Stuff We Did – Ian McDougall

Toward the end of the 1970s, Stephen Ashton lived in the Perseverance Hotel in Fitzroy, Melbourne. We would meet in the front bar to roughhouse the recent architectural work the gang of us were involved in. To me, having grown up in a Housing Trust house on the outer edge of a town in South Australia, this was some cool urban situation. It was April 1979 and the Perseverance was everything that Melbourne was. The front bar was gloomy and decrepit with the faded glory of days when we were the national capital. Regulars, old lags who combined detailed knowledge of football tactics with astute lefty rants on what the government should do, livened up the not-much-happened-here ambience. In the autumn afternoon, the sun beamed through the stained glass onto the screen, making it difficult to see the slides we were showing, but this didn’t stop the enthusiasm. Our gang – which as well as Steve included Howard Raggatt and me – grew into the Halftime Club, a group of graduates who, angry and ambitious, curious and competitive, established a culture of architectural adventurism for a generation in our city.

Arts West at The University of Melbourne was a joint project by ARM Architecture and Architectus (2016).

Image: Warwick Baker

I had come to Melbourne from Adelaide with my friend Richard Munday in 1976, leaving an unfinished architecture degree at the University of Adelaide after a run-in with the professor. It was the time of the Vietnam War, moratoriums and student and social activism. Architecture was taught as a process, a service, based on technology and social science. Richard and I left to go to RMIT University, attracted by Graeme Gunn’s course and by Peter Corrigan’s presence, having read his article in Architecture Australia on the Venturis. RMIT was a festival of excitement and experiment about what architecture might be, about ideas and artistic action, so different from the stale air we knew.

As graduates, Steve, Howard and I were heavily involved in this ruckus because we worked for the agitators: Max May, Daryl Jackson and Evan Walker, Norman Day and Peter Corrigan. We became friends and eventually, after a decade of trying to work on our own, teaching together and instituting together, formed the practice ARM.

