Panorama from behind the site, looking towards the bay with the operations building (yellow) and sleeping and medical quarters (green). Image: Adrian Young, AAD.

The competition-winning scheme. Piloti were determined to be ideal for reducing snowdrift. Image: Paul Owen, AJC.

Photomontage showing the current scheme on site. Image: Tomas O’Malley, AJC.

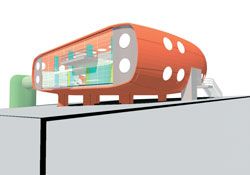

External perspective of current scheme. Image: Tomas O’Malley, AJC.

View from the lounge to the bar below. The interior has been designed to provide spaces with differing levels of intimacy to accommodate the large fluctuations in occupant numbers. Image: Tomas O’Malley, AJC.

Architect Michael Heenan wind tunnel testing the final design. Image: Nic Bailey, AJC.

For many architects, Allen Jack + Cottier’s project for new living quarters at the Australian Antarctic Division’s (AAD) Davis Station will appear to be like one of Robert Venturi’s generic sheds painted red. However, appearances are deceiving, and such a glib description of this building would miss the point entirely. In fact, this project, examined beyond its red Esky-like exterior, highlights the way architects are able to use architectural design to create innovations in building. Buildings in extreme or hostile environments have a long tradition in architectural design, and play a key role in architectural imagination. During the 1960s, for example, avant-garde architects produced proposals for habitats and colonies in and on oceans, deserts, icecaps, outer space, and even the moon. Architects as diverse as Archigram, Frei Otto, Buckminster Fuller, Paolo Soleri, Paul Maymont, Ralph Erskine, and the Japanese Metabolists all proposed schemes for extreme environments. In these projects architects bravely mixed together new construction technologies with the utopian. Following the oil crisis in the early seventies, and the concurrent rise of postmodernism, architects retreated from such approaches – approaches which were criticized as being either excessively utopian or too closely aligned with corporate late modernism. As a result, the link between architecture and technology, in avant-garde practice at any rate, was severed. The loss to architecture is now palpable as architects attempt to recover ground once forsaken.

Nowadays, technology and utopia are once again back on the architectural agenda. This project, while more practical than utopian, serves, nonetheless, as a case study of successful technology innovation as a result of a focused architectural design process.

Allen Jack + Cottier’s project serves to remind us that architects are skilled at finding solutions to problems that account for environmental context, human behaviour, construction methods, and aesthetics. The first layer of issues that required innovative design was related to the project’s location. Davis Station is situated on Prydz Bay, just east of the Amery Ice Shelf near the Vestfold Hills in Antarctica. It would be wrong to presume that this is a bleak white landscape of climatic white noise without topography and history. The Vestfold Hills are, themselves, 400 square kilometres of bare low hills dotted with lakes and tarns. This area of the world is quaintly called Princess Elizabeth Land. Mawson flew over it in 1931 and in the mid-1930s Norwegian whalers landed nearby. Davis itself is named after the mariner Captain John King Davis, a Sydney Grammar boy who made numerous voyages to the Antarctic before World War I.

The design of these living quarters has had to take into account the extreme environment of this remote place. Wind velocity can reach 324 kilometres per hour and temperatures range upwards from minus 40 degrees Celsius, rarely rising above 5 degrees Celsius. Based on these factors, the design process began with the formulation of performance criteria. This included researching the best types of new materials that could withstand such extremes. Architects Michael Heenan and Nicola Middleton then proposed various building configurations aimed at reducing snowdrift and tested these shapes in a flow visualization tank (a precursor to wind tunnel testing) to help predict snow deposition around the building. The ideal configuration was determined to be a building on piloti, but the client in the end preferred the building on the ground.

Nonetheless, the observations gained from the testing were used to optimize the building’s orientation and shape. In parallel, the architects had to design the building in response to the fluctuations in the station’s resident population. This can range from thirty people, in winter, to a hundred people in summer. To deal with this, the architects have designed a series of flexible internal spaces, which provide the occupants with different levels of intimacy. This is achieved through the prudent use of materials and textures.

From the beginning, construction materials and sequences were an important consideration in the design process. The building needed to be made in Australia and then shipped to the Antarctic. Using the performance criteria as a benchmark, the architects researched possible construction materials and methods. In particular, they drew on the construction of fibre composite yacht hulls. As a result, the walls of the building are 200 millimetres thick. They provide insulation to the occupants, while the fibre composite construction also allows uneven structural loads to be accommodated through the particular laminates of the structure. The walls are built one layer at a time and cast into panels. The first layer put into the mould is the exterior vermilion-coloured gel coat – a colour that accords with the AAD’s colour-coding of Antarctic stations. Each moulded panel is then vacuum-sealed in a bag and baked in an oven to ensure chemical bonding of the layers. The multiple layers of fibreglass, or carbon in some cases where strength is needed, will surround a core material of either balsawood or insulating Styrofoam.

The key to solving many of these issues was the decision to design and build a section of the building as a prototype. This was done because the 2.4 x 8 metre panels need to be erected at Davis after shipping. At Davis, the building’s panels will be literally glued together, so shipping costs and erection times are critical. Again, this echoes the 1960s, when architects dreamed of expressing growth, change and mobility by the use of prefabricated building systems and components. The work of Archigram is the best example of this: Peter Cook’s Plug-in City, Ron Herron’s Walking City and David Greene’s Living Pod all exemplify the hopes of human mobility – and freedom – enabled by prefabrication. Archigram were strong advocates of architects building prototypes. The Architectural Association, where Archigram taught in the late 1960s, was awash with prototype domes, bubbles, and instant cities in miniature. Prototyping, as this project indicates, is an essential part of the architectural design process – even architectural drawings and diagrams are prototypical – and is a technique that allows emerging innovations to be tested.

The innovations in this building attest to the fact that architects know how to innovate with foresight. All architects are taught in architectural design studios how to innovate in ways which seem at odds with more sequential, linear and modular models of innovation. (It is remiss that more innovation theory is not taught in the architecture schools.) On graduating, architects gain experience in innovation because most architectural projects are the result of many small incremental changes and innovations.

Such incremental innovation typically results from assembling something in a different context to make it faster, cheaper or better looking. Occasionally, more radical innovation is required. Radical innovation, as is the case here, is often driven by a complex mix of precedent and external drivers – the architects of this building have gone well beyond the boat-building precedents that were their initial inspiration. The innovations in this project are the result of the architects simultaneously researching, developing and integrating multiple design streams. Consequently, the project points to the fact that architects, with strong client support, are uniquely positioned to use research and development in the architectural design process to drive innovation.

Peter Raisbeck is a PHD Candidate in Architecture at the University of Melbourne and currently provides innovation and strategy advice to design orientated.

Credits

- Project

- Davis Station living quarters

- Architect

- Allen Jack + Cottier Architects

Chippendale, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Michael Heenan, Nicola Middleton, Samantha Taylor, Ben List, Mark Corbet, Bevin Page, Fergus Cumming, Paul Owen, Jenny Min, Nerida Bohringer

- Consultants

-

3D designer

Tomas O’Malley

Acoustic engineer Ask Acoustics & Air Quality

Composite design Jutson Yacht Design

Composite materials advisors ATL Composites

Initial competition consultants Hyder Consulting, Boatspeed Australia, ATL Composites

Insulation/fibreglass Thompson Fibreglass

Kitchen consultant Createring

Quantity surveyor WT Partnership

Services engineer SEMF Pty Ltd

Structural engineer Hyder Consulting

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

- Client

-

Client name

Department of Environment and Heritage, Australian Antarctic Division.