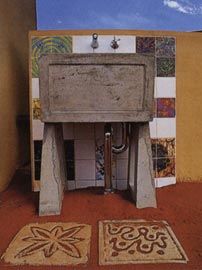

Detail showing a tub for artists to wash brushes or get water, and for people to fill up billys to make tea. The tiles are by the Warburton Women’s Centre.

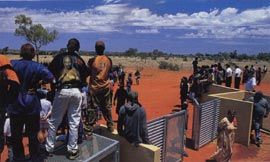

Opening day.

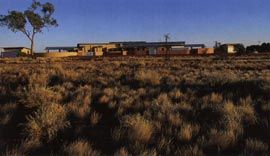

Looking north towards the centre.

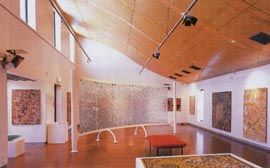

The interior of the gallery, which houses the Warburton Collection, the most substantial collection of Aboriginal art in the country under the direct ownership and control of Aboriginal people.

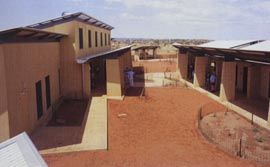

Scenes from the opening of the Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Centre, which Inside Out Architects designed to support and encourage existing living practices, etiquette and knowledge systems. The centre is described by Mike Parsons as demonstrating the shift in Aboriginal tourism from “presenting culture as an object… to culture as a subject”.

Scenes from the opening of the Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Centre, which Inside Out Architects designed to support and encourage existing living practices, etiquette and knowledge systems. The centre is described by Mike Parsons as demonstrating the shift in Aboriginal tourism from “presenting culture as an object… to culture as a subject”.

Scenes from the opening of the Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Centre, which Inside Out Architects designed to support and encourage existing living practices, etiquette and knowledge systems. The centre is described by Mike Parsons as demonstrating the shift in Aboriginal tourism from “presenting culture as an object… to culture as a subject”.

Architectural interpretations of Aboriginal identity in the design of cultural centres, museums, keeping places, art centres and other buildings play an important role in informing how the architectural profession, the Aboriginal clientele, and the broader public perceive Aboriginality. As anthropologist Francesca Merlan argues, Aboriginal cultural production, whether in art, architecture, or the establishment and/or maintenance of sacred sites, is closely entwined with non-Indigenous perceptions of Aboriginal people. As such, Aboriginal identity is not separate from external forces and influences, and architecture is one of these influences.

Many Australian architects have designed publicly accessible buildings which incorporate Aboriginal cultural references and symbolism – for example Peter Myers’ Tiwi Museum on Bathurst Island, Paul Memmott and Will Marcus’s proposal for Carnavon Gorge Aboriginal Museum, projects by Merrima Design Group NSW Government, the Brambuk and Uluru Kata Tjuta cultural centres by Greg Burgess, the National Museum in Canberra by Ashton Raggatt McDougall, and Karijini National Park Visitor Centre by Woodhead International BDH, among others. All of these projects use abstractions of Aboriginal ancestral histories or environmental relationships as a medium to represent Aboriginal identity in building design.

There is also an established body of writing about this architecture containing representations and abstractions of ideas of Aboriginality (authors include Paul Memmott, Kim Dovey, Mathilde Lochert, Rory Spence, Cathy Keyes, Joe Reser, Catherine Chambers, Mike Austin and myself). In contrast, this essay draws on another emerging body of built work to explore architectural processes and projects that might imbue architecture with Aboriginal identity through client involvement and authorization, through respecting Aboriginal social practices and revering existing places and histories, without attempting to abstract them into semiotic devices in form, plan or section. Three issues are pertinent here, which have had minimal coverage in architectural literature to date: the importance of leaving ancestors in the country; Aboriginal custodianship and/or identity with ancestors, places and designs; and, Aboriginal identity first through occupation and then through representation.