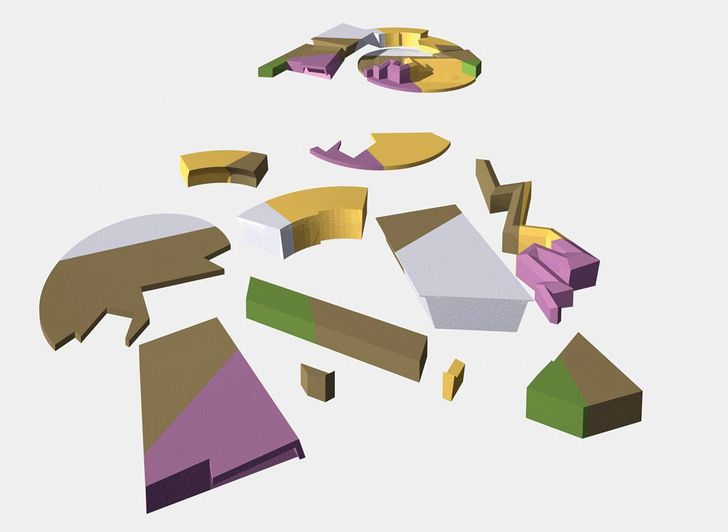

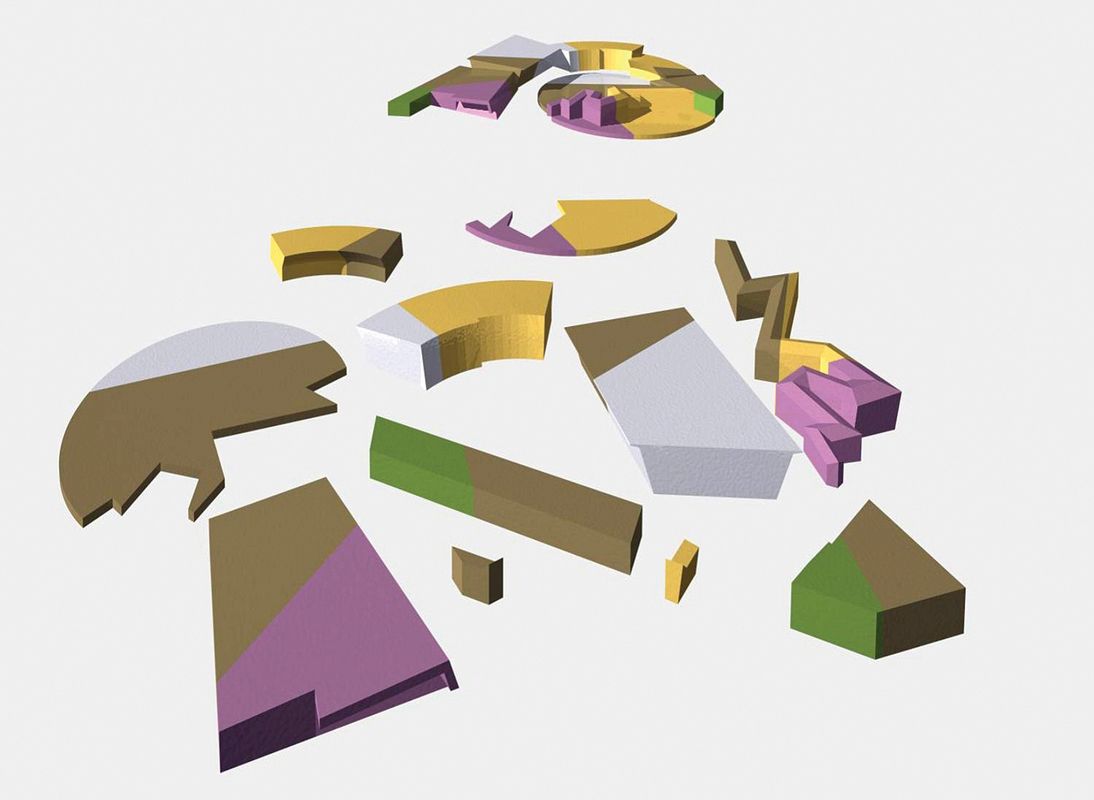

An exploration of form for the pavilions at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra (2001).

Image: ARM Architecture

Looking back, I think there were distinct things we did that established a studio that could be inventive, instrumental and propagandist at the same time. We wanted something different, something that engaged with Australia’s complex settlement, its cities, its intellectual dilemmas and its cultural contradictions. We wanted to make architecture that confronted our own lives.

Educating, writing and publishing

ARM was founded on the idea of the teacher/practitioner. A fundamental aspect of architecture is the ongoing relationship between the practitioner and the academy. To teach is to engage students in the history of architecture and in an exploration of the new. Clearly, there is no architecture without practice but there is no meaningful practice without the academy. We taught from 1981 to the early 1990s. The 80s was a remarkable period at RMIT. We taught at the night school on Wednesday nights – Corrigan, Day, Sue Dance, Peter Elliott, Ivan Rijavec and Peter Crone – ending with carafes of red at Pizza al Metro, the gang erupting in riotous dispute or tearful laughter.

But education is more than teaching. Richard Munday and I set up Transition magazine in Melbourne in 1979 as a way of exploring architectural thought, making it possible, indeed demanding, that architects talk about what they do. Transition and Halftime were twin offspring of a dissatisfaction with a mindless and cringing architectural culture in Australia. Halftime became the fight club that trained architects to think about their work, to argue for its legitimacy, to critique the ideas of colleagues and to be critiqued in turn. Through this and through writing about architecture, we tried to develop a language to discuss what we were doing. We were active participants in many magazines: Transition, RMIT Major Project Review, Pataphysics, Backlogue: Journal of the Halftime Club and Subaud . I attempted to bring this mission to the mainstream journals of Architect Victoria and Architecture Australia.

Publishing, especially independent publishing, is crucial to the development of a vibrant architectural culture. Give each generation publishing technology and independence and you have an energized architectural culture.

