Review Andrew Nimmo

Photography Peter Bennetts, Ben Wrigley

Individual holding dens for the pandas are located behind the public viewing area in the panda holding building.

View across the entry forecourt, with the conservation building to the left and the entry building to the right.

The open ticketing area leads under the entry building into the zoo.

View from the orientation zone inside the zoo back toward the entry building.

At the eastern corner of the entry building, angled glazing reveals the green wall and stair inside.

The green wall on the stair leading to the long gallery on the first floor of the entry building.

The curved exterior of the entry building fronts the forecourt, with ticketing and retail at ground level.

View back toward the forecourt from the western end of the entry building. At left, a green roof extends from the conference space on the first floor.

The first floor of the entry building houses the long gallery and a conference space.

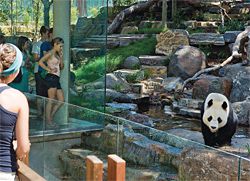

The sheltered public viewing area is located at the front of the panda holding building.

Under the bamboo canopy, glazed viewing areas show the pandas at rest.

There is a certain excitement in the air at the Adelaide Zoo. Wang Wang’s testes have dropped. This is big news in the difficult world of panda captive breeding. It is not hard to understand why these ridiculously cute mammals are endangered – mature pandas are sexually active for only two to seven days a year. So opportunities for hitching up in the wild, where habitat has been declining for thousands of years, are limited. A lot is now resting on the arranged courtship of Wang Wang and partner Funi, and architecture is playing its part. Their new enclosure has to perform three fundamental roles: replicate as closely as possible conditions in the wild; provide for extensive but noninvasive public viewing; and allow for round-the-clock monitoring through the constant examination of blood, urine, faeces, et cetera.

In designing the enclosure, Hassell has not sought to hide the less cuddly aspects of panda care – the examination holding pens are deliberately pushed front and centre of the main public viewing area. Each panda has its own enclosure – they only come together for procreation, so everything is duplicated. Attempts to mitigate the hot and dry Adelaide summer are based on through water-cooled artificial rocks and large airconditioned glass-fronted day rooms. The enclosure and associated gardens also contain inevitable references to the pandas’ homeland, some less subtle than others, but the overall impression is more regional than cultural.

Pandas are the pop stars of the zoological world. When Alexander Downer helped secure a pair of pandas on long-term loan from the People’s Republic of China in 2007 for the Adelaide Zoo, the first in the southern hemisphere, it was a major coup. The sheer importance of the animals meant that the panda enclosure got everything it needed in terms of brief and budget. Not surprisingly, it is well considered, well detailed and well funded. It captures the zoo’s message of animal welfare and biodiversity, while providing a satisfying viewing experience for the paying public. However, the arrival of the pandas also had a significant impact on the rest of the zoo, as it had to prepare for the inevitable increase in visitor numbers.

Pandas became the generators for a range of ancillary projects that were able to tag onto the funding stream. It is these other works that probably provide the greatest public benefit.

Established in 1883, Adelaide Zoo is the only major zoo operated by a not-for-profit organization. As such, it had relied on an army of volunteers, bequests and fundraisers. That changed with the ambitious vision of CEO Dr Chris West, who arrived from London Zoo in 2006. West instigated a broader vision for Adelaide Zoo, with four key principles guiding all future activities: education, conservation, environment and research.

Located on the northern fringe of downtown Adelaide, the zoo shares boundaries with the River Torrens and the Botanical Gardens and has a frontage to Frome Road, site of the historic entry and gateway. The existing zoo was something of a fortress, with an opaque boundary keeping exotic animals in and non-paying eyes out. Long before the pandas arrived, the zoo had begun considering this physical interface with other municipal institutions and the public domain. In 2007, Hassell, which has a twenty-year association with the zoo, was engaged to prepare a framework plan. This identified important strategic moves to develop over time – transparent boundaries with the parkland setting, views into and out of the zoo, a new entry threshold facing back toward the Botanical Gardens and the city, and rejuvenation of First Creek. Each of these has been addressed in the recent works, including replacing 1.7 kilometres of copper log boundary with a transparent steel fence that reconnects the Zoological Park with its botanical neighbour and riverside park walk.

