Japan: 4; Ireland: 5; Australia: 1; Thailand: 3; Poland: 2; Brazil: 2; Taiwan: 3; China: 4.

That’s the composition of my current student group at Shibaura Institute of Technology in Tokyo, where I teach in English – the language that is becoming the university’s “de facto” language of communication. This transition has resulted in some interesting curiosities, such as the elective lectures on the 1960s Japanese Metabolist architects, delivered by a Japanese Harvard graduate to a class of ten Japanese students in English. But “Internationalization” – a concept that was, for many years in Japan, nothing more than a slogan – is now increasingly the focus of university ambitions. Most of the major Japanese universities now have, or are in the process of creating, English-language-based architecture programs. At Tokyo’s University of the Arts, where I taught from 2009 to 2019, we had only fifteen Japanese students in each year, plus between six and eight foreign exchange students. This high percentage of “visitors” created an interesting school culture and an exciting sense of the school’s future direction. The same was true of the international workshops that we held annually with visiting teachers and students from the AA School, the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, the University of Queensland, Bond University and the University of Sydney. Architecture schools, everywhere, can be self-obsessed and a little claustrophobic, but I think these “mixes” have opened eyes, minds and doors.

For Japan’s universities it has been relatively easy to establish the “international standing” that attracts interesting exchange students from overseas. Internationally known designers such as Kengo Kuma, Kazuyo Sejima, Ryue Nishizawa and Manabu Chiba have been appointed as tenured professors – something that is impossible in Australia, where a PhD is the necessary “key to the quadrangle” – and the allure of Japan’s aestheticism and exoticism does the rest. But inside the universities, I think exchange students are sometimes seen as time-consuming inconveniences … who don’t pay fees! And, certainly, exchange programs don’t work if the universities don’t commit enough energy (and money) to their organization and supervision. But we need to see exchange students as “message-bringers,” as people whose experiences of life and whose previous studies can contribute different perspectives to our homegrown debates. And as professional Australian architects continue their own internationalization, working worldwide and deservedly winning more and more international awards, the value of student exchange programs will become more evident. When I graduated, in 1975, exchange programs were – I think – barely existent. The complex bureaucratic agreements that the international institutes have forged have given current students a flexibility that my era couldn’t imagine. Perhaps, consequently, these students will also create an architecture that we couldn’t imagine.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 20 Oct 2020

Words:

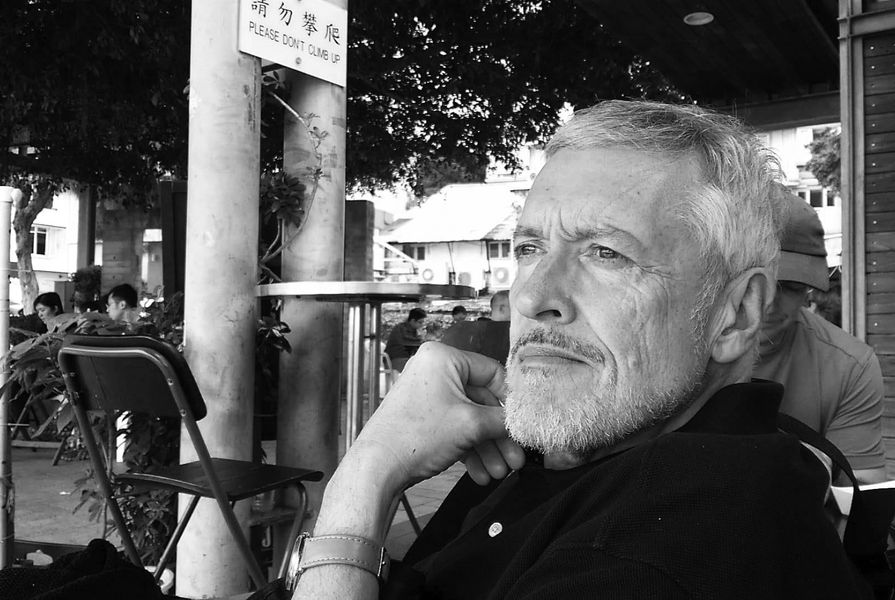

Tom Heneghan

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2020