Aboriginal place making and architecture. In traditional Aboriginal mytheopia and place-making an understanding of the relationship between an ancestor and a place – developed through learning verbal and graphic stories, songs and dances – is necessary before one can read an ancestor in a place (usually in the natural landscape). For example, in north-east Arnhem Land a low rock formation projecting from the ground might be a remnant of the travels of an ancestral shark, but unless one is privy to such information, the qualities of the shark cannot be seen in the geological formation. It is also important to note, however, that new Aboriginal places of cultural significance are made through the occupation and use of a place over time without necessarily containing references to an ancestor or ancestral history, and that some places “come to be known” by Aboriginal people through their physical characteristics or likeness to a particular ancestor. For example, the literature on the Brambuk Living Cultural Centre suggests that Aboriginal users and clients of the facility have “seen” a range of ancestors, including cockatoos, eagles, and whales, in its physical form without them being purposefully designed into the building.

Over the past ten years, a small group of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australian architects have been producing architecture that avoids the iconic representation of Aboriginal ancestors or references to “The Dreamtime” and pursues different approaches to the question of identity and architecture. This work includes Merrima’s Wilcannia Health Service Project, which, although drawing references from the Darling River and its sacredness to Barkanji people, does not obviously abstract any Barkanji ancestors. Other projects – such as the Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Cultural and Civic Centre, by Inside Out Architects, and the proposal for the Musgrave Park Culture Centre, by Richard Kirk and Innovarchi – project the built environment as complementary but acquiescent to the social and political history of the Aboriginal people who use the buildings and to the significance of the places in which the buildings sit. In this manner, Mike Parsons argues that the Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Cultural and Civic Centre demonstrates a shift in emphasis in Aboriginal tourism from “presenting culture as an object… to culture as a subject”, in which the static presentation of Aboriginal objects and history is superseded by the daily events and activities of Aboriginal people.

Leaving ancestors in the country. The significant meaning of Aboriginal places traditionally comes from their occupation and creation by ancestors, and their use and recognition by Aboriginal people over time. In a context in which a building is constructed adjacent to a significant site imbued by an ancestor, does the ancestor really need to be reproduced in a remnant or abstraction in the building? If the answer is yes, who does the building re-present the ancestor to? Surely not to the Aboriginal clients who already know and understand the ancestor’s existence in country? As Paul Memmott has pointed out, public buildings such as art/cultural/interpretive centres are created not only for the local Aboriginal users, but also for local non-Indigenous users, Aboriginal people from other areas, and non-Indigenous visitors – including international travellers. How, and by whom, should the complexities of Aboriginal culture and history be interpreted for this broader public?

While working with Yolngu people in Arnhem Land between 1997 and 2002 I found that some client groups specifically wanted to avoid any reference to Yolngu ancestral histories in the design of buildings because they saw non-Indigenous architecture as just that – a non-Indigenous initiative or imposition. These groups felt that ancestors and their histories were best left in the country. Similarly, Aboriginal architectural graduate and writer Carroll Go-Sam comments that “story places of ancestors are about country, divisions, boundaries, ownership and being caretakers for country – if you put it in a building it is disenfranchised”. Tania Dennis experienced a similar response while working on the Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Centre, which she likens to “a blank canvas” – a backdrop for the art and activities exhibited. The clients and steering committee for this project specifically stated that they had no interest in incorporating references to ancestral beings (or curvilinear forms) in the design.

This rejection by Aboriginal clients of picturing Aboriginal identity in built environments through ancestral references might be seen as a desire to embrace cultural maintenance through occupation and ownership, rather than through cultural branding; and to avoid conflict over identity and custodianship of ancestors and their histories.

Whose ancestor, whose design? One of the issues often raised in discussions on design projects with Aboriginal groups is not whether to represent ancestors, but which ancestor or history to choose. Client groups are regularly comprised of different peoples who have different connections to places, histories and ancestors; hence the ancestors, stories and designs associated with particular peoples are not always appropriate for the entire group. The problem with applying iconic representations of ancestral beings to architecture and design is partly related to Aboriginal kinship and politics. When an Aboriginal ancestor or their remnants is depicted in the design of something – object, building or settlement plan – the group of people closely associated with that ancestor may claim custodianship over the design because it is an integral part of their identity. As anthropologist Peter Sutton observes, “Designs [as evident in Aboriginal art] are not public property. Ancestral Beings, Dreamings, gave them for certain groups to hold in trust. Infringements of this copyright are in some places still met with vigorously applied sanctions.” ›› Anthropologists Nancy Williams, Ian Keen and Howard Morphy also demonstrate how ancestral stories, places and designs have dynamic custodianship which can change over time: a story, place, or design associated with a particular ancestor and Aboriginal group can be incorporated into the identity of a different but related group.

