I live and work in Mparntwe, or Alice Springs, in the Northern Territory, which is a town with edges. The edges I have in mind are not spatial constructs but rather the multiple levels and types of anxiety that operate in the social fabric of the town.

Town residents not born and bred in Alice Springs are essentially an expatriate community. They come for six months, twelve months, three years or even a full career, but all of them, always and at some level, have an exit plan. This “foot to the door” mentality manifests as a persistent anxiety that pervades our lives, producing a profoundly different experience of place to that of someone born in the town – those who are centred there for many and varied reasons, from cultural ties and obligations, a profound relationship with the land and kinship networks to poverty and lack of opportunity.

These two communities occupy the same space but seem to operate in different universes. Except for rare interactions, the groups mind their own business and get on with their own activities. This well-established separation appears to follow a set of tacit rules – a level of civility and cooperation that sits strangely in the context of this rich, stimulating, frustrating and exhausting town.

Strangely enough, it is an English novel that provides insight into this urban condition. The City and The City by China Miéville is a detective novel with a science-fiction twist. The detective story takes place in a fictional European city. This setting is in fact two cities that occupy the same space simultaneously. The citizens of each city walk many of the same streets and drive on the same roads, but are trained from early childhood to recognize the “other” city and to immediately “unsee” it along with all its elements and citizens.

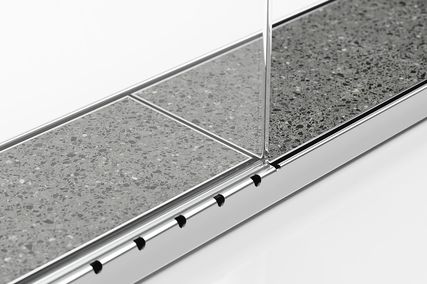

The Alice Springs CBD Revitalisation (2013) broaches the edge between the “two towns” of Alice Springs. The project reconnects the CBD to the culturally significant Todd River with an open and visually unobstructive design.

Image: Brendan Chan

This paradigm has an immediate resonance with conditions in Alice Springs. There are at least two towns operating here, and they can predictably be divided into the Indigenous town and the non-Indigenous town. There is a surprisingly low level of integration, or joint participation, between the two towns of Alice Springs, with some notable exceptions, one of which is sport.

Architectural practice is an activity centred firmly in the non-Indigenous town, however, as professionals who engage in the production of physical environments, there are opportunities for us to shape both environments. Three of our recent projects can be used to illustrate this two-town paradigm.

The first, MPH HQ, occupies space and functions mainly in the non-Indigenous town. It is a large work shed and office for a local building contractor.

The site for the project is a prominent corner in a light industrial area that is already developed with work sites and the type of retailers who need a large amount of inexpensive space – tyre fitters and bedding and plumbing retailers, for example. The existing development in the area is the depressingly familiar off-the-shelf industrial shed with a small, often two-storey office and retail section at the front – a form common to light industrial precincts and highway strips across the country.

In our project, an off-the-shelf industrial shed aligns with one street boundary and a leftover wedge of land is used to provide the finer-grained space needed for reception, office and staff facilities. Office functions are placed on the upper level to take advantage of great views and large enveloping sunhoods are designed to exclude 99 percent of direct sun from a problematic south-south-west aspect. The big shed operates as a dynamic space that changes from day to day as materials and vehicles for worksites come and go.

This building appears quite different to the other commercial premises on the street, but is essentially the same building type working harder to achieve more amenity, comfort, sustainability and aesthetic value for the street and the owner’s business profile.

This project operates mainly within the non-Indigenous town. It achieves some reasonable architectural aims and is a solid citizen in its own town, but does not offer much to the other town. In that respect, the citizens of the Indigenous town probably “unsee” this building.

The ASTC Cemetary Chapel (2018) is a place where the lives and cultures of people in “both towns” of Alice Springs converge. Large sliding doors allow the space to be transformed into an expansive one-room pavilion.

Image: Gary Annett

The second project – the ASTC Garden Cemetery Chapel – is a place where the lives and cultures of people in both towns converge. The chapel is a non-denominational space for the community of Alice Springs, and is open to all religions and types of ceremonies.

The chapel is designed to act as a one-room open pavilion or a one-room enclosed space, depending on weather conditions. Six large doors of multicell polycarbonate can slide away to connect the interior to the verandah with a 13m column-free opening, more than doubling the seating capacity.

It is not uncommon that a funeral for a significant person in Alice Springs is attended by more than 1,000 people. Because of this, the chapel verandah adjoins a wide grassy area with a low-relief mound to its perimeter that can seat an unspecified number of additional people, while also providing a place for kids to cut loose and play. This connection to the exterior landscape provides a level of comfort and ease that does not predicate a particular type of service or cultural protocol, allowing the chapel to engage, to some extent, with the lives and cultural contexts of both towns.

In the third project – the Alice Springs CBD Revitalization – we consciously aimed for a strong engagement in both towns in order to create places that have layered meanings and provide wide functional benefit.

The project reopens part of the town’s central mall to traffic and establishes stronger connections between the CBD and the Todd River, which defines the eastern edge of the CBD. The river, dry for most of the year, is a beautiful natural feature with strong Indigenous cultural values.

Arrernte custodian Doris Stuart and local artist/photographer Mike Gillam were commissioned to map out a cultural framework for the project. Their proposal for a biodiversity corridor provided a way of highlighting cultural links between the CBD and the river. The biodiversity theme was most strongly expressed in the design by opening up sight lines between a significant and imposing river red gum in Parsons Street and a stand of sister trees at the river’s edge.

We deliberately created poetic names for areas of the project to try to strengthen community engagement and add cultural depth. We hoped these names – the Rainwater Reflection Pan, The Caterpillar Seats, the Cascade Feature and the Riverbank Garden – would gain currency in the public realm and provide a key to the stories and culture that generated the design features.

These design elements serve a range of functions, providing graphic demonstrations of the seasonal presence of water and references to flora and fauna. The moth-inspired shade structures are an indirect reference to the Yeperenye Caterpillar, one of the three dreamtime caterpillars who created the striking MacDonnell Ranges that flank the town.

This two-town analogy is, of course, a gross oversimplification of a complex urban social fabric. There are many more towns if you choose to see them, including tourists and young people, who are a town unto themselves. What is the point of talking about two towns? Why not just talk about Indigenous and non-Indigenous people occupying the same space?

Others might argue that the two-town analogy does nothing more than point out differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people’s lives that everyone is already aware of in outline, if not in detail: statistically Indigenous Australians are poorer, have a lower life expectancy and level of education and experience astronomically higher levels of incarceration than non-Indigenous Australians. Non-Indigenous Australians are all displaced peoples of one sort or another, lacking the longstanding culture and connection to land of Indigenous peoples and forever connected to a rapacious colonial past and its associated burden of guilt.

An architect can feel pretty ineffectual when designing within this value-laden space. We are assigned or adopt our roles as rescuers and rescued, and the perceived problems continue, decade after decade.

However, these descriptors of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are comparative or made by association, and risk defining Indigenous people by their disadvantage, and defining non-Indigenous people by a historic debt. These issues are important and must be recognized, but do not provide a constructive framework for architects and others working with the contemporary built environment. The two-town analogy provides a way of framing the contemporary world that is not value-laden, and recognizes that people are living their own lives, centred in their own personal experience and cultures, and are not to be defined by comparison.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 22 May 2019

Words:

Sue Dugdale

Images:

Brendan Chan,

Gary Annett,

Peter Barnes

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2019