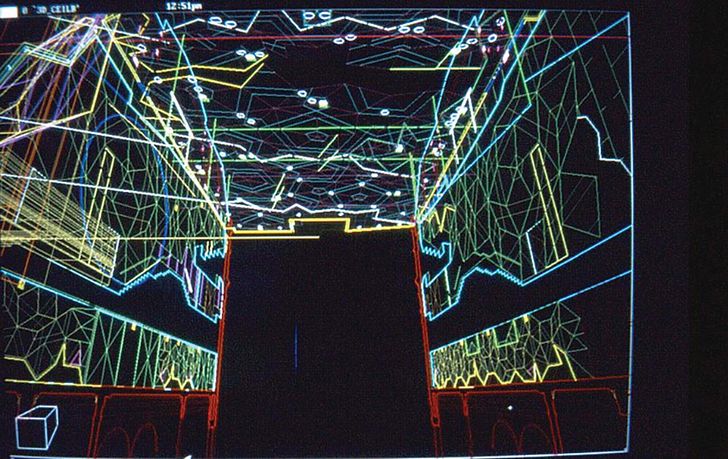

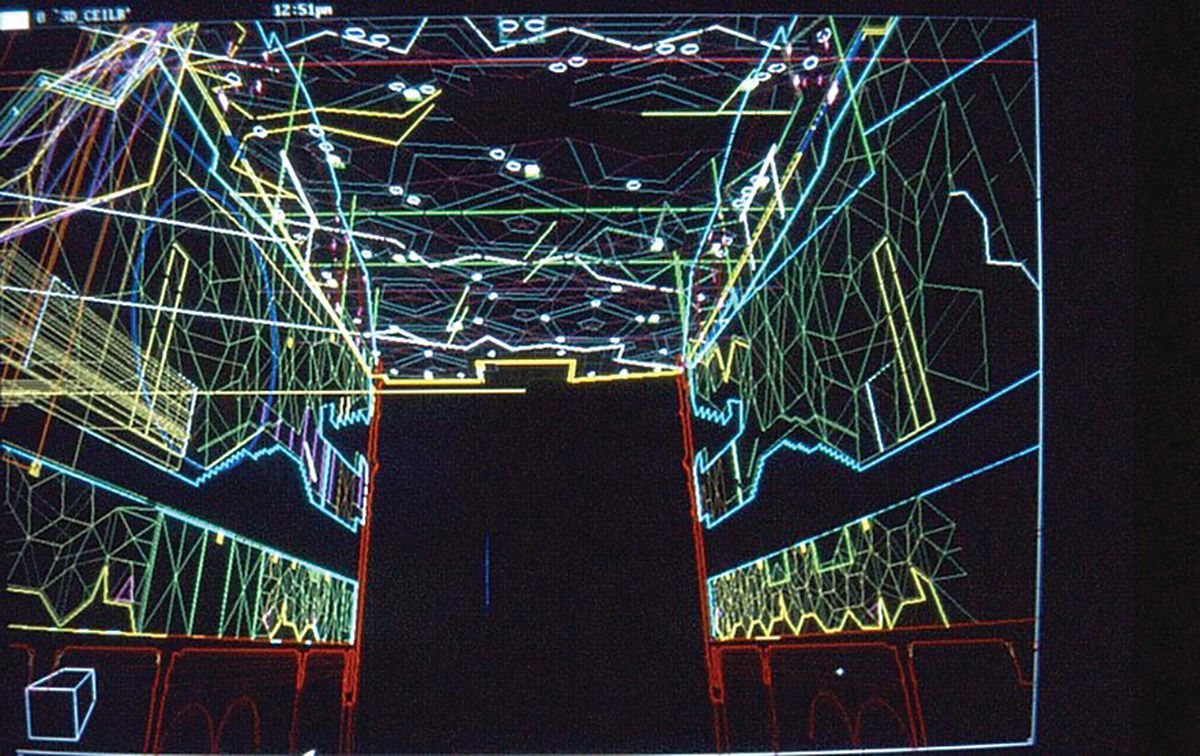

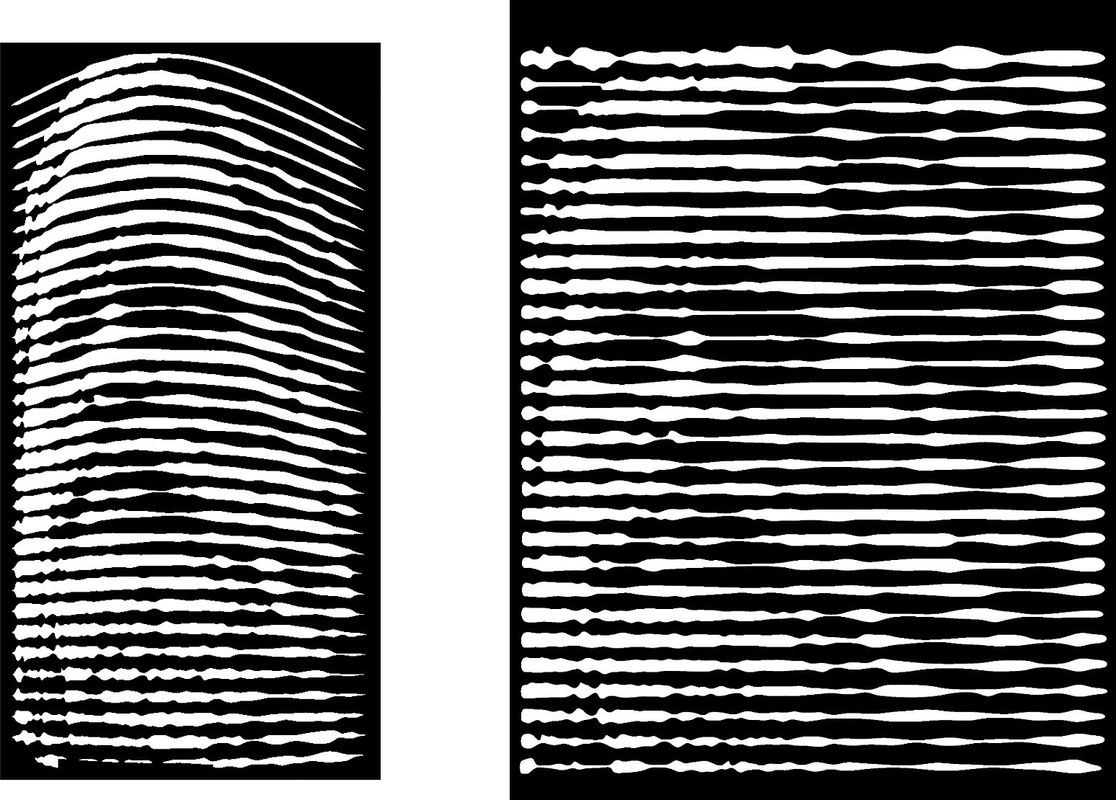

With the uptake of computers from the mid-1980s, CAD software such as AutoCAD, 3ds Max and Rhino became integral to the design processes of ARM Architecture.

We went digital

We architecture students of the 1970s were fed a dream of a computerized future. In your future office, we were told, there would be large bureaus coordinating standardized drawings of standardized components, assembled in factories and shipped to site. As students, we excitedly worked on mainframes with punch cards, drawing window details. The progressive firms in the 80s used VAX networks and specialized workstations. But in 1985, we chose a cheaper path. We purchased some pale beige IBM clones, with AutoCAD release 2.1 and pre-written tablet menus, and glimpsed a whole new way of imagining and drawing architectural space. The excitement was palpable. In 1990 we leapt into 3D modelling software: a forerunner of 3D Studio, then 3ds Max, Rhino and animation software. We were also early adopters of Photoshop, Corel and other image manipulating software. These became integral to our design process, not as drafting tools, but as makers of form and imagery.

We love building

Colleagues are often surprised that we love to build. We approach the craft of building not as managers of a process, nor as ideologues with a book of rules about structure and skin, but as dreamers who make things. We have built things a quantity surveyor cannot cost, things that are ambitious, things about which others wonder: how?

In 1996, we worked on a refit of two dreary, badly lit subterranean triangular spaces in the Victorian Arts Centre (now the Arts Centre Melbourne). Benefactors were supposed to sign large sponsorship cheques here but hadn’t recently. We connected the spaces with a backlit, forty-five-metre-long wall containing panels of glass marbles and consumer junk – cheap digital watches, plastic tiaras, a shattered parking meter – and lit with fluoro tubes. We presented the idea without knowing how to build it. Our research found marble suppliers, plastic fabricators, industrial chemists and a lighting expert. ARM became the largest importer of glass marbles in the country in 1997 and we placed the marbles in each panel ourselves.

Our approach to building is not the structuralist doctrine of skeletal matrix and infill screen. Our roots may lie in Gottfried Semper’s proposition of “material dressing” and his basic element of “enclosure.” The significance of building is integral to the making of our projects and the final “dressing” can be independent of any relationship to the (core-form) supporting matrix. In other words, spaces are thematically “dressed” independent of the rationalism of the shell, as in Arts West at the University of Melbourne. Our approach is not about the systemized assembling of components, but the composing of spaces with surfaces that are “made.” We use the skills and knowledge of the trades to make the building, collapsing the contracting process so designer works with maker.

