Yarning circles have been popping up in architectural and landscape projects across the country in recent decades, with current production possibly outstripping walls sporting Indigenous-themed decal. They are a visible signal of Indigenous consultation – tick! But despite their prevalence and contemporary role as a default symbol of Indigeneity, they are deeply enshrouded in myth, misinformation, misunderstanding and misapplication. You may encounter them as a project appendix, imbued with meaning from the sacred to the profane. While not wanting to cool down the yarning circle fever gripping the nation, I invite designers to integrate this feature more meaningfully and thoughtfully.

Often built at the request of Indigenous clients and stakeholders, with the aim of facilitating positive social and cultural connections within and between communities, yarning circles would seem full of positivity. So, why do they tend to lack an applied understanding of how to create appealing areas to sit and “yarn”? And why are they often so disconnected from vibrant oral practices?

The emergence of a yarning circle in a project design tends to occur simultaneously with Indigenous engagement. But, after the initial meeting and discussion, human-centred design, iterative development, empathetic accommodation, questioning and dialogue all stop, with the result that poor built examples outnumber good ones. It’s time to rethink this haphazard production.

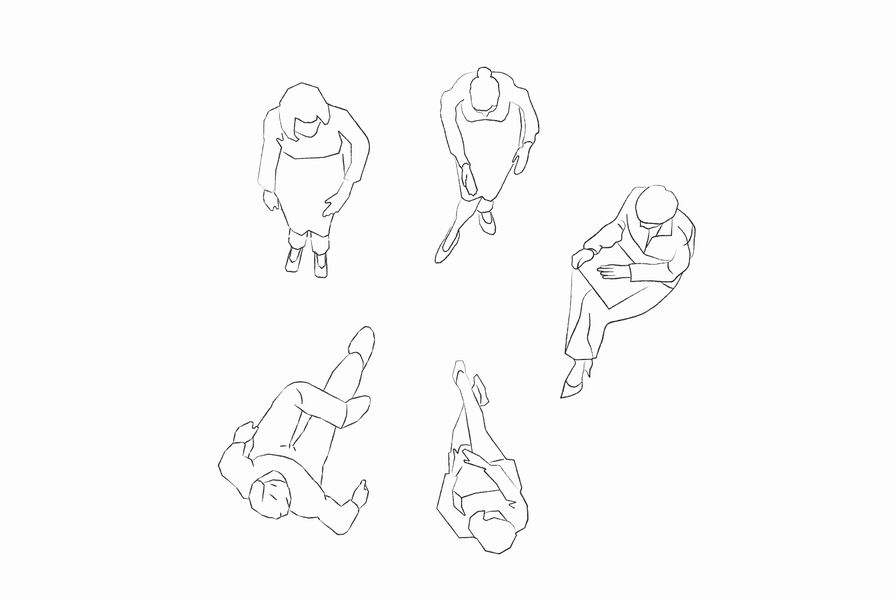

Yarning is largely devoid of any spatial affiliation or prescription.

Image: Carroll Go-Sam

Unsurprisingly, “spinning a yarn” has strong links to British English. Australian usage of “yarn” emerged from 19th-century colonial settler practices, but its everyday usage died out before the late-20th century.1 Today, yarning has been indelibly adopted into Aboriginal English to describe social oral practices that build relationality, strengthen meaning and cement affinity among Kin, Country and Community. However, it is important to understand that yarning was largely devoid of any spatial affiliation or prescription, until recently.2

In my lived experience, yarning involved small, intimate sub-sets of extended family in which stories were shared, information exchanged, and matters set straight. Sometimes, it was strictly gendered. Flexible settings accommodated yarning: in the kitchen, around the campfire or on houses’ front or back steps.

