<b>REVIEW</b> DOUG NEALE <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> RICHARD STRINGER

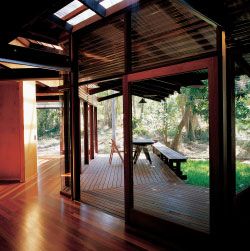

Rex Addison’s speculative house in Taringa. Looking from the living/dining area to the study and verandah.

Overview of the O’Rorke-Graham House from the north-east.

The Taringa House. View from study across to the verandah and living/dining areas.

The Taringa House. The living room bay window, the bathroom and the landing seen from the verandah.

The Taringa House. Entry on the half level. Stairs lead up to bedrooms and down to living room.

The Taringa House. South elevation to the driveway.

The Taringa House. North elevation to the garden.

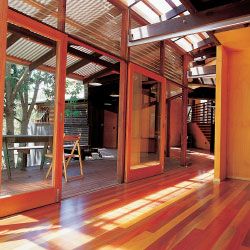

The O’Rorke-Graham House. Looking east. The living area is in the foreground, with the main bedroom upstairs and the study/studio downstairs.

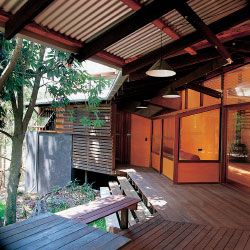

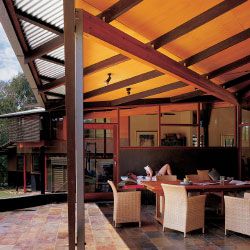

The O’Rorke-Graham House. The outdoor dining area.

The O’Rorke-Graham House. View over the dining room. The living spaces are each subtly affected by the shape and the character of the roof.

The O’Rorke-Graham House. South elevation showing the kitchen and dining window.

The O’Rorke-Graham House. Looking from the morning deck down to study and studio.

The O’Rorke-Graham House. The north-east wing, with bedroom upstairs and studio and study below. The morning deck is in the middle ground, with the living spaces beyond.

REX ADDISON’S INFLUENTIAL work is one of the sources of what has become known as the contemporary South-East Queensland “style”. In the September/October 2004 edition of Architecture Australia, Addison ruminated, by way of his idiosyncratic linocut print Homegame, on what form in architecture could have been had the Modern Movement never occurred. Readers may recall that Homegame is a precis of the sources and influences around which Addison’s own work turns and that it included an image of one of his recent houses.

This review concerns one subject of Homegame, the O’Rorke-Graham House, and another recently completed Brisbane house also designed by Addison – a speculative house sold as a self-funded, self-developed project. These two houses, completed within a few months of each other, are quite different in inception and outcome, yet they also have a certain coherence as the most recent refinements of a train of thought now thirty years in its evolution.

In the pages of architectural journals the inventive, “loose limbed” houses of Rex Addison are unmistakable. What marks this familiarity? In researching this piece I opened up the November 1986 edition of the UK’s The Architectural Review, with its survey of Addison’s work by the late Rory Spence. Here one can sense the beginnings of a dialogue between formal origins, by way of a regard for the “dignified” appropriateness of the local vernacular. In this work form making occurs through the development of a dominant roof figure and the plan is used both as a response to the consequences of roof configuration and, more importantly, as an opportunity to embellish the daily lives of the occupants. Such themes are in a kind of tension in this early work, which at times reads awkwardly. Over time this tension has relaxed, and the works exploring these themes have become more inventive without losing their consistency.

Some of the telltale plan geometries are present in these two recent houses. Both have similar plan configurations, derived from editing three roughly equal segments that arc in a 45 degree chamfered “L” toward the north and north-east. In both cases this geometric alignment to site is a response to specific but quite contrasting external factors.

In the speculative house, built on the last available portion of the land that accommodates Addison’s own residence and studio in the inner Brisbane suburb of Taringa, this strategy is a direct response to a number of difficult planning constraints on the approximately 500-metre-square battle axe allotment. The design not only accommodates setback and town planning regulations, it also avoids existing underground stormwater pipes and overland gully flow, preserves existing mature trees and provides privacy for the new and adjacent residents. In setting out the subdivision Addison has effectively organized the overland flow within setback requirements. The new site has a three-metre fall away from the approach easement towards the gully at the rear boundary. During the course of design development, several options were tested to overcome these myriad external constraints. Some of the more elegant solutions tended to reduce a potential connection with the ground in favour of a taller, more slender section. Mindful of height restrictions and the need to avoid an overbearing dominance in the gully, Addison resolved to maintain a two-level house that turned its back on his own, focusing attention to the existing trees as well as capturing north-easterly sun and breezes.

The resulting linear plan figure is broken into three segments to accommodate site and internal arrangements. The house proper consists of two of these segments; the third, the carport, fronts the easement. Located at the midpoint between levels, this third segment organizes arrival and circulation sequences.

A simple skillion defines the profile of the upper bedroom level, whose form is held back from the entry. The skillion appears detached from the “bones” of the house through some deft judgments in planning and construction. Reminiscent of the bedroom loft in Addison’s Taringa Parade House from the 1970s, the bedroom floor “floats” on a meticulously detailed hardwood and steel flitched bearer system, which also helps support the living level’s veranda roof. The upper, translucent portion of this roof presents the form of the bedroom level in three-dimensional relief, setting it apart from the surrounding enclosing elements while drawing light into the lower living areas.