An architecture of ideas

We have always believed in an architecture of ideas. We have argued long for architecture as an intellectual activity, an exploration of the relationship between rituals of life and buildings. Our aim was never the state of the simple and wonderfully plain. Ours has always been an architecture driven to find something, constructing narratives that might resonate beyond a building’s program or physicality, or exploring formal manifestations of ideas embedded within our culture. Our work regularly returns to architectural ideas of human experience that are prohibited in mainstream architectural doctrine.

These explorations include the “impure,” the figurative and the local. We have embraced the impure – the not-beautiful, the abject, the transgressive, the contradictory. We have explored the nature of the figurative in giant books or faces on buildings, in the decorative as an architectural tradition and an artistic and political statement. And we have attempted to understand localism, a non-insular and deliberate provincialism founded partly t o ring-fence a safe zone to work in, holding back the onslaught of the international carpetbaggers from the centre. We wanted to find its language, its provincial history, and to counterpoint that with the international context.

Architects of the city

Architecture is a civic act. Unfortunately, the city is a place of toughness and negotiation. Our stance means that the individual house is a distraction from the focus of the public and the commercial project. It also requires advocating for architecture in the institutions of the city: government, lobby groups and professional bodies. We have been active supporters of the re-establishment of government architects and of the Australian Institute of Architects being active in government policy. We also consciously sought the compromised ground of large urban projects: the shopping centre, the sports arena, the renewal of large urban precincts and the mass residential apartment building. These are commercially driven and politically complicated, in a way that connects directly to the Australian urban economy. It is important that designers work in these realms, because if our leading designers do not participate, they deprive our cities of some of our best thinkers in architecture. And why? Is it vanity?

In April 2016, Steve was propped up on the couch, recovering from his chemo, directing Howard, Tony Allen and me to enter his wine cellar under the house and get a bottle of whatever but not the Grange for our weekly catch-up. We tried not to do too many jokes but he inevitably starts Sir Desmond Glazebrook (“the city’s a funny place, you know, Prime Minister”) and makes us all laugh. For over thirty-five years, with angry intent tempered by a sense of the absurd, we tried to build a foundation of patronage for ideas, encouraging a language for discussing an intelligent architecture, supporting a college of design here in our city. And also to complete some quite interesting projects. Perhaps there was a little success.

An Architecture of Ideas – Howard Raggatt

It has been something of a tradition of the A. S. Hook Address that it is an opportunity to reflect broadly on matters of architecture and the profession rather than addressing concerns about what architecture itself can be or become. While we like to think we share these concerns, we also hope to present something closer to the bone of our own efforts to practise. From time to time our work has been described as “an architecture of ideas” and yet we have always wondered whether such a thing is really possible. We hope to discuss this theme and to use our work to illustrate the possibility of such an architecture.