Yarning was not formally present in institutional spaces until the 21st century. The practice migrated with Indigenous bodies into diverse educational and community organizational settings. Here, yarning was used as a method to convey Indigenous standpoints through storytelling, to transform teaching and research practice.3 The method espoused equality and values of respect, dismantling western pedagogy and knowledge hierarchy.4 Contemporary Indigenous-led and intercultural scholarship continues to expand yarning in education,5 architecture, landscape, health, criminal justice and beyond.6 This seriously vibrant elaboration, with increasingly complex applications, continues to outgrow its spatial cousin.

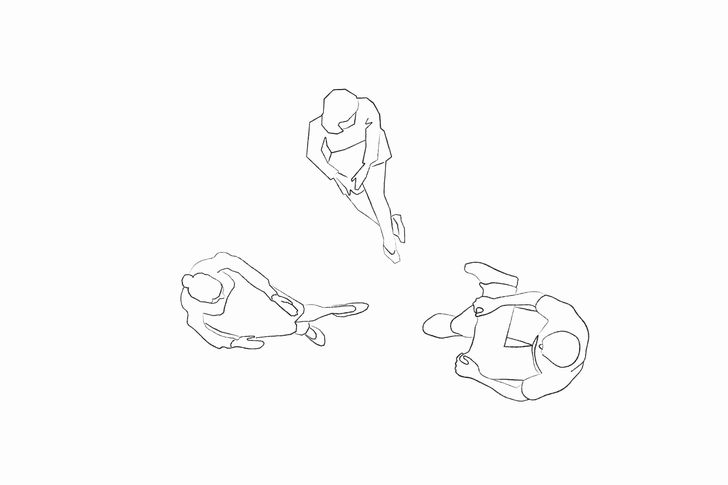

Yarning circles are a modern invention and a highly valued feature. They need to be released from rigid assumptions that shackle innovative interpretations and applications.

Image: Carroll Go-Sam

The emergence of built yarning circles paralleled the evolution of international and national Indigenist research methods. Yarning spaces disrupted western spatial power, enabling Indigenous cultural agency.7 Presently, yarning circles come in a variety of curvilinear shapes, sizes and names. Other design iterations include gathering circles/spaces/places and meeting circles/spaces/places. Despite being apparent gestures of reconciliation, many are inserted in spaces or at locations where Indigenous people are absent minorities. Some have become quasi-sacred zones of exclusion, set aside for one day a year during NAIDOC Week8. Others exist more logically in Indigenous-dominated spaces, connecting users to each other and Country.

The reductive simplicity of yarning circles has resulted in a hyper-tradition that should inspire creative applications. Hyper-traditions arise from circumstances where traditions are threatened, often emerging from histories “that did not happen.”9 Google and ChatGPT may demystify yarning circles, making them accessible. But, as with other design tropes such as firepits and bush-tucker gardens, ease of replication has reinforced myth, shutting out creative ideas for other Indigenous-inspired space types.

As spatialization of yarning demanded validation, invented traditions were added to legitimize the built form as authentically Indigenous. Some mistakenly associate yarning circles with traditional bora rings or semicircular wind breaks;10 but these spaces do not correspond in purpose, elevation, section or meaning. Windbreaks are multipurpose spaces offering protection from cold winds, while bora rings are ceremonial spaces. Likening a bora ring to a yarning circle is like suggesting that a law court, church and cemetery is a circular seat.

