REVIEW BELINDA BRITO PHOTOGRAPHY TYRONE BRANIGAN

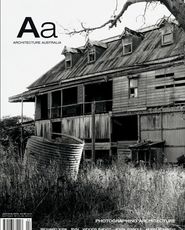

The stark juxtaposition of old and new on the building’s south-west corner, the most visible part of the site.

The northern tip of the project.

The key components of the intervention are the new foyer stair and the highly articulated steel-framed box atop the original warehouse fabric.

The verandah space of the rooftop extension.

Looking across the upper level landing.

The elegant and highly detailed stainless steel pin-and-cable system which suspends the robust stairs from the new steel roof structure.

The foyer with the new centrepiece stair. The massive steel frame supporting the roof canopy is strutted to the warehouse wall beyond.

Detail view of the foyer with its layered planes and contrasting elements and structures.

Detail view of the foyer with its layered planes and contrasting elements and structures.

WITHIN THE INNER city precincts of Sydney, limited opportunities for new development and continuing demand for “age value” mean that abandoned industrial buildings are now prime real estate and ideal sites for contemporary architectural renovations. Warehouses, silos and factories are featured regularly in the popular press as desired containers for urban life. Generous floor areas, high ceilings and industrial detailing have become fashionable must-haves, analogous to a media-hyped warehouse lifestyle. Regrettably, however, many warehouse conversions are unremarkable. Economic rationalism produces circumstances that dilute the spirit of this typology. Internal space is carved and divided and divided again, creating higher densities and anticipating higher returns. Residential and commercial spaces are often inserted into industrial shells with ineffectual impact. A recently completed warehouse conversion by Woods Bagot in Ultimo avoids such reductions.

Contrasting new and old is a common strategy in the production of renovations and conversions. In the Mountain Street development, Woods Bagot takes this approach to its extreme, starkly contrasting the existing fabric with a highly refined new insertion.

Oppositions are emphasized and architectural expression is heightened, confirming the valued qualities of the old while further invigorating the spatial qualities of the new. The original masonry building, formerly a goods bulk storage facility for Marcus Clarke and Company, occupies its entire triangular site, with three street facades along the perimeter boundary. Constructed in 1909, it is solemnly proportioned. Regular vertical bays articulate the facade and counterpoise the horizontal solidity that anchors it to the site. Neither remarkable nor particularly distinctive, it is similar to many of the existing warehouses within the immediate vicinity.

At the corner of Mountain and Kelly streets, the most visible part of the site, the stark architectural juxtaposition of old and new announces the building’s converted status. The intervention unfolds from the new street level canopies, through to a narrow vertical incision of glass, to the crowning of the warehouse. Indeed, the rooftop addition – a highly articulated steel-framed box – is the most prominent feature of the new works. Transparent and skeletal it hovers above the brick parapet, supported not by the massiveness of the masonry facade but by a steel column system that extends internally from deep within the original structure. Glass facade and brick wall are contiguous, precisely aligned. Although structurally divergent, the rooftop addition is attentive to the robust proportions that characterize the original building and the configuration of new columns and mullions echo the divisions that regulate the original fenestration.

Programmatically the conversion is uncomplicated. At each of the three levels, the generous internal proportions of the original warehouse now accommodate commercial spaces and associated amenities. Within these areas the preservation of the industrial character has meant minimal intervention: original proportions and open floor plans are maintained. To meet local council planning requirements, a portion of the ground floor is allocated to parking and its floor space redistributed to the rooftop. A new foyer space, accommodating lift, stair and associated services, is located within the warehouse, accessible from Kelly Street. A retail/cafe space activates the street frontage and takes advantage of pedestrian and park amenities along Mountain Street.

While the warehouse character appears as a given, the pursuit of the original was an arduous and costly exercise. Remnants of the original fabric – face brick walls, ironbark timber columns and herringbone ceilings – were restored during a two-year process of demolition, preservation and reconstruction. Significant work during this period included rebuilding the existing parapet due to structural failure, as well as modifications to the original footing system. To support the additional level, unsuitable ground conditions and increased loading to existing columns required that steel piles be inserted and bedded to rock at each column point. Ironbark columns were removed and reinstated, connected to the new foundations via large industrial steel stirrups.