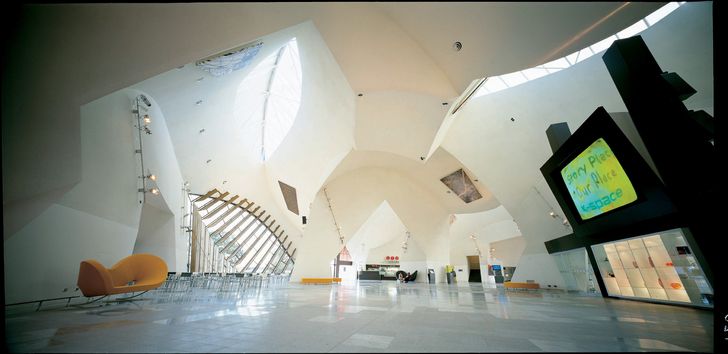

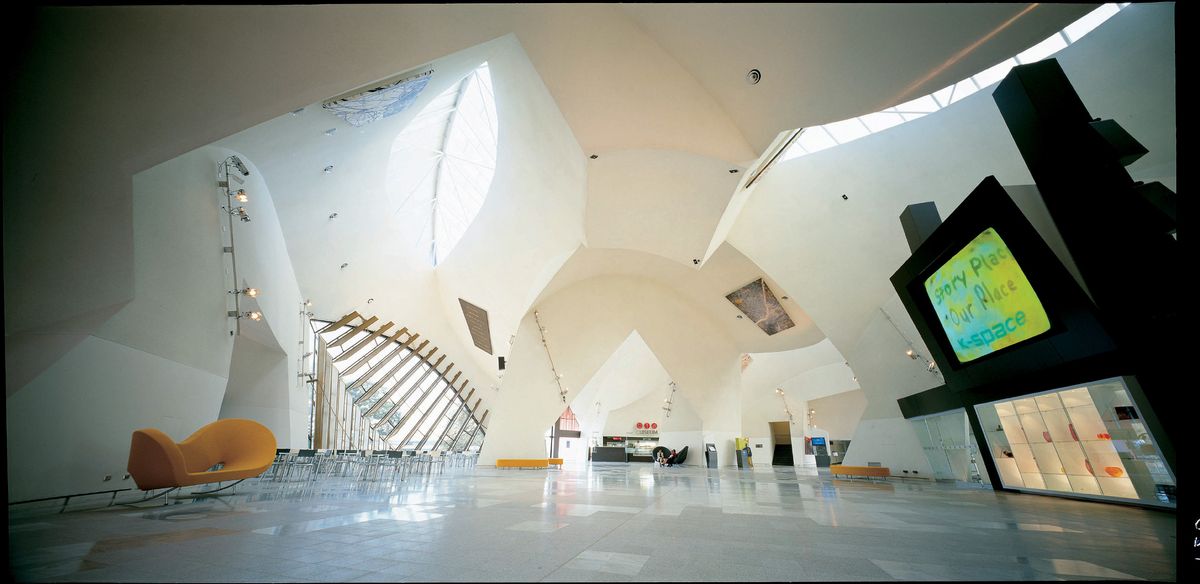

The Great Hall at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra (2001). Photography: John Gollings

Image: John Gollings

Questioning

To this end I would like to begin with the overarching condition of a genuine questioning along the lines of what Jacques Derrida seemed to allude to in his conversation with Richard Kearney (1981) when he said, “I think that all genuine questioning is summoned by a certain type of eschatology …”

Of course, architecture is necessarily expected to be an “answering,” a solution to real problems, so we wonder if it’s possible for it to be a “questioning” as well. And is it possible for architecture to somehow be the physical form of that questioning, to retain and project that sense of questioning in real time? And if it is a genuine questioning, is such an architecture also summoned by a certain type of eschatology, as Derrida insists? Is it required to appear somehow and, if so, how would it look? What would it have to say?

In our National Museum of Australia (NMA), we explored what possible forms could sustain such a genuine questioning. We realized that the building, as a social history museum, could only ever be a fragment of a much bigger picture, and so we arranged it as a series of adjacent pavilions as if fragments of that picture, or as if phrases of that much longer story.

Each pavilion we treated as if somehow found or pre-existent (“summoned,” if you like, in Derrida’s terminology). Each pavilion is intensely particular, intensely exacting and intensely juxtaposed with the others, as if contesting its rightful place in that bigger picture, as if questioning even its own authenticity, wondering if it somehow resists self-satisfaction. Does it have apprehension and faith in equal measure? Does it still ask, “What do you reckon?”

Now I would like to discuss our work under four thematic categories: exegesis, visible and invisible, buildings you can’t draw, and puzzling.

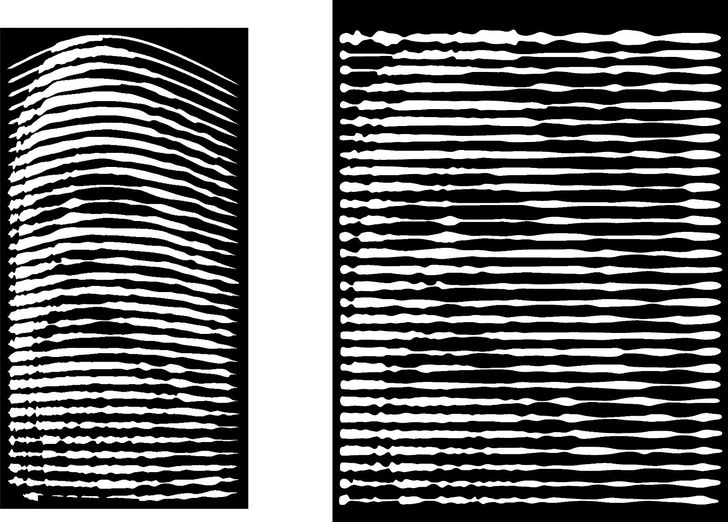

For Perth Arena, ARM Architecture selected eight pieces of Lord Monckton’s Eternity Puzzle to compose the building’s perimeter and facades.