Hence, if a building contains representations of a particular ancestor and their story, but has many different Aboriginal users, political problems may occur related to the use and assumed identity of a building.

Having said this, Aboriginal groups who have suffered dispossession will often endorse the use of ancestral imagery in architectural design as recognition of their group Aboriginal identity. For example, on a recent project at Palm Island, on which I worked with members of the Department of Housing’s Community Renewal Program, the client group was keen to use imagery of the sea and of green sea turtles in the design of a new youth facility. The green sea turtle was seen as a unifying symbol for the client group not because of their connection to the story of the turtle and its place making, but because the turtle was one of their favourite foods. If the food of a particular client or user group is an adequate symbol from which to generate a design idea for a non-food related facility, what difference is there in deriving an idea from any other commonly held symbol? Although there might be problems associated with custodianship and authority in using a particular symbolic reference in a building, another consideration should be the flexibility of ownership and use of a building over time. If architecture contains obvious cultural references or abstractions, its reuse is immediately affected by its “built-in” identity.

Of course I am not suggesting that buildings that do not interpret or represent Aboriginal identity in direct ways are free of cultural associations and shackles; they are imbued with the technology, space and aesthetic of the culture (and architect) through which they are developed. As Mike Austin observes, when writing about the Tjibaou Culture Centre in New Caledonia by Renzo Piano, “Every contemporary construction has formal origins deriving from western building (whether acknowledged or not) and the denial of an international formal language is to deny the architecture of the building.” However, to layer a cultural brand, such as an abstracted symbol of an ancestor, over western technology and aesthetic without attending to the broader issues of Aboriginal custodianship and occupation is to pay lip-service to the richness of Aboriginal culture, its maintenance and persistence.

Identity through occupation first, representation later. In making contemporary Aboriginal architecture, new places containing Aboriginal identity are created which did not exist prior to their design, construction and occupation. Whether a place has recognized cultural significance as an existing sacred ancestral site or whether it has cultural significance as a place newly constructed from other shared histories and identities – such as a cultural centre – the process of place recognition necessitates that its meanings must be socially constructed through a continuity of practices over time.

The idea of “place transfer”, developed by Paul Memmott, is one example of how place recognition can occur in new Aboriginal architecture. This occurs when the physical and spiritual qualities of one place are invoked and applied to another spatial context, effectively creating the first place (or a memory of it) in the second location. This can occur either through activities and events undertaken by Aboriginal people, or through the incorporation of objects or symbols pertaining to Aboriginal culture.

Place transfer is an important quality of ceremony grounds in contemporary Yolngu settlements in Arnhem Land; it allows people to summon their social identity and history even when they are distant from their ancestral homeland. During the enactment of ceremony, practices such as dancing, playing music, and creating ground sculptures represent ancestral places and powers, and the ground becomes a referent for another distant place such as an ancestral homeland or tract of country. For example, art curator Djon Mundine explains that ground sculptures that are recreated in foreign environments for art exhibitions, are “…spiritual embassies, in that they represent specific landscapes and can be constructed in any appropriate place where a ritual performance might be needed. Moreover there is usually no need to use soil from the home country. Once such specially created sites are sung over, they ‘become’ that place symbolically, until destroyed by being danced over at the conclusion of the ceremony. Their context may well be inside a building, in an urban setting, or even a foreign land.” ›› Ceremony is not the only mode of place transfer, but it is a useful example of an ongoing cultural practice which give new places meaning and significance. Daily activities such as meeting, talking, sitting, yarning, playing, working, painting and cooking are also processes that imbue a place with meaning and culture associated with the user group. The Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Centre at Warburton was specifically designed to support and encourage existing Aboriginal living practices, as well as kin-related Aboriginal etiquette and respect for the layering of Aboriginal knowledge systems. The former manifests in a flexibility of space which avoids a linear progression through the architecture enabling easy entry and exit, and the latter in preventing unwanted intrusion into particular parts of the centre through the layering of spaces from public to private, or secular to secret.

Conclusion. In discussing the topic of representing Aboriginal identity in architecture I have raised more questions than I have answered. It is a complex and controversial subject to be approached through a brief article by a non-Indigenous person. Nonetheless, these are important issues which are well worth pursuing further.

