national indigenous housing guide: improving the living environment for safety, health and sustainability

Australian Government Department of Families, Community and Indigenous Affairs, 2007. 328pp. Free.

This is the third edition of a critical resource for all those involved in the design, construction and maintenance of housing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with “a particular focus on providing and maintaining the ‘health hardware’ that supports a safe and healthy living environment.”

There are only a small number of people working in this unglamorous but vital area and many are not architects. The book’s intent is to ensure that these people, be they tradespeople, draftspeople, building designers, specifiers or those new to the area, have base principles against which to assess their design decisions and avoid past errors in housing design and specification.

This intent underpins both the layout and structure of the book and the information within it – it is essentially a technical manual that identifies key design issues and proposes possible solutions.

The contributors are numerous and include community members, environmental health workers, architects and others, but the core information is based on the Fixing Houses for Better Health (FHBH) programme developed by Paul Pholeros and his organization Healthabitat.

Paul Pholeros sees the guide as a dynamic shared field of knowledge, which is reviewed and updated every two years. His vision is for more flexible, web-based documents to be established, and for actual examples of problems and solutions to be available online.

This updated version is a considerable improvement on the second edition (2003). It has a more user-friendly structure, expanded information sections and updated statistics from FHBH’s ever-growing database.

The guide has four main divisions: Safety, Health and Housing, Healthy Communities and Managing Houses for Safety and Health. Within each division, sub-topics describe “life threatening safety issues” and the “Nine Healthy Living Practices”. This structure is intended to “assist in the decision making about spending priorities on housing design, construction and maintenance to achieve better health outcomes.”

The issues presented are rated to describe the extent and quality of information available, with the intent that practitioners will add to the knowledge base. The sections are then described in areas relating to design, on-site quality control, maintenance, survey data and standards, and references. This structure is extremely useful and will form a robust framework for the ongoing expansion of the guide.

The guide does not cover all issues relating to Indigenous housing; however, within its focus area, it is the most valuable knowledge base currently available and therefore essential reading for anyone working in this specialized area.

Finn Pedersen

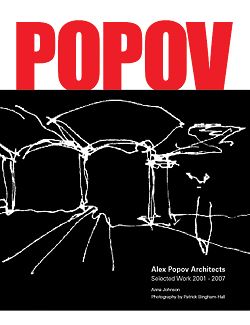

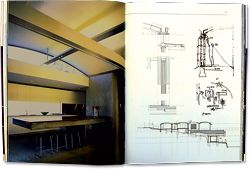

alex popov architects: selected works 1999–2007

Text by Anna Johnson, photographs by Patrick Bingham-Hall, Pesaro Publishing, 2007. 440pp. $70.

It must be difficult to determine the appropriate tone for a contemporary Australian architectural monograph. How to satisfy the educated architectural elite, hungry for serious architectural commentary, while simultaneously making work accessible to the broader public? Pesaro’s series of monographs have often erred on the populist – a surfeit of glossy imagery accompanying essays penned by supporters and an absence of comprehensive architectural documentation. But the series has had a critically important role in bringing the work of small Australian practices to the attention of a broad cultural audience. The importance of this should not be underestimated in a nation where the general level of understanding and cultural appreciation of architecture is severely limited.

Pesaro’s recent monograph on selected work of Alex Popov Architects between 1999 and 2007 strikes a more comfortable balance between its architectural and lay audiences. The work is introduced in an essay by Anna Johnson, who takes time to explain the development of the Sydney and Pittwater schools and the role that their particular response to landscape has had in the formation of Sydney’s architectural identity. Johnson then presents a reading of Popov’s work as one of opposition, asserting that “his response is not mimetic, it does not attempt to merge into or become one with the context, but rather, it establishes a relationship through juxtaposition and contrast.”

The work’s piercing clarity and unapologetic interest in legibility, solidity and monumentality has long confounded critics and observers versed in more fashionable contemporary themes of complexity and formal sophistry, who have tended to dismiss it as conservative. Johnson’s challenging of this reading is astute and timely.

The latter parts of the essay are less comprehensive, but briefly touch upon themes of additive and archetypal architecture, community and connection, the interior, and drawing. The volume predictably features the sumptuous photographs of Bingham-Hall, but also includes a range of architectural drawing types. Popov’s evocative sketches headline, but are accompanied by refined presentation drawings and excerpts of details and documentation drawings. Also distinguishing this monograph is the strong presence of multi-unit housing projects. It is important that this work starts to get an airing with a mass audience, whose suspicions of developer-driven multi-unit housing need to be balanced by exposure to architecturally sophisticated housing projects of this type.

Pesaro is certainly refining the balance between architecture and populism as its series develops. One hopes that this can be interpreted as a sign of the emergence of a more particular architectural interest they are detecting in their wider readership.

Laura Harding

Sydneysider: an optimistic life in architecture

Don Gazzard. Watermark Press, 2006. 232pp. $50.

Architects rarely write about their careers from a biographical point of view. Most often, they reflect on their design philosophy with marvellous selectivity, or they write with an earnestness that readers struggle to find interesting. Many leave the task to others, so their professional lives are suitably gilded with the pedigree of other voices, and personal involvement and words (nay, admissions) discreetly distanced.

