A multidisciplinary team of Australian architects and engineers are behind the design of a lightweight, prefabricated and easily assembled school building that has been rolled out in more than 30 earthquake-prone locations across Nepal, which was devastated by severe tremors in 2015.

Led by David Carolan, director of Sydney-based engineering firm Taylor Thomson Whiting (TTW), the team was rewarded for its efforts last week when it received Good Design Awards in both the architectural and engineering categories.

The project has been an unequivocal success, with more than 20 classrooms built to the now award-winning design across five different schools, including one school for special needs students in the village of Garma.

New school building in Garma, Nepal.

Image: courtesy Australian Himalayan Foundation

Architect Ken McBryde, director of Sydney Architecture Studio, came to the project in a roundabout way. He had travelled with his wife to Nepal a month prior to the earthquake to investigate helping with the preservation and remediation of the habitat of the Nepalese red panda.

He remembers being taken by the “level of local creativity” that was evident in the homes and other buildings in the country’s small alpine villages.

“Fast-forward a month or two,” he said, “and thousands of buildings were shaken to the ground.” The earthquake in April 2015 killed 9,000 people, made hundreds of thousands of people homeless and disabled vital infrastructure.

“I also learnt that international aid organizations rushed to help,” after the earthquake, he added. “And then when they turn up they can’t do anything. There’s no infrastructure. Nothing is organized. So they eventually [had to] give up and go home.”

In the meantime, David Carolan was seeking ways to improve the situation. Familiar with McBryde’s work on cyclone-resistant homes in Vanuatu and in remote Indigenous communities, Carolan reached out to McBryde about collaborating on a design for a lightweight, earthquake-resistant school that could be easily and cheaply built to replace those that had been lost.

The primary requirement for the design was that it was lightweight. “The heavier something is the more it attracts earthquake loads,” explained McBryde, who drew on experiences designing in earthquake-prone New Zealand to inform the work.

Carolan proposed using conventional, cold-rolled steel stud frames – “the type of construction that you can see, every day of the week, when you have a look […] on the fringes of Australian cities,” McBryde said.

New school building in Garma, Nepal.

Image: courtesy Australian Himalayan Foundation

Working under the auspices of the Australian Himalayan Foundation, the team, composed also of architects from Hassell who worked mostly after hours, drew up a design that came in “bits that you can carry up the hill on your back.”

McBryde’s prerequisite for being involved in the project was that it would have to be informed by local culture and perspective.

“As long as we can make it in a way that’s meaningful for locals,” he said. “You can use technology to solve a technical issue like earthquake design, but you need to engage the community and the building needs to belong to its vernacular.”

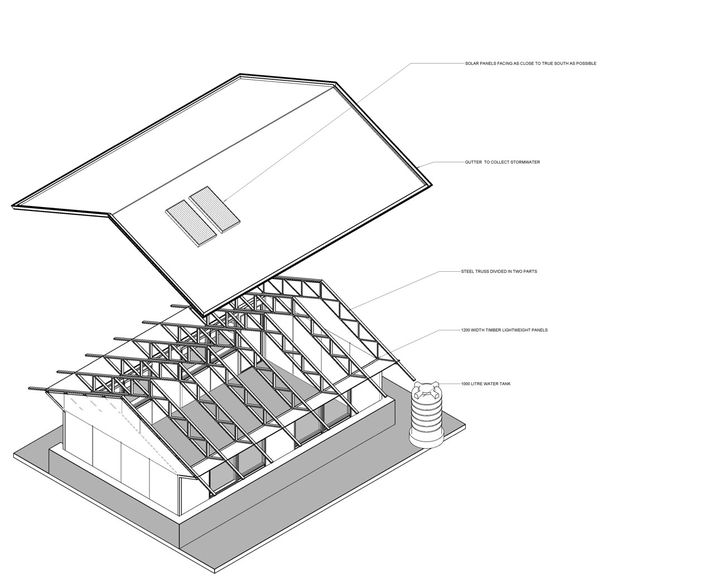

3D exploded view of the school design.

Image: courtesy Ken McBryde

This manifested in a key part of the design – a locally laid stone wall that sits around the perimeter of the buildings and rises to the height of the window sill. While referencing the local building vernacular, the walls are less likely to be lethal in the event of a major earthquake. “If those stones shook to the ground in an earthquake they would be so low they wouldn’t fall down or if they did they wouldn’t hurt anyone,” explained McBryde.

“A lot of the people were injured by stone walls collapsing. The locals build stone walls by shoving mud [in between the rocks], like a grout. But they stop doing it when they can’t reach. If they do it properly it’s quite an okay system, but they hadn’t had a big earthquake since the 1930s, so that memory [of how to construct the wall adequately] gets lost.”

While the stone walls reference local building practices, they also serve a key function: stopping the thin, lightweight frame from collapsing in a stiff wind.

McBryde said the design couldn’t “rely on a concrete slab to hold the frame down because we didn’t know what kind of quality of work will [be done in its installation].” The buildings are then clad in “whatever is culturally appropriate.”

The school’s other features include rainwater tanks, oversized eaves that provide shelter in the rainy season and gables that can be customized by local craftspeople.

Annotated sketch of the school design.

Image: courtesy Ken McBryde

Quoting Carolan, McBryde noted that while the method of the schools’ construction is “completely standard” by Australian standards, the methods used are still “forty years ahead of the Nepalese Department of Education’s thinking.”

McBryde said that efforts were ongoing to “give the designs away to whoever wants it,” but issues around professional liability made this a complicated endeavour.

The project was led by the Australian Himalayan Foundation and Thomson Taylor Whiting. McBryde headed a design team that included Guy Wilkinson and Suleiman Alhadidi (team leaders), Jay O’Dwyer (architect) and Ben Charlton and Benjamin Li (architectural assistants). The project was masterplaned by Neill Johanson, Ben Nemeny and Tom Singleton of Davenport and Campbell. Architect and mountaineer David Francis also worked onsite in Nepal.