The National Museum of Australia (NMA) is garrulous, colourful and melodramatic, while being one of the few occasions of serious civic discourse in the medium of building in this country. The buildings which make up the museum mix populism with architectural erudition, and yet somehow remains unfamiliar, surprising and often humorous. While appearing to be assembled from a salvage yard of cultural allusions, architectural motifs and visual puns, as buildings they remain unprecedented, conscious architectural inventions of the highest order. Those who think of architecture as a kind of elegant ordering of conditions and requirements will find the NMA willfully perverse, because the fact that it is a simple, efficient and well considered building is largely invisible under a delirious elaboration of the building’s own conceptual system. In this uninterest in mundane tasks, and in its contrived spatial effects and conceptual elaboration, the NMA is quite like Baroque architecture. I don’t mean this comparison in a stylistic sense, what interests me at the NMA is a certain Baroqueness in the comportment of the architect in relation to the work. This is especially apparent in the status given to geometry and a pessimistic but unceasing attempt to make meaning.

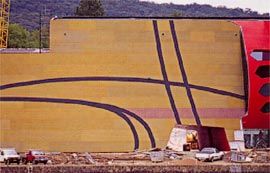

In formal terms, the NMA is loud and unstable. There are numerous buildings and expressed parts. There is a very wide palette of materials (including some remarkably beautiful precast concrete) and a strong use of colour and applied graphics. There is also an optical illusion where built shadows are applied to the walls to double the effect of real shadows. Overall, there is a sense of movement – as if the buildings were shimmering in and out of focus, growing and shrinking, changing and not changing with the passage of the day. In this way, the NMA is sensually pleasing. However, the architecture is also intended to problematise one’s sense of form. The buildings are formed from quite blunt, lumpish volumes, which are then cut and deformed according to an abstract procedure.

The results are sometimes beautiful and sometimes not, thus premiating the process over the result. This also suggests movement, not at a perceptual but at a conceptual level. One imagines a prior state, a disrupting action, and a possible ongoing process by which the buildings might have other permutations. The pretence here (one that has been perhaps overly popular among architects in the late twentieth century) is that form arrives automatically and is thus arbitrary. This is, to my mind, a false modesty on the part of the architects, a kind of theatrical conceit. But then all that I have mentioned of the museum’s dramatic twists and illusions of movement would be mere theatre, if they were not understood as the outward signs of an occluded geometrical schema and a coded but dangerously frank discourse on the national identity.

The architectural approach is close to the ideology of the museum. The NMA attempts to present Australia as an unfinished project and an unresolved concept – a nation in which an appropriate level of faith and affection balance a paucity of agreed beliefs and doctrine. One of the new genre of “social and cultural history” museums, the NMA is itself a problematic and uncertain enterprise. Preserving and displaying artefactssuch as the ABC’s first outside broadcast van or Azaria Chamberlain’s matinee jacket has little to do with the previous logic of museums. No scholars will study these objects to develop knowledge of Australia’s past. They are housed so lavishly on Acton Peninsula for the purpose of affecting the visitor with those mixed feelings of belonging and estrangement that make up the national sentiment. At the NMA, themes and classifications no longer serve to order materials and make them accessible; rather artefacts are loaded in to the space to produce the thematic experience which is the point of the place.

If the NMA is experienced as a concoction of affects and concepts, this nevertheless sits within a simple and efficient parti, which is well scaled to the landscape. By distributing the building volume around the shores of the peninsula and creating a captured garden space, the architects have given the museum, which is relatively small, a sufficient exterior scale to have a presence when seen across Lake Burley Griffin. The central Garden of Australian Dreams is also vital to the iconography of the museum. (I saw it incomplete, but it seemed to lack the spatial punch to match its frantic iconography.) The strategy also has the advantage that the building is quite shallow in plan with opportunities for access and connecting views between the lake and garden. In plan terms the museum is very intelligible with strong spatial sequences, punctuated thresholds between the various sections, and memorable orienting views. The building is modestly low: framed and sheltered by existing mature trees, it seems to grow out of the landform of the peninsula with only a large steel tower, intended to be the icon and landmark of the museum, rising up to contest the landform in fanciful aerial loop.

This looping steel thread is not only the emblem of the museum but a clue to a complex and nuanced geometrical schema by which the architects imagined that Burley Griffin’s famous axes, which lay out Canberra, are tangled and knotted on the site.