The existing heritage-listed entry gates were awkwardly located at a bend in Frome Road, and the public side was too tight to cater for large numbers of visitors assembling prior to opening. The new entry building, conservation centre and public forecourt realizes an early concept diagram from the framework plan, which shows a new entry portal with a deep threshold or “free zone” before the entry gates. (Although the historic gateway seems a little sad and lost now.) With its generous urban-scaled gateway portal, curving colonnade and solid masonry expression, the entry building commands the forecourt. One side contains ticketing, administration and cafe, the other houses the zoo shop and a lobby with stairs leading to the first-floor conference facilities. The stair terminates the eastern end in a sculptural flourish that showcases the hairy green wall within. A western terrace off the main conference room opens onto a green roof over the cafe that appears to gently fall away to the new approach and melt into the landscape. This is reinforced by another green wall to the southern side of the cafe, which leads pedestrians in from the street. Both green walls are having teething problems, but the zoo appears committed to them in the long term. On the other side of the forecourt, the conservation centre houses exhibition space and a theatre. A much more intimate building, it presents its own junior-scaled colonnade in folding steel clad blades.

The forecourt is made through a combination of building enclosure, the public language of colonnade forms, and a clear understanding of pedestrian desire lines and framed views. The logic of the irregular plan only becomes clear through an understanding of the site. The building forms defer to the public domain and appear to be carved out by the movement of people. The result is a landscape-driven solution that illustrates a close collaboration between the various divisions within Hassell.

The zoo side of the entry building has a totally different expression – vertical timber blades extend across the entire facade as a giant screen, acknowledging the changing role of the building from civic front to landscape enclosure.

The disciplined materials palette revolves around different expressions of concrete (off-form, polished, precast), timber (spotted gum battens, large-section external seating, internal timber veneer lining), metal (cladding and roofing) and sheer frameless glass. At times this has been busied up by the interior design department, but mostly it stays on message.

Public projects should be a catalyst for urban repair work. The brief presented to Hassell was aspirational rather than specific, allowing the practice to realize the aims of the framework plan. Some of this work extended beyond the zoo boundaries and required cooperation from the Botanical Gardens and other agencies. Cadastral boundaries do not always reinforce sound urban design. Here the various agencies put aside their territorial instincts and successfully worked together to complete the work beyond the legal boundaries of the zoo – realigning the road and bus park as well as returning 2,000 square metres of zoo land to public use as the entry forecourt.

In South Australia, the project is understood as an example of integrated design, as espoused by 2009 Thinker-in-Residence Professor Laura Lee (now the new Commissioner of the Integrated Design Commission). Among other things, the aim is to get the many agencies of government and industry to work together to realize the potential of the spaces in between.

The architecture and forecourt design is at times a little overworked and perhaps too ambitious for its modest scale, but the enthusiasm is a pleasant diversion from the steady-as-she-goes architecture that is the norm in Adelaide. This project, along with recent additions to UniSA, completed in association with John Wardle Architects sets important new benchmarks for the city in considering the public interface of buildings.

Andrew Nimmo is a director of Lahz Nimmo Architects.

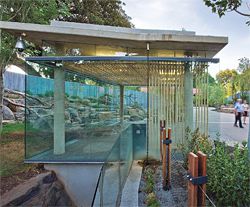

Sliding bamboo screens enclose the public viewing area when required.

A viewing pavilion at the western edge of the public space accesses one of the outdoor panda exhibits.

The pavilion is constructed from glass, concrete and bamboo.

The new panda holding building houses three holding dens and a nursery.

The keepers’ office has direct access to the holding pens, bamboo store and preparation kitchen.

Detail of a holding den with resident panda.

ADELAIDE ZOO ENTRANCE PRECINCT AND GIANT PANDA BAMBOO FOREST

Architect

Hassell— project director Mariano DeDuonni; design architect/project team leader Timothy Horton; project team Sharon Mackay, Alex Hall, Nicholas Pearson, Ed Mitchell, Hugh Fraser, Josh Palmer, Maciek Furmanik, Andrew Schunke, Sam Wee, Meaghan Williams, David Bills, Amy Reed, Susie Nicolai; project architect Timothy Horton, Alex Hall; landscape architect team leader Sharon Mackay; senior landscape architect Nicholas Pearson; interior design team leader Andrew Schunke; horticulture Amy Reed; senior graphic designer Susie Nicolai; planning David Bills.

Project management

Arup.

Structural and civil engineer

Wallbridge & Gilbert.

Mechanical, electrical, hydraulic and fire engineer

BESTEC.

Access consultant

Disability Consultancy Services.

Quantity surveyor

Rider Levitt Bucknall.

Acoustic consultant

Sonus.

Water features

Waterforms International.

Green roof and walls

Planning SA—Graeme Hopkins; Zoos SA—Jeff Lugg.

BCA consultant

Katnich Dodd.

Construction team

Managing contractor—Hindmarsh.

Photography credits

Peter Bennetts 2-10, 12. Ben Wrigley 1, 11, 13-17.