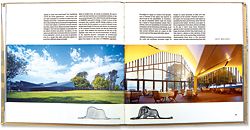

Not so in Sydneysider: an optimistic life in architecture. Don Gazzard writes about his life in architecture with refreshing frankness and without rancour. He also writes well – the book is a pleasure to read. We gain an image of a multidisciplinary practitioner, an architect with interests in urban design, urban planning and urban activism. Gazzard freely admits that this broad range of expertise has meant that, at times, his facility to perfect certain design ideas was limited. However, this humility underscores Gazzard’s point. He believes in the importance of the architect’s ability to engage with a strategic overview of the city and, at times, to take small steps to realize larger visions of, or make correction to, what the city might become.

Gazzard’s organization of the seminal Australian Outrage exhibition in 1964 (and the accompanying book); his prophetic designs for new urban space at Circular Quay, 1962; his involvement in the design and pedestrianization of Martin Place, Sydney; and the community activism that led to the conservation of nineteenth-century Paddington are examples of a broader contribution to the discourse and practice of Australian urbanism.

However, Gazzard is clearly also a designer of great talent and the book reveals many (but not all) important works. The Herbert House at Hunters Hill (1960), the Kingsdene estate and the Ellesmere display house at Carlingford (with George Clarke, 1961), the Wentworth Memorial Church at Vaucluse (one of the great Australian church designs of the 1960s) and his firm’s resort architecture and airport terminals in Sydney, Nadi and Coffs Harbour all show clarity of idea, place and purpose. This hints not only at his educational background in engineering, but also at his experience working with Harry Seidler (1951–54), where he cut his architectural teeth on the design development, engineering computations and documentation for many of Seidler’s early houses.

But Gazzard was no clone. His own house in Paddington (c.1975) is a brilliant solution to an historic streetscape, a solution that his former employer would not have countenanced – a strongly contextual urban response but nevertheless a house strictly within the modernist firmament. However, what is most interesting about this book are Gazzard’s descriptions of his lesser-known but equally significant housing and institutional buildings in the Pacific Islands and Laos, and his work with Aboriginal communities in Western Australia, Rooty Hill and The Block in Redfern. Again we are shown a practitioner happy to collaborate with and acknowledge others (and also his failures), one ready to engage with the larger issues of habitation and cultural negotiation in challenging environments.

Throughout the book Gazzard relieves the reader with sections on how architects work, covering themes such as design research, low energy, loose fit and long life. Here Gazzard gives us commonsense lessons in making architecture. The chapter “Riding the Tiger” is an especially candid lesson in architectural practice, the highs and lows of the design and documentation process. It makes terrific reading for students and clients as well as fellow professionals.

This book reveals Gazzard’s fondness for his profession and its art, and for his city, Sydney – a place that requires not just its landscape but also its urbanism to be learnt, lived and loved.

Philip Goad

Terroir: cosmopolitan ground

Scott Balmforth and Gerard Reinmuth (eds). Faculty of Design Architecture and Building, UTS, 2007. 200pp. $65.

Terroir pursues a singular practice model. The three directors – Scott Balmforth, Richard Blythe and Gerard Reinmuth – are based in three cities – Hobart, Melbourne and Sydney – and all are entrenched in the architecture schools of their respective cities. Terroir describes itself as a critical practice. It has close ties to philosophers of architecture and to artists, it employs staff dedicated to research, and it actively examines the potentials of a distributed office and produces critical works of architecture.

Terroir: Cosmopolitan Ground presents a concise record of these diverse interests. The book is structured by three horizontal bands that run simultaneously through the publication, suggesting equal weight be given to the office’s critical practice and its project output. The upper band presents a series of essays, the middle band contains projects presented in chronological order, and the thin lower band accommodates plans, diagrams and quotations.

The essays include excerpts from two symposia: Cosmopolitanism and Place: The Designs of Resistance, and the Terroir Symposium, as well as essays by Jeff Malpas and Marcelo Stamm from the School of Philosophy at the University of Tasmania. The projects range from the first completed in 2000 – several houses and a Masonic hotel in Hobart – through to recent work, notably the short-listed competition entry for the Prague Library and the hotel at The Hazards in Tasmania. In between are various projects, proposals, competition entries and installations. An early unbuilt project for a library and gallery in Canberra for a private client is particularly intriguing, encompassing many of the tools and tropes that the practice has developed in the following eight years – the line in the landscape that traces landscape and envelope, the cranked wall, the intense interiority.

Images are the dominant means of representation. Photographs of models, digital images, reference images and photographs of the completed buildings are given precedence over plans and the occasional section or elevation, which are printed at a squinty size. This strategy is consistent with a statement by Andrew Benjamin in the excerpt from Symposium One, that images are only interesting as a portrait of production. It is evident in this monograph that production is keenly monitored and critiqued by Terroir. This is manifest in the frequent reference images scattered throughout. It is unusual to see references presented alongside projects in an architectural monograph, and here it is especially revealing of the workings behind many of the projects – the stealth bomber at The Hazards, an Eduardo Chillida sculpture for the Liverpool Crescent House, the fissures and tears in the photography of Bill Henson that opened up possibilities of how light might enter a spa, a painting by C. W. Eckersberg that led to an attitude towards a chalk cliff face.

The lack of complete documentation of the projects through plans and sections is occasionally frustrating; there is a great deal of complex spatial manipulation at work that is difficult to discern. However, even without this information, this is a dense book, which successful records the pursuits of the practice.

Marcus Trimble