Instead of crossing and thus centring the building, the effect of tangling the axes is to throw the buildings outward to the edges of the peninsula as the site planning required.

But the geometrical procedure also provides a master narrative for the museum as a whole in which Australia is understood as “many stories tangled together”. This simple allegory is perfectly pitched to the museum’s ideology. The tangled axes become an enormous string, an extruded five-sided figure which is mostly invisible except as the void it makes where it intersects and cuts the main building volumes.

This way of making buildings is remarkable, firstly, because it is only possible because of relatively recent computer technology in design, surveying, and sheet cutting. More importantly, while the geometry is palpable and apparent to any observer, it is impossible to understand without diagrams, and difficult even then. But once begun, an exegesis opens not so much to a solid truth as to an infinity of interpretation. As with the Roman Baroque, this geometry is always felt but never, finally, understood. When Borromini designed S. Ivo della Sapienza, Rome, he used a six-pointed star both to generate the structural form of the segmented dome and to evoke the symbol of wisdom. However, the geometrical figure never aligns with the building elements that it has generated and thus it remains, not so much a secret, as a truth anterior to the building. The star remains behind the veil which (for a counter-reformation Catholic) properly separates life and durational experience from the absolute and timeless world of symbols. For Borromini, a five-sided figure would be the sign of Christ represented in His five wounds, and if one thinks, with the Baroque, that interpretation is infinite, then the string which makes up the NMA can be the Redeemer as well as Griffin’s axes.

One of the principal points of the action of the string is where it loops around the main galleries, stripping off their external skin and cutting a channel at ground level. In terms of building organisation and everyday experience, this is a point where internal levels change, and where the visitors can orient themselves and see and understand much of the building organisation. Symbolically, one is on the line connecting Capitol Hill to the internal Garden of Australian Dreams, on the line between Jerusalem and Eden. But to be there, in both the everyday and symbolic sense, is to be connected in a liminal perception of form. The red colour, the repeated 108 degree angles, and the big steel loop viewed in the distance are just about enough perceptual information to guess that something five-sided has sliced through the building bulk. With the allegory of the string explained, this apparently jumbled space springs sharply into focus, so that, like having found a face in the clouds, it becomes impossible not to see the form of the invisible five-sided string.

With a more elaborate explanation, perhaps a printed guide with diagrams, one could understand the whole master narrative of geometry of the site, and yet this is a very complex task and strangely unrewarding. It is not that, having understood the geometric code, the experience of the building then becomes richer. Rather the geometry acts to take one’s experience of the building and throw it into a space of symbolic identifications.

One of the aspects of the NMA that is bound to be controversial amongst architects is its use of architectural references. Elements of buildings by Le Corbusier, Walter Burley Griffin, Daniel Libeskind, Eero Saarinen, James Stirling, and Jørn Utson are more or less visible in the design. For instance, a replica of the Villa Savoye, full scale, and reasonably accurate except for its being coloured black, forms an end to one wing of the Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Many of the quotations are less explicit than this, giving the visiting architect another kind of puzzle that parallels that of the string and its geometry. Ashton Raggatt McDougall is already notorious for these kinds of appropriations in the firm’s earlier work. There is a variety of opinion that sees this approach to design as mocking the client and lay visitor, because an architecturaleducation is required to make the identifications and get the joke. However, in my experience, the public, when attending to a building as architecture, for example touring Parliament House, are perfectly happy for the building to require a guided reading. If anyone is being mocked by the architectural references it is architects who think that the meaning of buildings can be self-evident and exist without interpretation.

For instance, the most dramatic and memorable space in the NMA is the Main Hall.

This space can be read as a built commentary on the Sydney Opera House. The grand ceiling is a series of intersecting shells in a complex geometry. But architects will notice that it comes down onto columns remarkably like those of the TWA Terminal at JFK airport in New York. This building was designed by Eero Saarinen at the time he judged the Opera House competition. After returning to the USA, Saarinen redesigned the shells, and the crucial twisting columns on which they sit, with the lessons he had learnt from Utzon’s Opera House scheme. The window wall and sky lights into the NMA Main Hall are framed with steel mullions which replicate those framing the glass walls which close the Opera House on the harbour side. These glass walls, designed by Peter Hall after Utzon had quit the project, are widely admired but under threat by Opera House purists campaigning to “restore” the building to what can be deduced of Utzon’s intentions for it.

