KEVIN BORLAND: ARCHITECTURE FROM THE HEART

Doug Evans (ed) with Huan Chen Borland and Conrad Hamann. RMIT University Press, 2007. $45.

While working in the office of Borland and Brown in the early 80s, I was struggling with the design of my first commission. My attempts, while enthusiastic, reeked of fear and I was procrastinating by thumbing through a tome on Japanese architecture.

Kevin, noisily munching on an apple, glanced over my shoulder, bent close to my ear and said, “You won’t find it in a book, digger.” Kevin saw the design process as intuitive and sensual and not one to be overly intellectualized.

I pondered his comment as I cleaned up remnant apple cores and resolved to confine book-looking to the privacy of my home.

This was early 1981, when Kevin was about to begin his tenure as Professor of Architecture at Deakin University. He was at the end of a phase of his career that began in the early 50s, and this roller-coaster ride was, to his mind, coming to an end.

He had unsuccessfully submitted Clyde Cameron College (1975–77) to the RAIA Awards. This lack of recognition by his professional peers indicated that the architectural wheel was turning and he was considered passé in comparison with the supposed wit of postmodernism; the profession was looking for new heroes.

The book Kevin Borland: Architecture from the Heart by Doug Evans (ed) with Huan Chen Borland and Conrad Hamann offers a compelling portrait of Borland as a passionate individual who stood as an architectural hero to many. The format is unusual in presenting a wide range of contributions. The comprehensive essay by Evans, which provides an overview of Borland’s life and works, is accompanied by tight and telling critiques from Conrad Hamann with project drawings by Huan Chen Borland.

Interposed between these more traditional reviews of Borland’s oeuvre are reminiscences from former contemporaries, colleagues, clients and friends.

The resulting book sits between biography and architectural critique, with a cocktail of opinions and reviews that give a rounded vision of Borland the architect. His children provide the most poignant insights.

In particular the eulogy by Polly Borland reveals great love and respect but also a sense of pain. Kevin’s great passions sometimes obscured the sweet mundane; he didn’t stop to smell the roses. The children speak of their father’s personality as a mix of confidence, bluff and frailty. It is perhaps this picture of Borland as a warrior father with chinks in the armour that allows us to see the body of work as the product of intense human endeavour and not just a professional résumé.

There may be a need in the future for a comprehensive survey of all Borland’s work. That should not diminish the significant contribution of this monograph. It skilfully combines scholarship with a mapping of the emotional topography of Borland’s architecture. If you want an insight into the life and architecture of Kevin Borland, you will fi nd it in a book, this one.Andrew Hutson

THE THIRD SKIN: ARCHITECTURE, TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT

By Scott Drake. UNSW Press, 2007. $59.95.

My great privilege as a student was to be taught architectural science by Steve Szokolay. A confessed maths nerd, I thoroughly enjoyed applying algebra to the study of environmental impacts on architecture, and in particular to the comfort zone of the lightly clad, sedentary fi ftieth percentile who dwelt therein. Reyner Banham’s book, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment, however, set a quite different corner of the brain a-tingle, as it elegantly recounted the pursuit of environmental control within the broader tapestry of human endeavour. There were two clearly diverging paradigms of research within the university – words and numbers, equations and analogies, histograms and histories, footnotes and superscripts – the literate and the numerate, the library and the laboratory.

Scott Drake is a literary fellow, trained in the humanities but driving directly into the territory formerly inhabited solely by numbers folk.

He is a crisp writer, with a seemingly effortless ability to describe complex phenomena concisely and with precision. The Third Skin regularly distils issues as arcane as sanitary plumbing or as complex as theatre acoustics into one or two pages. Pithy paragraphs are generally supported by pertinent footnotes, a thorough index and comprehensive links to further reading. A number of contemporary local buildings are cited, though not illustrated or referenced, and the currency and pertinence of these examples will surely fade with time. Rare lapses in brevity (the decibel remains enigmatic for four pages) can usually be traced to a determination to express, in words, ideas that could be expressed more succinctly as graphs or illustrations.

On the other hand, the two mathematically expressed studies in the appendices are so cryptic that they are little more than a sketch of the quantitative method.

This introduction to architecture, technology and environment is clearly written and reasonably priced, but it is less clear how the reader should use such knowledge.

An unambiguous understanding of a phenomenon is only the beginning of useful knowledge, and should naturally lead to a curiosity about why, or how, or where this information could or should be applied. In this regard, The Third Skin does not replace texts like Szokolay’s Introduction to Architectural Science as a standard reference. It does, however, provide a broadly accessible introduction to the topic and is a reliable companion for those pursuing more detailed study in the scientifi c mode, in order to fully understand and apply these principles.Associate Professor Peter Skinner

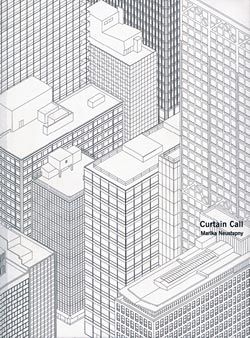

CURTAIN CALL: MELBOURNE’S MID-CENTURY CURTAIN WALLS

By Marika Neustupny. RMIT University Press, 2006. $33.