A committed collaboration between parties (builder, architect, client and structural engineer) was crucial, particularly during the process of demolition and reconstruction when many of the original building’s structural weaknesses were discovered.

Such commitment to the preservation of the existing fabric came despite the lack of a heritage or conservation order on the site, with the client under no obligation to retain any feature of the original. Feasibility studies determined that the most financially viable option would be to raze the structurally unsound brick edifice and rebuild. However, the client’s desire for the coalescence of old and new remained resolute. Translated architecturally, this fuelled the strategy of contrast. In rebuilding, the aim was not to replicate but rather to emphasize and validate the romantic qualities of the industrial.

Preservation and intervention are interdependent here – in their markedly different expressions each highlights the other’s qualities. The existing building is not simply a repository for the new, rather the new enables the reinterpretation of the original fabric, inviting one to look again and discover through material and structural layering.

It is not only the gesture of intervention that distinguishes this extension but, more critically, the approbation of the typology. This is most evident in the foyer, which is the main circulation space and allows access to each commercial floor. Here, contrast is activated both spatially and materially. Internally the space is dramatic, unfolding vertically and accentuating the impressive proportions of the warehouse envelope.

Rooftop glazing allows light to enter the void, amplifying the sense of height. The new structure, a massive steel frame that supports the roof canopy, is strutted to the warehouse wall, projecting through and above the parapet. Separation acts to contrast, with steel and brickwork detached and isolated. Materially, the multiple layering of elements and planes, both structural and non-structural, stimulates a comparative reading. Opposing expressions range from the highly refined and patterned to the massive and robust and the delicate and lean.

Woods Bagot also deploys this strategy of contrast within the intervention itself.

The main foyer stair, the centrepiece of the building, shows this well. Playing off the heavy steel frame is a stainless steel pin-and-cable system, an elegant and highly detailed assemblage that suspends the stairs from the new steel roof structure. Similar to the exchange between old and new, transparency and massiveness, the expression of tension and compression sit in close proximity. The stair is connected to each floor via a series of bridges, cantilevering mid-space and detached on all but one edge, providing the opportunity to survey the theatrical oppositions.

In contrast to the layered quality of the entry foyer the commercial floor areas have been minimally treated and offer uninterrupted open space. While this strategy avoids the reductions of conventional subdivisions, it nonetheless fails to provide the subtle spatial markers and indications of boundaries that may have assisted the furnishing and occupation of the space. Further, the independence of these areas from the central void – a likely result of fire safety regulations – denies them the material and spatial juxtapositions that underpin the appeal of the project.

The circumstances surrounding the construction of this building – an unusually committed client, disciplinary collaboration and a discriminating approach to detailing – have generated an architectural response that is neither a spectacular gesture nor a corruptive appropriation. Rather it is a resolved articulation that promotes a reading based on difference, distinction and re-interpretation. The project displays a thoughtful and rigorous approach to architectural conversion, and demonstrates the importance of collaboration and agreement between architect and client.

BELINDA BRITO IS AN ASSOCIATE LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES.

Project Credits

ULTIMO WAREHOUSE

Architect Woods Bagot—project team Robert Cahill, Domenic Alvaro, Andrew Colangelo, Greg Harper, Scott Henderson. Client Mountain Street Partnership. Main building works Kell and Rigby. Services engineer Norman Disney and Young. Structural engineer Enstruct Group.

Cost Page Kirkland Partnership. BCA Phillip Chun and Associates. Fire engineer Arup Fires. Acoustic Bassett Consulting. Geotechnical Douglas Partners. Facade assessment Hyder Consulting. Timber assessment State Forests of NSW. Heritage Godden Mackay Loggan.

Signage Claude Group. Graphic design Alison Curry.