Image: John Gollings

Exegesis

Can architecture really be an exegesis? Can it not only sustain critique, analysis, context, history and interpretation as discourse, but also be an exegetical object, itself an object of interrogation, itself a visible interpretation?

Many of our projects aim to explore another condition of the exegetical, from the literalism of the St Kilda Library extension, the ornamental strategies of the NMA, the physical operations of the Howard Kronborg Medical Clinic to the city-wide gatherings of Storey Hall as resurrection city. But for now, one example should suffice.

The Howard Kronborg Medical Clinic began with the famous photo of Robert Venturi’s mother’s house, with his mother sitting in the front porch with her book and flowerpot. We photocopied it by hand, slipping the original image across the glass as if in search of its unspoken allegiance, its unsuspecting references or its subconscious denials. This uncanny copy we scanned and pixelated and carefully documented, ready for construction.

Is this an exegetical object, then? This radical interrogation, this construction of shadows, wobbles, stretches, this pixelated detail, this stutter, this faithful misinterpretation, including even Robert’s mother, with this change of use, this strange translation, as if denial of expression now, and another accent altogether?

Visible and invisible

My second theme explores the possibilities for an architecture of the invisible. We wonder if it’s possible to make an architecture that defines what it is not rather than what it is, as if a trace rather than merely expressions or aspirations, somehow about what is hidden rather than the thing itself, an object of waiting and longing instead of gratification or fulfilment.

Here we examined three different conditions of the invisible: the cast at the Great Hall of the NMA, the subtractive Boolean string also at the NMA and the protective “polystyrene” forms at the Melbourne Recital Centre.

While the cast and the subtractive Boolean make an exacting fit with the invisible, we realized that polystyrene packaging makes this fit ambiguous, even mysterious, the precious protected object now intangible, even evocative. Now the invisible is as if no longer determinate, its space no longer constructed purely in the negative, its volume, structure and weight, its typological forms now strangely incongruent, its memory of the precious as if now lost in its whiteness, its sense of longing now almost excruciating, its resonance of the invisible as if now somehow an object of surprise as well.

Buildings you can’t draw

This tests the very means and conceptualization of our architectural methodology to question the boundaries of our imagination. Once upon a time we could draw buildings in plan, section and elevation. We could imagine them in three dimensions and build them from the ground up. But now we no longer want to draw buildings we already know – we want to go beyond what we can already draw, beyond what we can already imagine.

The concept of buildings you can’t draw has become for us a kind of epistemological enquiry aimed, if possible, at the means of our conceptualization. Here drawing stands for our powers of preconception, for our experience, our dexterity, our hand-eye coordination, our 10,000 hours of practice.

We explored this abandonment of drawing in a series of ongoing projects, including the Green Brain at RMIT University, the competition for Grocon’s tower building on the Carlton and United Breweries site, and the Elizabeth Quay waterfront masterplan and public realm in Perth. Instead of drawing, we began the Elizabeth Quay masterplan with an animation. It begins with a single source, that first splash as if a Wagyl egg, as if a re-enactment of that Dreamtime, as if animation could somehow wind us all back to there, or otherwise transport us beyond our imagining.

Instead of drawing we can only watch in breathless abandonment as these exquisite interference patterns emerge as if by magic. Frame by frame we examine them, as if it were possible to unravel them, every one a feast of vivid imagining, transcending what we once called genius, till gradually we learned to tame them or should we really say corral them. Now, instead of mastering, we find ourselves swept along as if by natural forces, enveloped in an ecstasy of interpretation.

The water’s edge configuration, the island, the planting, the paving patterns and water feature, building locations, level changes, retaining walls, seating, steps, gardens, lawns, lighting and power poles all become reflectors of that animation, infinitely responsive at any scale, as if to embrace every emergent contingency.

Instead of drawing what we already know, here animation takes us to another kind of delineation, another inspiration. One that we no longer necessarily command but instead find resonance in, find explication, as if freed from what was once imperative, once called definition, but has now become interpretation, memory and narrative.

