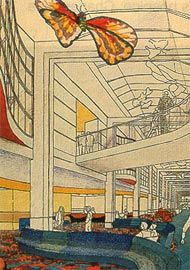

Sketch for the galleria at the New Children’s Hospital, Westmead, by Bligh Voller Nield.

Photograph of the galleria at the New Children’s Hospital.

The issue of the design of health buildings in Australia is a vexed one. The health landscape is littered with buildings of the 1960s and 70s – eight to ten floors of narrow ward floors stacked vertically on a podium accommodating diagnostic and treatment service. The majority of hospital building programs are in fact redevelopments of existing buildings, such as these, with some new bits stuck on. The decision to develop thus is driven by imperatives of the health dollar (ever shrinking), location (ideally wherever they currently stand), community concerns (don’t want to lose their hospital) and, more often than not, political gain (health is always an emotive voter issue). Whatever the motive, the strategy of redeveloping existing hospitals has inherent problems because the buildings of yesterday are simply not able to deliver today’s clinical services. For one or more of the reasons mentioned above, decision makers shy away from starting anew and therefore very few hospitals are being designed for greenfields sites. The real tragedy is that even these few lucky ones are, by and large, inept physical manifestations of functional health planning diagrams with little or no regard to an appropriate architecture or to site and context issues.

The reasons behind this sorry state of affairs are not hard to diagnose. Even with the best design intentions in the world, architects get overwhelmed by the sheer complexity and “hard” functional issues of a hospital brief. The process of hospital planning, onerous enough as it is, is further burdened by multi-layered management systems and convoluted hybrid procurement systems concentrated entirely on process rather than on the eventual product. But these issues, daunting in themselves, are not the only reasons for the unacceptable state of much hospital architecture. The real issue, in my opinion, is that little value is attached to the architectural quality of the hospital – to amenities such as natural light, views, wayfinding devices and public spaces. Instead, process-driven managers, under the guise of cost rationalisation, drive their obsession with statistics – area-per-bed, room areas, circulation percentages and so on – to such a level that they become the main criteria for the assessment of hospital design.

Although there is no doubt that the functional order is paramount in hospital buildings, designs driven entirely by the requirements of functional planning will produce layouts with convoluted, confusing circulation patterns. Architects, in an attempt to gain a market edge and win large projects, are getting themselves into a “health specialist” corner. This is not necessarily a bad thing. However, it is certainly a cause for concern when “specialisation” only embraces the technical knowledge of clinical functions and processes specific to healthcare, and does not include expertise in the resolution of the essential elements of architecture – light and shade, walls and space. This imbalance is often addressed by offering an association of two architectural practices – one for “health planning” and the other for “architectural design”. This is a dangerous situation; time and time again it has produced inept architecture, with “architectural” facades slapped on to clumsy internal layouts and cosmetically enhanced foyers as a token of “good design”.

Even in a functional sense, current hospital design does not respond adequately to changing clinical work practices. At best, some lukewarm attempts are made in a few areas, but the overall hospital building is still laid out in traditional configurations responding to outmoded models of care. In the current world of healthcare delivery it is simply not enough to tweak the edges of old typologies. Design responses must embrace all parts and aspects of the hospital. If the delivery of health services has changed radically, the buildings that dispense them also have to change. The new hospital will have to have a new form and structure. It will have to be a different monster – not only in terms of its form and layout, but also its physical fabric, circulation patterns, engineering services and structure. It must provide a seamless integration of clinical requirements with building planning and design issues. Established clinical practices have had to revise their approaches to meet new demands, and hospital designers must also develop new approaches to respond to these demands.

