steel Award, 1998.

Photographs Patrick Bingham-Hall (top) and Max Creasy (middle, bottom).

See Architecture Australia November/December 1998, vol 87 no 6, and The Architectural Review vol. 204, no. 1219, Sept 1998.

NORTH SYDNEY OLYMPIC POOL, 2001

Hassell, for North Sydney Council. 1998 national competition winner.

RAIA (NSW) Award for Public Buildings, 2001.

Photograph Patrick Bingham-Hall.

See Architecture Australia May/June 2001, vol 90no 3.

VICTORIA PARK AT ZETLAND, SYDNEY, 2000–2003

Hassell in collaboration with the NSW Government Architect’s Office, for Landcom.

Image: water fountain, artist Jennifer Turpin and Michaelie Crawford, edges Joynton Park.

Australian Award for Urban Design, Public Domain, 2004.

AILA National Merit Award for Design; Commendation for Environment, 2004.

RAIA (NSW) Lloyd Rees Award for Civic Design, 2003.

Photograph Patrick Bingham-Hall.

See Architecture Australia January/February 2004, vol 93 no 1 and Landscape Australia, September 2003.

crossing disciplines

Landscape, urban design, architecture. Helen Lochhead discusses Ken Maher’s cross-disciplinary work.

Ken Maher has worked comfortably and effortlessly across disciplines for most of his professional life. Following his architecture degree he was drawn to study landscape architecture and later environmental studies at Macquarie University. These early forays beyond architecture fostered his interest in the broader landscape and larger environmental systems, ecology, geography, how cities are formed and ultimately urban design.

These timely influences were critical in the development of his design approach, which has without exception been informed by the larger context. This focus has also informed the way he works, which is not only multidisciplinary in approach but strongly collaborative in practice. His notable projects are by and large team efforts comprising diverse creative and professional disciplines.

Being a collaborative designer and strategic thinker has enabled Ken to straddle a vast variety of work, from urban policy initiatives to masterplanning to urban infrastructure projects through to smaller projects and public spaces of detail and complexity.

Despite the breadth and diversity of this work, it is in the main high-profile public work, confirming his enduring concern for the critical role of design in contributing to public life and a sustainable future. The motivation to “make a difference” and design with the public interest is obvious across his portfolio of work.

Other early influences, like the architect Bill Lucas, encouraged Ken to strip things back to their essence in the modernist vein. Bill’s design teaching provided the early foundations for Ken’s rational approach, which combines invention and functionality, somewhat tempered by his own desire to create spaces that heighten experience and delight. These many influences are apparent in his public projects to varying degrees.

An interpretation of the geography of the larger context provided the genesis of many of his projects. At North Sydney Pool, the design competition brief demanded a new indoor pool. A logical extension adjacent to the existing pool was stipulated but Ken’s noncomplying approach sited the new pool above the existing grandstand. Inspired by the rock platforms perched over Sydney Harbour, this scheme challenged the brief and created a floating canopy above the ground plane, and won the competition. A simple, elegant structure, it hovers over the pool and grandstand. Even the walls of buildings appear to dematerialize to allow the harbour setting and climate to penetrate.

The modulated ground plane and floating canopy were also key generators of Sydney’s Olympic Park Station. This could have been a typical underground station that pops up anonymously within the built environment. It could have been just another development opportunity. Instead, arrival is celebrated in a space awash with daylight, dramatically expressed by a soaring canopy and a ground plane that extends the public realm into and through the building. The station is a truly egalitarian and major public space.

At the National Institute of Dramatic Art, a collaboration with Peter Armstrong Architecture, the new theatre complex transformed the cloistered educational institution into an engaging showcase for the Parade Theatre. The theatre is sheathed in coloured louvres. Public spaces wrap the theatre volume and address the street with another grand canopy, revealing the life and activity within the building. Again in this project, the facade seems to disappear at dusk and only the roof remains. This luminous, vibrant foyer space animates the night and heightens the ambiguity between the interior and the public domain.