The Main Hall is thus a little lesson in architectural history, an opinion about a present architectural controversy, and an essay in the complexities of the idea of originality in form making. This much of the Main Hall does then require a specialised knowledge.

But this architectural coding is less remarkable than the geometrical and symbolic coding. The ceiling of the Main Hall is a notional cast taken from a knot made with the virtual string. This knot is an allegory for the binding together of the threads of Australian history, and its virtual nature, its actual non-existence, mean that in the Main Hall it is the throngs of visitors who make this knot as they move through the space. The sense thatthese alternative readings provoke is, as in Baroque architecture, that culture is the act of proliferating meaning in the face of disorder. If one begins, as the Baroque did, with the fact that just about anything can come close to meaning something and that the most carefully wrought cultural artifacts fail to reach true significance, then the consequence is clear. One must either admit to the meaninglessness of existence or pile up stuff deliriously, without fear of contradiction or repetition, in the hope of the miracle of meaning.

Count the readings of the Main Hall. With one’s body, on the skin as it were, this is an affecting space; it feels like the secular cathedral that the brief required. With a few visual clues and hints at the concepts involved one can mentally unravel the space in two directions – first, as the space of an enormous five-sided thread tied in a double knot and second, as a play on the history and criticism of the Sydney Opera House. Each of these rhetorical figures, the knot and the alluded Opera House, are then the basis for an allegory. The allegory of Australian history as tangled stories being formed in the purposeful knot of citizenship requires an exegesis of the kind the museum’s guides and pamphlets will undoubtedly provide. The architectural allegory has the same structure. It is an occasion for conversation, for story telling and the fact that (most) architects will not need a guide to start them going is no insult to the public. Architectural history is not the prime code in the building. The NMA exterior skin is covered in bumps which form huge messages in braille. This does not meant that the building especially privileges sighted braille readers, any more than it does architects; the ease with which one reads the braille or the architectural references is not the point. The building incites acts ofinterpretation on every occasion and the message that arrives is generally less important than the exhortation to use the building as civic culture.

While much of the braille exists for the joy and humour of puzzling out messages such as “she’ll be right” and “such is life”, rumour has it that at one point the buildings say “sorry”. This refers to the Commonwealth Government’s refusal to apologise for the past treatment of Aborigines, especially for the policies of forced adoption, which many believe to be a form of genocide. Other references to this issue include the cartoon-like use of the colour black as a symbol, an internal stair in the Gallery of the First Australians, which has the appearance of a gigantic black cross, a framed view of the parliament flag on axis with the entry hall, and a comparison of the fate of indigenous culture to that of the Jews of Berlin under the Nazis. Understanding this last reference requires knowledge of Daniel Libeskind’s recent Jewish Museum in Berlin.

There have been some charges of plagiarism on account of this reference which to my mind are spurious and nonsensical. The more serious issue here is what the figure of the Berlin Jewish Museum means at the NMA. It seems likely to me that this will be read as a straight comparison between the history of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia and the Holocaust, and that this will inflame the government but perhaps also indigenous people who may not find this a politically productive comparison, and Jewish groups committed to defending the uniqueness and singularity of the Holocaust. Libeskind’s building is not a Holocaust museum but one dedicated to the cultural achievements of Berlin’s Jews. But it remains to be seen if the comparison can be made so finely when, as I’ve pointed out, the whole building complex is based on simple identifications spiralling into proliferating associations. This allegory of the destruction of cultures and societies with its double code of architecture and civic discourse is like that of the knot of the Main Hall, but politically it is of another order and will undoubtedly cause controversy.

No one seeing the National Museum of Australia can doubt the architects’ skill and determination, but many will doubt their wisdom, taste and professional comportment.

However, if the project raises these doubts it should be understood in the most general sense of questioning what we know, or think we know, about architecture and how a knowledge of architecture relates to its practice. The problem with much of the simplistic neo-modernism now being built is that it supposes that one can know what architecture is, for sure, before a project begins. Whereas, it seems to me, the architects of the NMA, as in the Baroque, have begun with radical doubt about whether architecture is even possible, and then attempted to reaffirm the necessity of it by building with a strident exuberance. This is a project of ecstatic pessimism, and deciding if it is pleasing, good, or correct is somewhat to miss the point. While sceptical of the power of form to hold and close meaning, the architects of NMA have managed to say something about the national story and achieved what few today think possible or desirable – a “high” architecture of figurative meaning.