The familiar Addison palette of hardwood frame, exterior and interior plywood cladding and lining, and corrugated roof sheeting is augmented by a bag-wiped block retaining wall to the west at the lower level. This stiffens the floor structure and supports the cantilevered bedroom corridor. An enfilade space, the corridor has its own roof, which defines it as a separate volume. This also reduces height to the west, lessening the bulk of building mass, and allows clerestory ventilation into the bedroom spaces. The ridge of the corridor roof establishes the set-out for the carport skillion, which is resolved into a gable that announces a larger entry volume at the half-landing.

Architectural expression is modestly maintained and reads as a direct account of the thinking behind the making. For example, the external frames and linings are carefully set out to provide a natural weathered profile and to reduce the use of costly and complicated trims and coverings. This in turn presents opportunities to use wall cavities imaginatively as space for storage, which reduces circulation dimensions. Many parts of the house have this quality of self-contained resolution. There is a quiet introversion as the house turns its back on its neighbours and finds its own place in the gully, while coping elegantly with the complexities of the taxing site geometry.

The O’Rorke-Graham House uses similar strategies to capture light and breezes through site placement. However, here the chamfered “L” plan is not due to constricted demands, but to a subtle judgment of landfall, siting and prospect.

The house, located on a one-hectare property in the established acreage suburb of Brookfield in Brisbane’s west, is designed for a family of four, including two teenage boys. It also provides office and studio/workshop facilities for the owners, one of whom is a conservator. Living spaces are generous and diverse, accommodating a complex array of family needs. As in Taringa, the land is the result of consolidation, being a portion of a five-hectare property recently re-parcelled. The allotment, typical of this area, is partly treed, with a dense group of eucalypts on its southern side. The larger remaining portion is cleared, being part of a turfed apron surrounding the original 1980s house.

A new driveway picks its way along the treed edge of the 1-in-17 ramping site to a slightly level grade. The house holds this tree line, opening out to the north-eastern cleared aspect. The original dwelling, located on the adjoining allotment, was used to cue the alignment of the short end of the final segment of the house, thereby reinforcing the sense of views opening up. This has the effect of conceptually placing the house in a kind of semirural idyll on the edge of clearing and forest.

The plan consists of two simple gabled bedroom pavilions held apart by a chain of living spaces. Although this is a much larger project than the Taringa house, the guiding dimensions of the principal room clusters are remarkably similar, a result of Addison’s view that grandness of programme is not an excuse to inflate the spatial norms of function. Roof pitches set at 15 degrees lend a gentle expansion to the internal volumes and provide flexibility in managing dimensional variants. In the western pavilion, bathroom spaces skew out of alignment with the passage, providing incident, privacy and threshold to the bedrooms adjacent. A variation of this strategy is also deployed in the eastern pavilion within the roof space of the carport.

The geometry of the centrally located living spaces turns counter to the frame of two larger intersecting roofs, which are supported by pairs of laminated beams that align their ridges with the wall plates of the bedroom pavilions. This removes the need for additional supports across these long spans. On plan, the chamfer terminates the junction of these ridges, presenting a large exaggerated gable with four openings to the uncleared eucalypts beyond. This central portion gathers up the social functions of the house under a dominant roof form, providing the family with two discrete realms accommodated by a shift in plan geometry provided by a half level change. This subtle adjustment in section allows this major plan element to maintain contact with the ground uphill, and at the same time permits access to the work areas downhill. The dominant roof drops its eaves to the north and lifts up to the south for daylight by way of the large gable. Translucent ridge vents with the Addison trademark of fretwork plywood panels transfer heat and filter light. The simple gables at each end of the segments join this more complex roof junction in a relaxed and elegant roof form that works as a counterpoint to the arcing of the house as it registers the ramping of the land. Daily life is literally and figuratively framed through the convergence of roof geometries.

The symbolic presence of “roof” and the celebration of everyday life has become the hallmark of Addison’s oeuvre. The roof as an archetype is returned to again and again. The opening quote, from P. J. Grillo’s Form Function and Design(Addison’s first year university textbook), has prompted the architect to allow the roof to fulfil the symbolic role of anchoring the life it frames. And it is this life that interests Addison the most. For him the task of the architect is to address life’s needs in a direct way, through attention to the brief and some of its more prosaic demands. For example, he is not shy, or apologetic, about desiring to provide “cosiness” in his work – a term now out of favour in certain architectural circles. In the O’Rorke-Graham House an evolutionary process of anchoring everyday needs with archetypal form continues. One might even say there is now more confidence and certainty of intention. An intention that embraces with clarity ethical and aesthetic concerns for landscape, an acknowledgment of the lessons of tradition, a registration of construction in the conduct of daily life, and an archetypal engagement with architectural form.

DOUG NEALE IS AN ARCHITECT AND ASSOCIATE LECTURER AT THE SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY PLANNING AND ARCHITECTURE, THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND.

Project Credits

Architect Addison Associates. Engineer Salmon McKeague Partnership— principal engineer Mani Salmon. Builder Lon Murphy.