A fascination with the ground plane and the canopy is also evident in Ken’s concepts for smaller public spaces in Sydney, the Haymarket project and Chifley Square. The Haymarket was developed with artist and architect Peter McGregor of McGregor Westlake. A series of small, chaotic streets through Chinatown were given a simple clarity and order with the insertion of a series of aerial structures that span the streets and celebrate the intersections. Virtually invisible by day, when illuminated at night this abstract interpretation of Asiatic street lighting not only delights but transforms the experience of these ordinary streets into extraordinary spaces after dark.

Working with the City of Sydney’s City Projects unit at Chifley Square, the designers sought to provide a formal order to this amorphous public space. This was done with a grid of Sydney’s characteristic Cabbage Tree Palms overlaid across the square, the road and the footpath opposite. The simple ground plane and uniform canopy of palms of the same height datum served to unify and order this previously nebulous space.

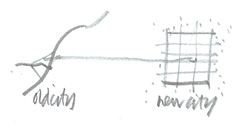

At a different scale, Ken’s masterplans interpret the geography and morphology of the larger context to inform his concepts. The winning competition scheme for a city extension to the City of Ningbo in China was inspired by the urban structure of the historic city. The old city has a formal grid of streets and canals. The proposal drew on these structuring principles to create a new sustainable city grid of streets and waterways, surrounded by an urban forest, which are intrinsically integrated into the environmental management of the new urban environment.

Similarly, holistic water management was a key driver for the new masterplan and public domain developed for Victoria Park at Zetland by Hassell and the NSW Government Architect’s Office. On this low-lying, flood-prone site, all stormwater was able to be managed through water-sensitive urban design principles. An innovative and cohesive public realm was developed, where the water management is expressed in a compelling and direct manner.

This combination of award-winning projects bridging the public ream, planning and sustainability have led to Ken Maher’s involvement in high-level city design and urban strategy issues. As chair of the NSW Premier’s Urban Design Advisory Committee, he was instrumental in the development and adoption of SEPP 65, which requires architects’ involvement in complex, high-density residential projects in NSW. He served on the inaugural Green Building Council and the City of Sydney’s Design Advisory Committee as Chair. Most recently he was appointed to the federal government’s Built Environment Industry Innovation Council.

In addition to his practice and advisory roles Ken has maintained an ongoing involvement in education and design. His public lectures and published articles are also testament to his public engagement and commitment to urban design. Notable topics include What Makes Cities Great (2006), Urbanisation in a Global World (2005) and Design in the Public Interest (1999).

While Ken Maher is recognized in Australia for his contribution to architecture, most notably through this Gold Medal, his contribution is demonstrably broader. Ken has worked across design disciplines including landscape, urban design and planning with ease and distinction and should be acknowledged for his substantial role and contribution to the broader disciplines of environmental and urban design.

Helen Lochhead is an architect and urban designer and Assistant Government Architect in the NSW Government.

NINGBO NEW URBAN CENTRE, CHINA, 2003

Hassell, competition for Ningbo Municipal Government 2003.

AILA National Merit Award for Planning, 2004.

AILA (Vic and Tas) Award for Excellence for Environment and Sustainable Practice; Commendation for Planning in Landscape Architecture, 2003.

Planning Institute Australia (Vic) Commendation for International Planning, 2003.

See Landscape Australia Sept 2003 vol. 25, no. 3.

CHIFLEY SQUARE, SYDNEY, 1996

Hassell, for City of Sydney with City Projects 2000.

AILA National Project Award for Design – Public Spaces, 1998.

Photograph Patrick Bingham-Hall.

See Architecture Australia March/April 1998, vol 87no 2.

HAYMARKET PRIORITY PROJECT, SYDNEY, 2000

Hassell, for City of Sydney. Artist: McGregor Westlake.

AILA National Project Award for Design – Landscape Art, 2000.

Photograph Patrick Bingham-Hall.

See Landscape Australia February/April 2002.

In the beginning

Philip Thalis recalls the intensity and enthusiasm of Maher’s early years.

Ken Maher is in many ways the exemplar of the contemporary architect, yet few in Australia can compare with the breadth of his achievements. His sustained contribution over four decades has delivered significant works of architecture and urban projects, collaborative cross-disciplinary work, the advancement of architectural culture and concerted engagement with decision makers and public opinion. Given Ken’s continuing vitality, the next decade and beyond promise to extend his successes.