The impetus for this essay came from emerging approaches to Aboriginal projects which purposefully avoid the inclusion of Aboriginal ancestors and mythology as design generators. As I have suggested, they draw their Aboriginality from their support of Aboriginal social practices in the occupation, use and management of the facility, and, although juxtaposed near places of cultural significance, they opt to leave the sacredness of the place in the landscape and its associated history.

Designers are often called upon to imagine new possibilities, and when that happens they act as cultural critics and as promoters of culture change. In the design of art, culture and interpretive centres, keeping places and museums, architects contribute to changing where and how significant meanings in Aboriginal places are created, and to Aboriginal cultural production. As such, architects and designers need to have an understanding of the complexities involved in the use of abstracted metaphors and encryptions from Aboriginal culture into architecture which is mostly derived from the architect’s own cultural milieu. The few projects discussed here seem to indicate a move in Aboriginal cultural production which recognizes that the significance of Aboriginal ancestors, their representation and custodianship, and that cultural maintenance and continuity are more pervasive through activity than image.

Shaneen Fantin has recently been awarded a PHD from the University of Queensland for her research into aboriginal living environments in Arnhem land. at the time of writing she was a lecturer in architecture at the University of South Australia. she would like to thank the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre, Carroll Go-Sam, Tania Dennis, Richard Kirk and Stephanie Smith for their contributions to the development of this essay.

Images: Mike Gillam, Eye Saw Studios

Select Bibiography

Mike Austin, “The Tjibaou Culture Centre” Pander 8 (Winter 1999).

Kim Dovey, “Architecture for Aborigines” Architecture Australia vol 85 no 4 (July-August 1996) pp. 98-103.

Shaneen Fantin, Housing Aboriginal Culture in North-east Arnhem Land, PhD thesis, Aboriginal Environments Research Centre, University of Queensland, 2003.

Shaneen Fantin, “Recognising Aboriginal Architecture from North-east Arnhem Land” Additions SAHANZ Conference Proceedings, Brisbane 2002.

Cathy Keys, “Warlpiri Ethno-Architecture and Applied Aboriginal Architectural Design: Case study material from Yuendumu” PaPER 55-56, pp. 54-68.

Mathilde Lochert, “Mediating Aboriginal Architecture” Transition 54-55 (1997) pp. 8-19.

Paul Memmott, “Aboriginal Signs and Architectural Meanings” Architectural Theory Review 1 (1997) pp. 38-64.

Paul Memmott and Catherine Chambers, “Spatial Behaviour and Spatial Planning at Galiwin’ku: New insights into Aboriginal housing” Architectural Review Australia, Residential 02, pp. 88-97.

Paul Memmott and Stephen Long, “The Significance of Indigenous Place Knowledge to Australian Cultural Heritage” Indigenous

Law Bulletin, vol 4 no 16 (1998) pp. 9-13.

Paul Memmott and Joe Reser, “Design Concepts and Processes for Public Aboriginal Architecture” in PaPER 55-56 (2000) pp. 69-86.

Francesca Merlan, Caging the Rainbow: Places, Politics, and Aborigines in a North Australian Town (University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 1998).

Djon Mundine, “The Native Born” in B. Murphy (ed) The Native Born: Objects and Representations from Ramingining, Arnhem Land (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, in association with Bula’bula Arts, Ramingining).

Edward Relph, “Modernity and the Reclamation of Place” in D. Seamon (ed) Dwelling, Seeing and Designing: Toward a phenomenological ecology (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993).

Mike Parsons, Appreciating Indigenous Cultural Tourism: the cultivation of the symbolic landscape in response to a demand from a non-traditional market.

J.W. Robinson, “Architecture as a Medium for Culture: Public institution and private house” in M. Setha and E. Chambers (eds), Housing, Culture & Design: A Comparative Perspective (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989).

Rory Spence, “Brambuk Living Cultural Centre” The Architectural Review vol 184 no 1100 (October 1988) pp. 88-89.

Peter Sutton, Dreamings: the art of Aboriginal Australia, (New York: Viking Press, 1988).

Franca Tamisari, “The Meaning of the Steps is in Between: Dancing and the curse of compliments” The Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol 11 no 3 (2000) pp. 274-286.

Nancy Williams, The Yolngu and their Land: A system of land tenure and the fight for its recognition (California: Stanford University Press, 1986).

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2003

Words:

Shaneen Fantin

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2003