Dr John Macarthur is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of Queensland

Architect’s Statement

Our hope for the National Museum of Australia was the making of a place in both visible and invisible space. At first we imagined a kind of platonic triangle like an ideal knot, like a cloud, like a bodily epistemology, and then as if projected to ground, like a shadow, like a promise made visible.

We liked to think that the story of Australia is not one, but many tangled together. Not an authorised version but a puzzling confluence; not merely the resolution of difference but its wholehearted embrace. We hoped to make a place vividly local, rooted in Walter Burley Griffin’s garden city, rooted in the local country, but also we hoped to make something projective, to make a sign of our longing. Instead of any singular entity we envisaged a series of intensely adjacent structures, like puzzle pieces, as if each tested plausibility, as if each became an evocative typology, as if each belonged to another language, encouraging the idea of reading, encouraging hope in an exegesis of promise. At the centre of the museum there is a great open space called the Garden of Australian Dreams; like the field of a sporting stadium it is a new cultural arena, a palimpsest oftimes, both myth and tragedy, demarcation and dream.

This is what we can see immediately, this is what we can read, this is what we touch, but there is also the reverse of the object, the cast, the residual, the subtractive, the negative which can give witness to the invisible. Perhaps this is a virtue of the virtual, perhaps this is the substance of the unseen, of the passionate narrative, of silent voices, or the final word.

Both the Main Hall interior and the canopy/loop define versions of this invisible. The hall is the cast of a vast self-intersecting knot, itself a precise tangle along the way, itself perhaps only properly fulfilled by the throng of its occupation. The canopy/loop is a visible sliver, a physicalapproximation of an otherwise invisible thread now continuously changing direction.

Howard Raggatt

Credits

- Project

- National Museum of Australia

- Architect

- ARM Architecture

Australia

- Project Team

- Craddock Morton, Peter Wright, David Waldren, Garry Eggleton, Philip Johns, Steve Ashton, Howard Raggatt, Ian McDougall, Robert Peck, David Waldren, Ken Bool, Alan Ball, Allan Flynn, Andrew Hayne, Antony McPhee, Catherine Evans, Chris Reddaway, David Homburg, David Murrell, David Pryor, Doug Dickson, Ivo Tanevski, Gustav Kroyherr, Jacinta Vines, Jan van Schaik, Jesse Judd, Lilliana Andjelkovic, Lorenzo Gelati, Natalie Plumstead, Neil Masterton, Nevena Bresoska, Nikolas Koulouras, Paul Dash, Paul Minifie, Peter Ryan, Poh Raggatt, Rod Newton, Sally Hieatt, Simon Sheil, Sue Adams, Sue Dove, Tim Wright, Richard Weller, Tom Sitta

- Consultants

-

Access consultant

KLCK

Acoustics Bassett Acoustics, Eric Taylor and Associates

Audiovisual consultant Canberra Professional Equipment

Building services Tyco International

Civil engineers Young Consulting Engineers

Communications engineer Diverse (Tyco)

Exhibition designer Anway and Co

Exhibition joinery fabrication Classic Resources, Designcraft, Stag Shopfitters, UTJ

Fire engineer Bassett Consulting Engineers, Ove Arup

Glazing and facade systems G James

Hydraulic engineer Young Consulting Engineers

Landscape Urban Contractors

Landscape architect Room 4.1.3

Lighting Vision Lighting

Mechanical and electrical engineers Bassett Consulting Engineers

Object install Thylacine Exhibition Preparation

Project management Lendlease

Project manager TWCA, Acton Peninsula Alliance

Quantity surveyor Slattery Australia, Donald Cant Watts Corke, Wilde and Woollard

Security and BMS Contractor Honeywell

Security engineers Honeywell

Structural engineer Ove Arup and Partners

Structural steel National Engineering

Traffic engineers Ove Arup and Partners, Hughes Trueman Canberra

- Site Details

-

Location

Lawson Crescent, Acton Peninsula,

Canberra,

ACT,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Commonwealth Government of Australia