Otto Wagner, in his 1895 book Modern Architecture, noted the tough challenges facing our profession: “The lifelong training of the architect, the responsibility connected with his creative work, the great difficulties opposing the realisation of his buildings … an unfortunately all too frequent envy, and the diversity of views among his colleagues invariably cover his path of life with thorns … the eternal grey of practice and eerie darkness of public indifference veil every free and cheerful prospect.”1 All of us battle constantly with such circumstance. To an exceptional extent, Ken has been able to transcend such inhibiting factors to forge a remarkable career, full of accomplishment.

Initially Ken’s intellectual curiosity and restless desire for knowledge were exercised in extended formal education. Not content with his First Class Honours degree in architecture from the University of New South Wales in 1970, he followed it with a Masters in Architecture in 1974, improbably for that era on the use of computers in architecture, followed by a Landscape Diploma in 1976, both from UNSW. An Environmental Studies Diploma, with a focus on urban issues, followed from Macquarie University in 1986. Success came early, with an astonishing second place in one of the major global competitions of the postwar era – the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1970 (with Craig Burton, Colin Stewart and Richard Apperly).

Nor did Ken neglect professional practice, quickly gaining registration and becoming a director of a succession of small practices, mostly in association with first Nielsen Warren and then Everard Kloots and Robin McInnes.

As a young architecture graduate in the mid-1980s, I found working with Ken illuminating. Ken embodied Wagner’s proposition that the architect is the “happy combination of idealism and realism”. The scope of his activities set a demanding standard and I saw first hand his commitment and energy, which challenged the lacklustre norms of design and practice and the stifling politics of the city.

In the profession, he was a NSW Chapter Councillor from 1983 to 1994, serving as President in 1993–94. He chaired various RAIA committees and co-wrote many submissions. He also acted as an awards juror in 1981 and in 1983, and was jury chair in 1992.

In the dissemination of ideas, Ken was an enthusiastic editor of the NSW Architecture Bulletin from 1983 to 1988, reinvigorating the publication to a level that many since have striven to maintain. Continually agitating for a more informed and ideas-driven agenda for Sydney, he also published Quay Visions and helped organize the City in Conflict international conference in 1983. In academia, he acted as a design teacher and occasional critic at UNSW and Sydney universities, teaching both architecture and landscape design.

In practice he was concurrently director of Quay Partnership, which became Ken Maher and Partners Architects, and Forsite Landscape Architects, which he established with Ian Oelrichs and John Van Pelt. Each practice had between twelve and eighteen professionals, plus shared administrative staff.

Add entering competition schemes with various collaborators, including a commendation in the Circular Quay Gateway Ideas Competition, second place in the National RAIA Tusculum Headquarters Competition and joint winner of the Woolloomooloo Ideas Competition. The Canberra Medallion for the Bruce Psychiatric Hostel in 1988 was the first of a stream of awards for architectural projects.

Ken’s practices had a youthful orientation, full of enthusiastic graduates working late. Collaborators from this period to have gone on to successful practice in Australia include Peter Stutchbury, Peter Ireland, Russell Olsson, Luigi Rosselli, Louise Nettleton, David Stevenson and Belinda Koopman in architecture, and Vladimir Sitta, Phoebe Pape, Tempe McGowan and Chris Thomas in landscape.

The intensity with which Ken worked was remarkable. Commonly he started work early and, after seeing the family for dinner, he came back to the office from 8pm till midnight on most days, was often in on the weekend, and made fortnightly early morning trips to project meetings in Canberra, as well as the RAIA activities in the evening. Throughout Ken maintained energy and focus. To sit down with him for even half an hour brought clarity and progress to any project, whether site strategy, design resolution, project briefing issue, presentation drawing or report. Rather than the ideological or grand, formal statement, Ken preferred to emphasize the best interests of the project, the clarity of the plan and the integrated environmental design, creating an enriched personal experience of architectural space. Always present was a well-founded understanding of the scale and operation of the city.

