<b>REVIEW</b> Sandra Kaji O’Grady

<b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> Floto+Warner studio

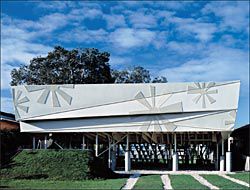

The front elevation of the prefabricated house, with its laser-cut plywood facade.

Detail of the diagonal web of structure underneath the house. Holes have been cut into the joists for storing surfboards and wetsuits.

The windowless front facade is detailed with a large flower motif taken from bikini designs.

The open rear elevation, with a set of bleachers reaching down into the backyard.

The folded planes of a bedroom interior.

Facade detail with undercroft structure.

Undercroft structure.

A surfboard stored under the house within a joist.

Looking up the entrance stair.

The top of the stair and dining area seen from the dining deck.

The highly faceted planes of the living area.

In my attempts to assemble criteria for evaluating architecture, both as a critic and as a teacher, I often return to Sol Lewitt’s “Sentences on Conceptual Art” (1968). Sentence 32 states: “Banal ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution.” Sentence 34 proposes: “When an artist learns his craft too well he makes slick art.”1 With the craft of making buildings in the hands of others, beautiful execution is so improbable that it has for many architects – and also those who judge their work, be they clients, critics or other architects – become the highest ambition and measure of success. I am not advocating sloppiness or some sort of architectural equivalent of Art Povera, but am unsatisfied by extraordinary displays of control over details and joints in projects that remain conceptually banal.

While the refined architectural project may contribute a great deal to the lives of its immediate clients and physical locale, projects that make a broader cultural contribution are also necessary.

Buildings that make us wonder and see the world anew are too rare. So too are projects that alter our assumptions about the limits of the discipline and demonstrate alternatives to conventional solutions.

In this context the Parish house, or Burst*003, is refreshingly ambitious.

Situated in North Haven on the north coast of New South Wales, the house is the work of the New York-based partnership of SYSTEMarchitects – Jeremy Edmiston and Douglas Gauthier – in collaboration with Robin Edmiston and Associates.

It is the first realization or prototype of a prefabricated, affordable housing system that they plan to launch in the American market as “Burst”. Mass-produced housing from prefabricated components is an old ambition. The history of architecture is replete with prototypes thwarted by contextual forces outside the architect’s control – for example, Suuronen’s plastic Futuro house of the 1970s, a victim of the fuel crisis.

To embark again on this path takes a stubborn optimism and a willingness to embrace a range of issues more akin to industrial design – including marketing and competition, packaging and delivery, as well as questions of variation and consistency in the product range.

The prototype house is achieved most elegantly here using pieces of laser-cut plywood brought to site on a single flat-bed truck. What is groundbreaking is that the aspiration for prototyping has been coupled with a formal complexity and potential for customization supported by new computer-supported design and manufacturing tools. The duo has been working for a decade now on the potentials for interlocking structures of smaller planar parts. Communicating the fabrication and assembly of 1,100 non-identical pieces required atypical forms of documentation, and with that, an original approach to thinking through how to design and realize that design. Laying out the plywood pieces was achieved using the software program used in garment manufacture with very little wastage. While high technology is used throughout the design and manufacturing process, low technology is intentionally employed for assembly and for maintenance. Assembly requires fewer skills but intense cooperation and concentration. The building was put together by architecture students in something akin to a barn raising. The architects are fond of this image, yet recognize that the design’s reliance on numbers of enthusiastic and sympathetic cheap labourers will make it less desirable for some.

Accordingly they are working on a solution that packs flat and unfolds.

The project’s technological innovations are only half the story. Socially and formally, it recalls a type of weekender near extinction in Australia – the fibro shack on stilts whose rudimentary amenities demand that its occupants forgo the cosseted habits of their lives in the city. For most of the twentieth century the Australian beach shack and its counterpart in New Zealand, the bach, facilitated days spent outdoors unconcerned by tidiness, propriety or the display of social or economic status.

