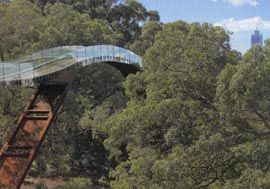

Looking along the elevated walkway through the tree canopy, with the Balga Lookout to the left.

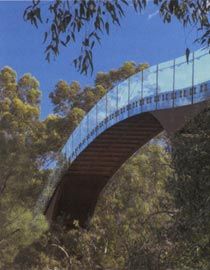

The slender ribbon-like bridge arcs across a small valley, evoking the journey of the dreamtime serpent, the Wagyl and providing uninterrupted views to the Swan River.

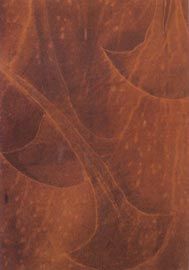

The finely worked surfaces of the walkway and bridge.

The finely worked surfaces of the walkway and bridge.

The bridge offers the visitor access to the upper tree canopy. Images: Martin Farquharson

Kings Park is Perth’s landmark public park. Located high on the Mount Eliza scarp, overlooking the city, it has an ongoing and highly significant role in the way the city has constructed an image of itself. The latest addition to this landscape, Donaldson + Warn’s Lotterywest Federation Walkway, provides new opportunities for engaging with the park and thinking about its layered histories.

The project is made up of five discernable elements and experiences. It begins with a pathway that moves through a series of didactic gardens to an elevated walkway that carries the visitor through a canopy of mature native Karri, Marri, Tingle and Jarrah trees.

A bridge then allows panoramic views of the Swan and Canning Rivers to the south, as well as offering an understanding of the significance of the site to the local Nyoongar people. A second walkway delivers the visitor back to the ground through what architect Geoff Warn calls a “cathedral of Marri trees” and links into existing pathways that reveal the rusted weather resistant (WR) steel pylons etched with the art of Kevin Draper. In many ways the project is sympathetic with the dominant picturesque mode of the park while also proposing new ways of thinking about non-European representational space.

The park has its origins in the early 1870s when a 175-hectare tract of land on the scarp overlooking the fledgling colonial settlement of Perth was designated as future public garden and parkland. In 1890 this was expanded to a total of 400 hectares and thus began a process of clearing, planting and manipulating; shaping, contouring and remodelling the native terrain into a European-style garden that remains in evidence today as Kings Park.

The elevation of the park makes it a popular vantage point from which to enjoy the framed view of the Perth CBD and a spectacular vista across the Swan River and beyond, across the flat sandy plains, to the Darling Scarp on the eastern horizon. This “viewing edge” – identified by Perth architect and academic Hannah Lewi as one of a series of narrative spaces throughout this extensive parkland – is significant as the location from which Perth’s development since settlement, has been recorded through countless paintings and photographs.1 It constructed a view that Lewi describes as “falling somewhere between the panorama, the topographic map and the picturesque, romantic scene” – an amalgam of many of the concerns of nineteenth-century landscape and garden design.

From 1900, the park also became a repository for monuments that helped to place the West Australian colony in the greater context of the British Empire. The imposing statue of Queen Victoria, the monument to the Boer War, and collections of munitions and artillery guns constituted and reinforced the collective memory of a culture at the fringe of an imperial domain. These two thematic strains – the picturesque and the European collective memorial – are both reinforced and challenged by Kings Park’s newest insertion.

The Lotterywest Federation Walkway begins with a pathway that integrates seamlessly into the established network of serpentine walkways. Of the five million park visitors a year, very few currently venture beyond the “viewing edge”, the war memorial and visitor’s centre. The pathway is designed to draw some of these visitors deeper into the park to enjoy its extensive Botanic Gardens. The path’s orchestrated meandering through gardens that represent the seven states of Federation, the Kimberley garden with its striking collection of boab trees and the Tuart Lawn, place it in firmly in the park’s established nineteenth-century picturesque tradition. The overt choreography of the pathway experience posits the visitor as viewer. The route is prescribed, marked with inset cast iron plates bearing the project’s logo, views are framed, scenes are set, landscapes manipulated. However, it also provides unexpected vistas – like the one through to fountains of the Pioneer Women’s Memorial, which is normally viewed from the opposite direction. It allows the viewer to make visual connections between a dismantled and repositioned Hosking’s 1897 rotunda and one further up the park in its original location. To these traditional notions of the picturesque D+W, with engineers Capital House Australasia, have added their own Modernist twist. An elegantly engineered parabolic timber roof from a demolished 1960s staff quarters is reinvented as a shelter and pavilion.