Yet despite such endeavour, Ken’s early practices struggled to find significant projects in booming Sydney of the 1980s. Only the NCDC in Canberra had the confidence to award the young practice worthy projects, including the Bruce Hostel and a primary school in Chisholm which was widely published. The major project in Sydney was the ill-fated Mort Bay project for the Housing Commission, which was mangled through an ill-conceived delivery process and political interference following a change of government. Several smaller projects such as the Narrabeen Sport and Recreation Hostel and several houses are the best buildings realized in this period. Surviving the difficult recession of the early 1990s, Ken took the opportunity to undertake larger scale projects and a new professional phase by joining with Hassell.

All who have worked with Ken in any capacity would recognize his many qualities of intellect, reflection, integrity, fairness and respect for colleagues. Not for him the prima donna persona, or the evils that Wagner so adeptly identified as the “hermaphrodites of art or the vampires of practice”. Ken Maher continues to be an inspiration: an exemplary architect, a model of enlightened public engagement and a commendable choice as the 2009 Gold Medallist.

Philip Thalis, principal of Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, worked with Ken Maher between 1985 and 1987.

1. Otto Wagner, Modern Architecture (1895), republished in 1988 by the Getty Center Publications Program, Santa Monica.

TUSCULUM COMPETITION, 2ND PRIZE, 1985

Ken Maher, Everard Kloots, Peter Ireland.

See Architecture Bulletin, May 1985.

CHISHOLM PUBLIC SCHOOL, 1986

Ken Maher and Partners, for NCDS and ACT Education Authority 1986.

Photograph John Gollings.

See Architecture Australia September 1987, vol. 76, no. 6.

STOMANN HOUSE, SYDNEY, 1985

Ken Maher and Partners.

See Architecture Australia May 1988.

BRUCE PSYCHIATRIC HOSTEL, CANBERRA, 1988

Ken Maher and Partners, for ACT NCDC Health Authority 1988.

Photograph John Gollings.

RAIA Canberra Medallion, 1988.

engagement, critique, speculation

Ken Maher has extended the architect’s sphere of influence and created an enduring legacy, writes Matthew Pullinger.

Doubtless, one measure of an architect’s worth is a body of work realized according to the system of controls that apply to a project and its site at a particular moment in time. We all know this familiar terrain of budget, client aspiration and planning regulation. As important as it is, though, the creation of good, even great, buildings is not the only way an architect might bring positive and enduring change to architecture and to the quality of the cities to which it contributes. To have an opportunity to operate beyond the architect’s usual sphere of influence, to be able to sway those who set the planning regime, those who adjudicate over it, to successfully shift a client’s values, to change the system of controls for the betterment of architecture – this is as remarkable as it is rare.

Ken Maher is a modest person, not motivated by any overt sense of self, so his career-long commitment to public engagement with issues relating to architecture, landscape architecture and urbanism is intriguing. Yet this interest in broader thinking and his unrelenting participation are among Ken’s finest qualities.

Ken’s concern and active involvement in public debate and policy intersect with a natural inclination toward the study of creativity, organizational culture, environmental awareness and collaboration. These themes have shaped his career and the practices he has led. Of course, he also possesses the attributes necessary to a great architect – resilience, patience, optimism, attention to fine detail and continual self-questioning and challenge.

The circumstance of large practice is more rewarding than might often register, although it necessitates a different view of collaboration and culture. Ken is a supporter of process – essential in larger organizations – but only to the extent that such processes support good design. Perhaps the most critical contribution Ken has made with Hassell has been to instil a culture of success and critical review, where the endeavour of many individuals in many locations is encouraged and supported. This is the greatest measure of Ken’s skill as a leader.

All leadership draws heavily upon the faculty for communication. In turn, good communication is based on engendering shared understanding. Ken is uncommonly adept at written, spoken and drawn communication. His drawings are fluid and expressive, matched by clarity in thought that is structured and articulate. Debate with Ken never flares into the defensive or negative. He is masterly in negotiation. In print, Ken replicates this same clarity with an economic precision that focuses on the quality of human experience ahead of the intangible.

When it comes to relationships with clients, Ken has said that his method is to “understate and over-deliver”. Given the alternative, it’s a compelling approach that regularly garners greater support and stronger loyalties than overplaying a client pitch is ever likely to.