Summer holidays functioned like carnivals in medieval Europe – a pair of speedos (delightfully referred to in Sydney as budgie smugglers) and bedrooms furnished with mismatching bunk beds being a great leveller. In New Zealand, the active mythologizing of the bach – among architects as well as in popular culture – has gone some way to preserve the idea that retreat from the constraints and stresses of the city is furthered by the simplicity of one’s shelter. This seems lost in Australia, where beach houses have become luxurious anticipations of “sea change” and comfortable retirement. The Parish house reinvents the beach shack for a family with three young children in a church community where gatherings can be large and informal. In materiality and expression it conveys the joy of beach life and operates as an armature for life devoted entirely to recreation – even its small living space has been given over to table tennis. The rear facade of the house overlooks a garden with the proportions of a basketball court and reaches down to it with a set of bleachers perfect for games and impromptu family theatre. The potential for play continues in the space underneath the house, where the diagonal web of structure imbues a gothic, otherworldly quality. Cut into the joists are holes for storing surfboards and wetsuits and it is easy to imagine this undercroft gathering bicycles, dogs and teenagers during the holidays.

The Parish house sits on an unprepossessing flat allotment without views in a cul-de-sac of brick veneer suburban project homes. It was the first and only house in the street to meet new flood requirements for buildings in the area. Raised above ground on stilts, it was always going to be anomalous in the context, and it does not shirk from this. It greets the neighbours with a windowless, folded facade lightened by a large flower motif taken from bikini designs. The faceted facade suggests only a little of the visual complexity of the interior. The plan is quite simple – a wing of bedrooms to the street and living spaces to the rear garden – but the volume has a continually changing section, metaphorically modelled on the wave. The scale of elements varies to achieve densely faceted planes in the living room ceilings and walls, with broader folded planes in the bedrooms. Highly differentiated, almost painterly light qualities are achieved across the house. The architects talk about their interest in chiaroscuro, of using a full range of light and shadow to achieve dramatic contrast. The potential for this visual complexity to overwhelm is countered by a single flat cream paint finish used externally and internally.

The success of Burst as a kit home is not yet known. Models of innovation and prototyping developed in management and humanities are not well understood in architecture. There is not a clear path for the architects to follow to ensure the successful transition from prototype to a product with market share. Design quality is understood in other arenas of mass production as a value that can be used in marketing, yet most kit homes compete solely in terms of cost, adaptability and availability.

There are not brands of designer kit homes recognized in the market as there are brands of furniture and homewares. The Burst House may change that. That it even attempts an alternative to the narrow choices of luxury, unique weekender or generic suburban brick and tile cottage is admirable.

In this first implementation of the system, it is a success. In form, social type and technique its ambitions are thoroughly integrated and bravely carried out.

DR SANDRA KAJI-O’GRADY IS ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR AND HEAD OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, SYDNEY.

BURST*003 HOUSE, SYDNEY

Architect SYSTEMarchitects —principal architects Jeremy Edmiston, Douglas Gauthier; project team Sarkis Arakelyan, Amber Lynn Bard, Ayat Fadaifard, Sara Goldsmith, Henry Grosman, Kobi Jakov, Joseph Jelinek, Ginny Hyo-jin Kang, Gen Kato, Yarek Karawczyk, Ioanna Karagiannakou, Tony Su. Consulting engineer Buro Happold.

Project engineer Cristobal Correa.

Client Andrew Katay, Catriona Grant.

LOCAL CONSULTANTS Site architect Robin Edmiston and Associates. Site engineer Peter Marcus.

Site architect for SYSTEMarchitects Chris Knapp.

CONSTRUCTION Laser cutting Grifco International Inc.

Frame assembly team Sarkis Arakelyan, Newcastle University architecture students: David Arnott, Andrew Cavill, Justice Chengeta, Louisa Gee, Ned Haughton, Simon Hayward, John Jones, Jonathon Mentink, Shaun Purcell, Jo Redden, Justin Spraull, Ksenia Totoeva.