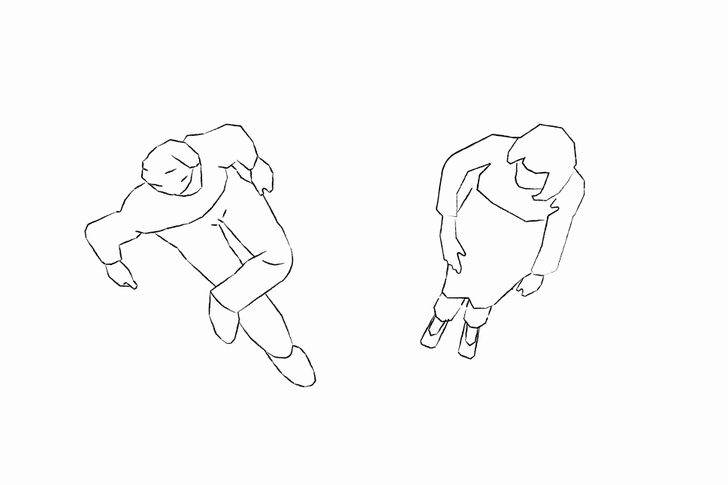

In 2001, I was engaged as an Indigenous consultant on the Musgrave Park Cultural Centre in Brisbane. A client representative on the project requested that the design team include an informal outdoor yarning space. The resulting design didn’t scream “place to yarn,” nor was it predetermined by circular geometry. Instead, it allowed users to form different seating configurations, taking advantage of long, linear stairs in the shade of the existing building canopy and a tree. The client was pleased with this simple, understated accommodation for yarning.

Similar requests occur regularly across time and place. While inclusive design practices are welcome, yarning circles need to be related to the people and places they occupy. Some are highly unsuited to their sites: dust-prone yarning circles adjacent to carparks and surrounded by flyblown rubbish bins are questionable. Awkward spatial juxtapositions make others unusable or inaccessible. Plonked at the entry of visitor centres or on the extreme edge of outdoor or indoor teaching and learning spaces, many lack sun protection. Some are so large that an audio setup for a small rock concert is required just to hear across the void. Others are functionally disconnected, appearing along meandering circulation paths, removed from nearby trees and landscaped spaces. Too many are unimaginative circular arrangements of rectangular or uneven granite blocks. The ongoing recurrence of these designs speaks to fraught cross-cultural tensions and tight consultation timeframes.