Acting upon an invitation to work alongside Ken can be challenging, all-consuming and perhaps a little daunting, yet these emotions are not to be feared or experienced alone. Ken is a part of the project journey and part of the team, not an observer of it. This is particularly the case for complex projects undertaken at an urban scale, those that comprise multiple buildings and the public spaces that tie them together.

During the design phase of one such project – Hassell’s master plan for Darwin Cove, currently under construction – Ken was, as ever, a constant contributor to and leader of the project team. Additionally, throughout the scheme’s development and the subsequent negotiation with the Northern Territory Government, he advocated passionately for a truly democratic public space as the central identifying aspect of the scheme. It is this new civic parkland, clearly configured as a public realm, that will underpin the success of an important new mixed-use precinct that reconnects Darwin’s CBD with its harbour. It also creates a rich cultural and natural setting for the architecture that emerges from the master plan.

Ken’s capacity for work is quite profound and his involvement widespread. Yet he still seems to have time to share, motivated only by a desire to support others. At Hassell, Ken’s view is readily sought and heeded at all stages of projects, a mark of the respect earned and held here. His appointment in 1998 as a Visiting Professor to the Faculty of the Built Environment at the University of New South Wales reflects this longstanding commitment to teaching and sharing knowledge. So too does his involvement as a founding board member of the Green Building Council Australia and his more recent appointment as chair of the City of Sydney’s Design Advisory Panel.

In a similar vein, Ken’s achievement as chair of the NSW Government’s Urban Design Advisory Committee, particularly through that committee’s work in 2000 to lift the quality of design in high-density residential buildings, was unprecedented in Australia and remains unique to New South Wales. The recommendations endorsed and implemented by the Carr Government have brought about a measurable improvement to the quality of building design in New South Wales. Among a raft of more subtle adjustments to the state’s planning legislation, Ken oversaw the introduction of a widespread system for peer design review and – most significantly – the gazetting of a statewide planning policy mandating the involvement of an architect in the design of all high-density residential buildings in New South Wales.

A deep commitment to the profession of architecture, most importantly its practice and culture, has drawn Ken into an extended relationship with the Australian Institute of Architects. Highlights include stints as editor of the NSW Architecture Bulletin 1983–1988, NSW Chapter President 1993–1994 and National Councillor 2000–2002, alongside numerous other engagements and contributions over the last three decades. This involvement is based on the simple philosophy that our profession benefits from the dissemination of ideas through participation.

The Gold Medal is a well-deserved acknowledgment of Ken’s consistent involvement at the pinnacle of the profession, and my personal congratulation will certainly echo many others. To produce architecture of lasting significance is no simple feat. But to extend influence over architecture well beyond the act of realizing great buildings is an enduring legacy indeed.

Matthew Pullinger is a principal at Hassell and first met Ken Maher in 2000 when they implemented public policy lifting the quality of building design in NSW. Matthew joined Ken at Hassell in 2004 and has since worked closely with him on many projects, including the masterplan for Darwin Harbour.

WESTPAC PLACE, 2003

Hassell in collaboration with Geyer.

Photograph Max Creasy.

DARWIN EXHIBITION AND CONVENTION CENTRE, 2004–2008

Hassell and Crawford Architects (Architects in Association), for the NT Government, Sitzler Barclay Mowlem 2008.

Photographs Brett Boardman.

DARWIN COVE MASTER PLAN, 2004–2008

Hassell, for the NT Government and ABN Amro Consortium 2004.

See Architecture Australia March/April 2005, vol. 94, no. 2.

TIANJIN EXHIBITION CENTRE, CHINA, 2008

Hassell. Invited international competition, 2007.

Colleagues and Collaborators

Key design collaborators on various projects illustrated include:

Colleagues

Rob Backhouse

Matthew Blain

Julieanne Boustead

John Choi

Andrew Cortese

Robin Deutschmann

Debbie Eastment

Robin Edmond

Anna Fairbank

Nigel Greenhill

Tony Grist

Glenn Harper

Peter Ireland

Luke Johnson

Everard Kloots

Robin McInnes

Matthew Pullinger

Hugh Turner

Rodney Uren

Collaborators

Peter Armstrong

Peter McGregor

Jennifer Turpin

Michaelie Crawford

Simeon Nelson

Tim Williams

Stacey Jones