Puzzling

In the fourth theme, puzzling, we have tried to acknowledge an architecture that remains somehow deeply problematic. Is it possible, we wonder, to configure what we might otherwise call perfect resolution, operation or workability and yet contest matters of longing and desire, matters of ultimate expectation, even that matter of eschatology that Derrida required?

Two examples are Perth Arena and the Barak Building at Swanston Square.

The Barak Building in Melbourne.

Image: John Gollings

A large and exquisitely complex project, Perth Arena had the highest expectation of urban integration and patron experience, to say nothing of management functionality and money. Pragmatically, the project became for us an avocado – a thing with a hardcore functional centre, but surrounded by a kind of soft perimeter interface.

Our inspiration was threefold: Western Australia’s first building, the twelve-sided panopticon Round House; the twelve-sided ideal cities of the Renaissance; and the impossible twelve-sided Eternity Puzzle by the crazy Lord Monckton, with more permutations than subatomic particles in the universe! From this Eternity Puzzle of 209 pieces, we selected eight from which to compose the building’s perimeter and facades. This was no easy marriage, these fragments of eternity. No matter how hard we tried, they remained indeterminate, insoluble, even irrational.

No matter how cleverly juxtaposed, how mysteriously emblazoned, how boldly urbanist, how secretly transfigured the pieces were; no matter how gritty our contextualism was, how difficult our junctions or how elegant our surfaces; no matter how interconnected the spaces were, how spectacular their volumes or how many beautiful acoustic plywood panels, projected shadows or supergraphics they had, the building remains puzzling, as if in a language no longer spoken.

After everything that discipline, research and innovation could uncover or teach us or achieve, we hope that what remains, what puzzles most, is daring us to subjectivity again, daring us to find nirvana waiting.

The Barak Building gives a very different perspective on the puzzling. Instead of the sharp definition of discrete pieces, it explores instead an optical illusion of something more emergent.

The Barak Building facades facing the city feature an image of William Barak, a Wurundjeri Elder, political activist and artist, translated into the continuous balustrades.

Image: ARM Architecture

Our site was once home to the historic Carlton and United Breweries at the top of Melbourne’s civic axis that extends down Swanston Street and St Kilda Road to the monumental Shrine of Remembrance. For many, the Shrine represents the bloody sacrifice of the new nation of Australia. Yet this new nation remains a fraction of the story of our land, so with our building we hoped to make a corresponding sign of that deep history of the land, past and present. Our idea was to mark this deep history with the visage of William Barak, Wurundjeri Elder, political activist and artist.

Our technique was to translate an image of Barak into the continuous balustrade elements of our highrise apartment tower. Up close, perhaps these computer-generated elements become just a stylish figuration of the view, but from a distance, and from so many places around the city, quite unexpectedly, they become the face of Barak, now looking out over the city and his land, springing forward as if from that deep history.

Our book Mongrel Rapture: The Architecture of Ashton Raggatt McDougall has a page titled “Not Fucking Blue Enough” (page 430). This is an apocryphal quote from Steve Jobs, who was, they say, seen screaming into his mobile phone just before the release of the iMac G3 in 1998.

I am often reminded too of David Batchelor’s term “chromophobia”: “A fear of corruption or contamination through colour that has lurked within Western culture since ancient times … apparent in the many attempts to purge colour from art, literature and architecture, either by making it a property of some foreign body, the oriental, the feminine, the infantile, the vulgar or the pathological – or by relegating it to the realm of the superficial, the inessential or the cosmetic.”

In Mongrel Rapture , we say “We hate colour too!” and that in the end we use it only because we feel we must, or we feel somehow that it’s called for, or as if we are summoned to comply. As Steve Jobs suggests, perhaps colour is something we can never quite get right, but it is indeed strangely fundamental to an architecture of genuine questioning, to what Derrida calls summoned, and to that eschatology of the impossible surprise.

Ian McDougall and Howard Raggatt are founding directors of ARM Architecture with Stephen Ashton and together they are recipients of the 2016 Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 28 Jun 2017

Words:

Ian McDougall,

Howard Raggatt

Images:

ARM Architecture,

Courtesy of ARM Architecture.,

John Gollings,

Warwick Baker

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2017