Changes in clinical practices, brought about by shortages of money and skilled staff, demand enhanced efficiencies in the processing of patients. The process is greatly helped and made safer if key departments are co-located. Small footprints prevent appropriate adjacencies and therefore impose penalties in terms of clinical safety, staff efficiencies and transportation costs. An efficient hospital for the future will require floors with large footprints – say 6,000 to 8,000 square metres per floor, depending on the size of the facility. One sensible design response to facilitate modern health care delivery is to have a fat, squat building rather than a thin, tall one. “Fat” footprints will need clever spatial resolutions for the introduction of natural light and cognitive wayfinding devices.

“Smarter” patient processing has been made possible, to a large degree, by the advent and rapid development of information technology and management. Responses by architects and engineers to its implementation are at present limited to the provision of communication cupboards and fibre-optic cabling. This is largely because users themselves have not fully come to terms with the comprehensive use of new technology.

The impact of communication and electronic technology, when fully unleashed, will be a significant driver of the physical design of hospitals. In the recent past, comparisons have been made to other buildings that process people, such as airports. Though some analogies can be drawn in terms of movement patterns and the dispensation of information, clearly health facilities need their own model, tailored to their own special requirements – the need for patient privacy being just one example.

Advances in technology and new drugs are generating radically different ways of diagnosing and treating diseases, leading to the treatment of patients in non-hospital settings located within primary care centres or even at home. The hospital is therefore left with the responsibility of delivering highly acute clinical services to the very sick, catering to patients and relatives at their most vulnerable. At the same time it has to house intimidating technology and equipment, operated by a staff that is under considerable stress due to the very nature of its work. The parameters for an appropriate environment for each of these hospital users are contradictory. It is not hard to see why hospitals are the most complex of all building types to design – the design has to respond adequately to disparate criteria.

In the zeal for providing appropriate amenities for patients, it is often forgotten that the facility is also a workplace. The need to provide “break out” spaces for stressed, overworked staff seems obvious, but it is a fact that, even if such spaces are included in early briefs, that are often deleted during the inevitable cost cutting sessions that follow.

The new hospital must be a workplace for the new clinical culture – a dedepartmentalised workplace, devoid of traditional hierarchical real estate symbolism.

Cellular offices arranged in rabbit-warren-type configurations do not encourage the interaction necessary for the blurring of department boundaries so necessary for the dispensing of modern healthcare.

Courtyards/landscaped areas and other spaces for both formal and informal interaction between staff, patients, relatives and visitors must also be included in initial briefs as therapeutic areas and their integrity must be defended through the design process. The unfortunate tendency for such spaces to be “managed out” during costcutting sessions can be rectified if they are included in preliminary design briefs on which the project budget is based.

Perhaps the ambivalence in dealing appropriately with the design of hospitals lies in the inability of society to deal with the sick – do we include them in the normal patterns of life, or to segregate them at the periphery? Particular attitudes influence not only the internal layout and appearance of hospitals, but also their relationship to the city. Until the nineteenth century hospitals were pavilion-type structures quarantined away from city centres, as their primary purpose was to alleviate the sufferings of infectious patients. The early twentieth century saw the advent of clinical advancements such as radiology and anaesthesia, which allowed the emphasis to shift from “looking after the sick” to “treating the sick”. The parallel inventions of lifts and mechanical airconditioning in the building industry allowed the vertical stacking of patient accommodation atop podiums. Having steered away from the earlier image of a building housing infectious people, hospitals were now brought closer to habitation and recognised as key civic buildings with an important role in society.

Recent changes in the delivery of health services, with the emphasis placed squarely on community health, preventive medicine and ambulatory care, have made the hospital’s relationship with the city less isolationist and more enmeshed with the urban fabric. An opportunity exists to once again recast the role of health buildings within the built fabric of the community, bestowing on them an appropriate level of social significance and the civic importance that is their due. Perhaps then a greater value will also be placed on their architectural merit. The architecture of the hospital must not get subsumed by technical and bureaucratic demands; architects have a responsibility to show that a balance can be struck between the clinical demands of healthcare and a humane architecture.

Society deserves no less.

Sarita Chand is a principal of Bligh Voller Nield