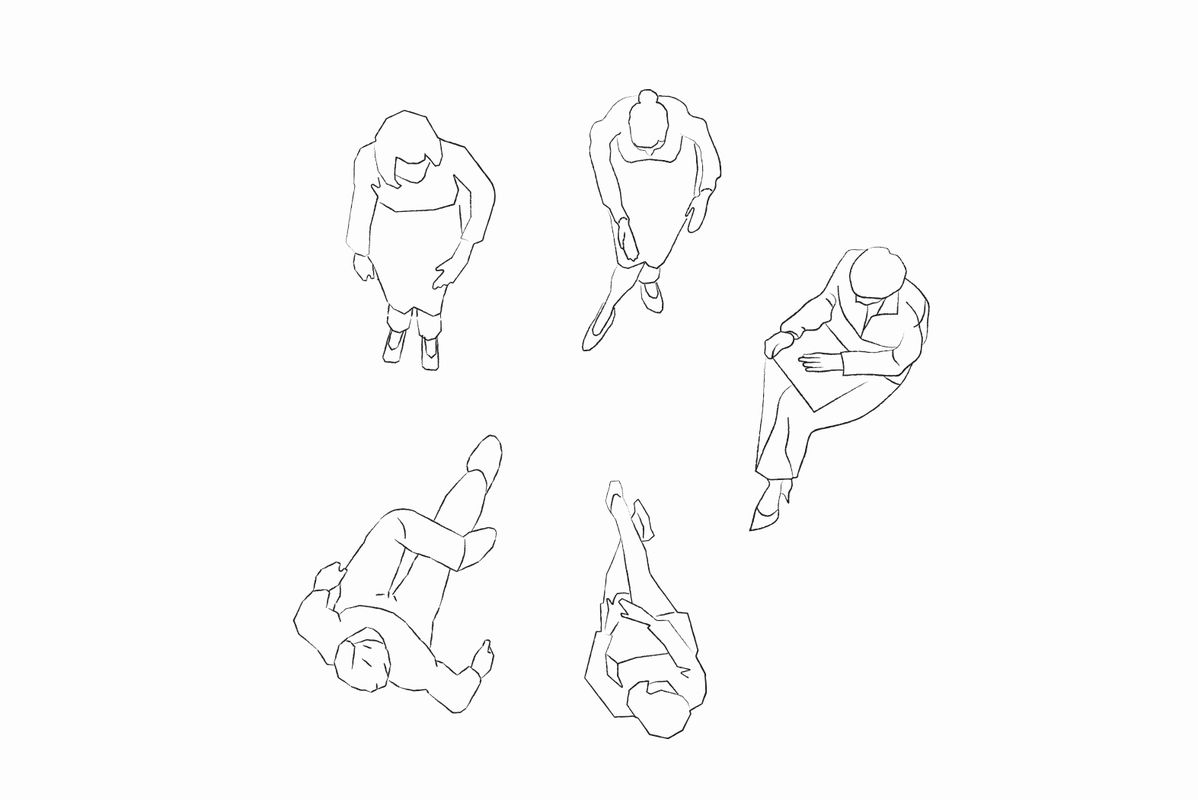

Yarning circles are a modern invention and a highly valued feature – and for these reasons, they need to be released from rigid assumptions that shackle innovative interpretations and applications. What can be done to make their inclusion meaningful? Here are my top five recommendations for anyone designing a yarning circle:

- Remember that a request for a yarning circle is not a complete brief. Instead, it’s the beginning of several conversations that should lead to an iterative design process about the feature’s purpose, users, location and form.

- Ask whether the yarning circle will facilitate Indigenous or intercultural communities of practice. (Segregated spaces in multi-ethnic spaces and no-go zones need to be reconsidered.)

- Don’t ask what is wanted, but which communities of practice persist. This will ensure that the feature taps into a living culture and is fully integrated with associated spaces and settings.

- If the yarning circle is externally located, maximize relief from weather extremes. If it is internally situated, ensure that it is an easily accessible asset for diverse communities who are informed about how and why the feature exists.

- If a yarning circle is suggested on the fly, ask whether there might be other impactful ways to imaginatively Indigenize the space.

Let’s replace the “ask no questions and build” approach with active design inclusivity. The oral practice of yarning is about shared relationality. By making this the essential design goal of yarning spaces, we will unleash new ideas that radically reimagine gathering in different-shaped spaces and forms.

- G. A. Wilkes, Stunned Mullets and Two-pot Screamers: A Dictionary of Australian Colloquialisms , 5 th ed. (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- “Yarning circle,” School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University, slll.cass.anu.edu.au/centres/andc/yarning-circle (accessed 8 September 2023).

- In 2008, Dawn Bessarab and Bridget Ng’andu identified 418,000 references to yarning in “Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research,” International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies , vol. 3, no. 1, 2010, 37–50. On 22 August 2023, I googled “yarning” and received 20 pages of variable relevant occurrences.

- L. Rigney, “A first perspective of Indigenous Australian participation in science: Framing Indigenous research towards Indigenous Australian intellectual sovereignty,” Kaurna Higher Education Journal , vol. 7, 2001, 1–13.

- M. Shay, “Extending the yarning yarn: Collaborative Yarning Methodology for ethical Indigenist education research,” The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education , vol. 50, 62–70; doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.25.

- B. Poirier, J. Hedges and L. Jamieson, “Walking together: Relational Yarning as a mechanism to ensure meaningful and ethical Indigenous oral health research in Australia,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health , vol. 46, no. 3, June 2022, 354–60; doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13234.

- L. Finlay, Building Change: Architecture, Politics and Cultural Agency (Oxford: Routledge, 2005).

- National Aborigines’ and Islanders’ Day Observance Committee.

- N. Alsayyad, “Editor’s note,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlement Review , vol. 18, no. 1, Hypertraditions: Tenth International Conference 15–18 December 2006, Bangkok, Thailand, 10–11; jstor.org/stable/23565914.

- P. Memmott, Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: Aboriginal Architecture of Australia (Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2022).