The elevated walkway departs from a small landing adjunct to the relocated Hosking’s Rotunda, where the sloping earth is folded up to create a “plaza” retained by 12 millimetre thick WR steel. The formal, tectonic language of the second stage of the project is thus established – bold, repetitive, monolithic forms, simply detailed. The structural support for walkway consists of elemental WR steel pylons. The same width steel is used for the walkway, decked with reeded jarrah, and the balustrade is simple welded WR flat bar with a galvanised steel handrail. The pathway cast iron panel is repeated as an inlay in the decking. Deceptively simple in plan and elevation, these repetitious objects become vastly more complex and visually arresting when viewed obliquely in the landscape. The broader expanses of WR steel pylons are as rich in colour and subtle variation as the paintings of Mark Rothko or Rover Thomas. The monolithic pylons and the vertical balustrades frame and define the landscape like the sculpture of Richard Serra. As well as transcending its simple forms to hover as an architectural mediation between engineering, sculpture and land art, the walkway draws attention to the significance of the location to Indigenous people. The footings are shallow and wide to avoid disturbing the ground dwelling ancestral spirits and the 16- metre spans allow for fewer pylons to be placed in the floor of the valley. The walkway provides a transcendental viewpoint that coincides with a botanical interest in the canopy of trees. A lookout halfway along its length mimics the form of an upturned grass tree.

The walkway changes direction awkwardly but then arcs elegantly across the small valley as the third element of the project. The ribbon-like thinness of the bridge is accentuated by the cast iron floor panels, embossed and cut out using the project’s double leaf logo which, when viewed from below, evoke the sensation of looking into the shifting light of the tree canopy. A glass balustrade allows uninterrupted views to the river and the controversially sited Swan Brewery below. After moving from the raw simplicity of the walkway, the applied graphics of the bridge appear superfluous. They seem unnecessary to the overwhelming gestural strength of the bridge that creates a powerful sense of the space occupied by the dreamtime serpent, the Wagyl. The Nyoongar Aboriginals say this ancient creature created this small valley on its way to the Swan River. The bridge gives a clear spatial sense of the scale of the transformation wrought by these ancestral creatures on Australian landscape.

The bridge then delivers the viewer to a second walkway, the Law Walk, beneath the Marri forest canopy. This walkway, closer to the ground, is detailed with an open mesh floor bringing the valley floor to the viewer’s attention. The design team worked in collaboration with Aboriginal arts consultant Richard Walley to include a performance space, Beedewong, for the Nyoongar people whose cultural traditions are maintained through dance and storytelling rather than painting. Past the amphitheatre, the walkway links into existing network of paths offering alternative routes through the garden. As the Law Walk moves underneath the bridge and walkway the analogy between Serra’s work and the walkway’s pylon becomes more obvious. Like Serra’s sculpture, the pylons simply appear as objects in a landscape. It is not until you are close to the great expanses of rusted metal that you realise that are actually finely worked with the addition of welded images – banksia leaves, seed pods, geological stratifications – ground back and scratched into the surface of the steel. Initially the applied outline of flora appears slightly naïve and superfluous, overwhelmed by the monolithic simplicity of the pylons. However, they are transformed by the weathering of the WR steel – the collection of water in the weld ridges create patches of golden ochre oxidisation, wind-driven rain streaks mimic the fall of seed pods, the areas exposed to sun become blackened as if burnt.

D+W’s walkway is a bold, contemporary insertion into a very traditional terrain.

The project successfully brings together the predominant nineteenth-century picturesque landscape with traces of the colonial eye, as well as suggesting new ways of comprehending the transformations wrought on the land from a much early mythic time.

This evocation of the journey of the Wagyl is one of the triumphs of the project. It proposes a contemporary architectural expression for Indigenous culture as well as providing a space for its narrative to be retold and renewed.

Credits

- Project

- Lotterywest Federation Walkway

- Architect

-

Donaldson + Warn

- Project Team

- Geoff Warn, Tom Griffiths, Jonathan Lake, Chris Mellor, Robyn Moore, Andrew Scafe, James Webb

- Consultants

-

Aboriginal arts consultant

Richard Walley

Access consultant Independent Living Centre of WA—Ann O’Brien

Artist Pylon Artwork—Kevin Draper; Aboriginal Artwork— Lyle Calyon, Jenny Calyon, Peter Calyon, Lance Chad, Shane Pickett, John Walley, Olman Walley, Richard Walley

Concrete works A. H. Civil—Alvin Harrison

Electrical engineer CCD Australia—Guy Tomlinson

Electrical services M & M De Luca—Mario De Luca, Andrew De Luca

Environmental artist David Jones. Graphic design Ray Leeves

Glazing Armourglass—Gerhard Trichard

Head contractor John Holland—Frank Dilizia , Peter Pugliese, David Grist

Landscape architect Plan E—David Smith

Landscaping Stillwater—Justin Byrne

Quantity surveyor Ralph Beattie Bosworth—Bruce Greenwood, Graeme Zorn

Signage and graphics Sean Elsegood Design

Steel fabrication upiter Steel—Russell Lang, Ron Browne, Alan Brown, Simon Van Hall

Steelwork shop drawings Appro Drafting—Andrew Poole

Steelwork-erection On-Site Engineering—Rob Nolan

Stressing and ground anchors Frilling and Grouting Services—Laurent Carles

Structural engineer Capital House Australasia—Brian Nelson, John Knuckey, Domenic Malatesta, Chris Samson

Survey control Fugro Surveying—Ash Craven, Mark Trichet

- Site Details

-

Location

Perth,

WA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority—Steve Hopper, Mark Webb, Roger Fryer, Grady Brand, Jacqui Kennedy; Friends of Kings Park—Tom Alford; Lotterywest—Andrew Walton

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2003

Words:

Philip Goldswain

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2003