Curtain Call is the result of a cycle of RMIT urban research electives, in which students participated in guided research and employed study documentation methods. The book is a concentrated study of office building curtain walls built in the 1950s and 1960s within the central business district of Melbourne. It is not specifically a handbook for curtain wall designers. Rather, as Marika Neustupny explains in the preface, the study looks at how the curtain wall surface of a particular building is perceived and understood.

There is a foreword by Hannah Lewi on the importance of fully documented case studies for future historical and advocacy work, and an essay by Marika Neustupny on the relationships between city and inhabitants created by a curtain wall.

She considers how the layout of the city might influence the design of curtain walls, the influence of site proportions and orientation, and the social and historical elements that affect and are affected by the design of the curtain wall plane. The book ends with an essay by Rohan Storey on the developments of curtain wall design in Melbourne between 1955 and 1975.

The majority of Curtain Call, however, is focused on 17 carefully documented case studies, and this is where the main interest lies. The case studies aim to highlight the complexity of thinking that surrounds curtain walls. Elevations and plans, photographs, facade drawings, details and axonometric drawings represent each of the buildings. The construction detailing and fabric arrangements are examined and questioned in succinct descriptions.

The case studies are presented in such a way that comparisons between the buildings can easily be made, and the use of facade drawings in conjunction with photographs strongly identifies the patterns of the curtain walls. The photographic studies are by Peta Carlin, who collaborated with Marika Neustupny on teaching the urban research elective series. A survey index of 47 significant mid-century curtain walls in Melbourne can be found at the back of the book, with reference to relevant publications, along with a map locating the case studies.

This small book is the product of an evolving research project and is not meant to be an exhaustive information guide to curtain walls. In this context Curtain Call effectively acts as a general tool for designers, historians and theoreticians, while expressing the strong interest in these buildings that the author and collaborators share.

Katelin Butler

CRISIS OF THE OBJECT: THE ARCHITECTURE OF THEATRICALITY

By Gevork Hartoonian. Routledge, 2006. $118.

Gevork Hartoonian’s Crisis of the Object offers important new insight. It is a work of genuine architectural theory that questions our understanding of the spectacular global successes of the contemporary neo-avant-garde, and in particular the work of Peter Eisenman, Bernard Tschumi and Frank Gehry.

The nature of this neo-avant-garde work as “spectacle” is subjected to Hartoonian’s vivisection. Spectacle is understood as an excess or aestheticization of architecture, an almost exclusive focus on the elaboration of the surface for flamboyant and immediate gratification of fetishist desires. Against this, Hartoonian juxtaposes Gottfried Semper’s notion of theatricality in architecture. The idea is complex and highly developed by Hartoonian, but the most compelling aspect is anonymity: “Central to the idea of theatricality is the possibility of embellishing the constructed form to the point where the art form remains anonymous.” There is a differentiation here between the “art form” – that is, the purely artistic expression of the architecture – and the “core form”, understood as the physical making of the building, its materiality and construction.

The idea of anonymity in this context is very interesting and powerfully juxtaposed against what we could call the individual will to spectacle, which Hartoonian suggests can be naturally restrained or mediated in Semperian theatricality. “Theatricality is the flesh of construction whose thickness speaks for the invisible presence of the dialectics of seeing and making, that is the way a building relates to its site, framing a constructed space and opening it to the many horizons of today’s culture.”

Hartoonian makes reference to the inherent anonymity in poetry, and in particular Charles Bernstein’s discussion of theatricality in poetry and the way the poetic message is understood in an indirect way through the play of the visible and invisible. In architecture this can be understood as the play of concealing and revealing materiality, structure and construction for expressive or poetic intent.

He suggests a way out of the prevailing culture of spectacle, with an insightful interpretation of Semper’s idea of theatricality. The book’s title refers directly to André Breton’s essay of 1932, and Hartoonian draws on the original possibility offered by the surrealists, a smooth transition of the traditional object into the new – as opposed to the Modernist transformation and dissection of the object through an unqualified belief in technology. This is the Crisis of the Object to which the book refers.

Hartoonian is truly appreciative of the critically creative achievements of the American neo-avant-garde – Eisenman, Tschumi and Gehry – dedicating an analytical chapter to each. However, despite his clear admiration for their work, Hartoonian is not caught in the ideological net woven by these architects and authors, but embarks on a critical demystification of the work and texts. Equally, he does not attempt to devalue neo-avant-garde achievements in the process. This kind of rigorous demystification is rare, and Hartoonian is in a sense meeting the tough line that Manfredo Tafuri plotted in calling for criticism to be the critique of hidden ideologies within architecture.

There is so much in this book, so many interesting asides to Hartoonian’s central argument. For example, his observations on the accommodation of contemporary architecture to the nihilism of technology, or the limitations of the digital studio, or indeed his proposition that we re-examine the original avant-garde practice of montage as a possible strategy against the so-called false mirage of the architectural spectacle.

Crisis of the Object is revealing and insightful, and worth the concentration Hartoonian demands from the reader.

Richard Francis-Jones