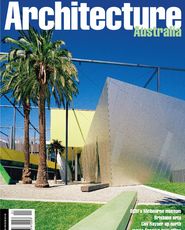

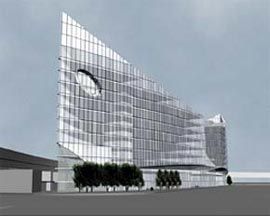

The winning entry – “TransparCity” – from John Wardle Architects and Becton. The proposal displays a dense urban program behind a glass surface. It provides a critical mass of complementary uses to invigorate the site and create a viable commercial framework to support the significant allocation of low cost accommodation.

Melbourne’s Hanover Design Competition was an unusual architecture competition.

Most competitions are driven by the wish for an important building on an important site: a new focus for civic pride. But this site is harsh – derelict land on the western edge of the city with a railway viaduct overhead and edged on the north by one of those awful road flyovers beloved of 1960s traffic engineers. The motivation for the competition was also harsh, and not a source of pride for a wealthy society – the need to fund a new program to assist the children of homeless families.

Hanover Welfare Services is a long-established agency working with Melbourne’s homeless. They approached RMIT to discuss how money might be raised for the new program in a way that would draw attention to both the built and social environments that contribute to homelessness. This design competition evolved over months and brought together key city players: Hanover, the City of Melbourne, the Victorian Government, the Age newspaper, the RAIA, major developers, and RMIT. Beyond the initial catalyst of raising money, the other objectives were to raise community awareness of the social costs incurred when accommodation is lost as older areas of the city are redeveloped, and to invent ways of incorporating some of this accommodation in new developments.

The Age’s support was central to enthusing the developers and to achieving public debate about the competition issues. For the newspaper, the competition offered an opportunity to discuss some issues around low income accommodation, and to look at how decisions are made about uses for big sites, how briefs are written, and how design responses are developed.

The fund raising was a simple – although mildly impertinent – idea. Melbourne’s eight major developers were each asked to donate (a tax deductable) $10,000 to Hanover in return for the opportunity to be paired randomly with an architectural practice in the competition. As there were no means available for the architect’s work to be tax deductable, the Victorian Government agreed to give $20,000 as first prize to the winning architectural practice and the City of Melbourne agreed to give $10,000 as the second prize. It was made clear to the competing teams that, while both the city and the state (the land owners) were interested in the site being developed in some way at some future date, no commitments were being made about the winning entry being pursued.

The site has some symbolism for a project around homelessness. It is on the corner of Flinders Street and Spencer Street, an area where, a dozen years ago, there were 20 cheap hotels which housed hundreds of people on low incomes. A decade later, these are now boutique hotels with gorgeous bars and swish bedrooms – and a different clientele. So, as the city has changed, people who earlier led humble but independent lives have been made dependent. This competition was a way of understanding those changes and investigating new ways of looking at sites and projects which could return some equity and independence to these people.

The brief required all proposals to (1) assume the demolition of the King Street flyover and to create active frontages to all four site edges, (2) consider shadow diagrams for Batman Park and the Yarra River (to the south of the rail viaduct), and (3) incorporate 12 units of accommodation to be managed by Hanover. Beyond those requirements, each consortium was able to develop the site with any uses it saw as feasible. Mark Healy, from Six Degrees, put the brief more succinctly: “Find some innovative uses for this abandoned city site and make it stack up.” John Wardle Architects and Becton won first place with “TransparCity”. Wardle once described his proposal as an “ant farm” – a dense urban program displayed behind a glass surface, providing a critical mass of complementary uses to invigorate the site and to provide a viable commercial framework to support a significant allocation of low cost accommodation. It is presented as an urban showcase that teases out and celebrates the architectural opportunities of the complex program and puts them on display behind an environmentally active glass facade. The 34 metre high glass container recalls the proportions of the Victorian Fish Market which was once on the site, and has the patterns of activity pressed against the glass.

The proposal creates a market as a “shop front” to the site, activating each of the program elements for the entire length of Flinders Street. To enter the front door of every element – the hotel, the low cost accommodation, the university, the urban supermarket, the housing, and the museum and wetlands – one has to pass through 11 metres (two stall holders) of market. One stall holder, the fish shop, is enclosed in a slender glass chamber.

The urban supermarket – a single glazed structure 65 metres long by 6 metres wide – represents a single stretched module of a suburban supermarket. The museum records the history of the settlement along the Yarra’s edge, while a three-star hotel spans both railway viaducts linking Flinders Street with the Yarra River, and is interwoven with three levels of low cost housing. Wardle suggests that the hotel development would subsidise the 27 low cost units, while the swimming pool would act as a recreational facility for the university and all other users.

Ashton Raggatt McDougall and Australand won second place. Realising that standard development ideas would not work on the site, ARM and Australand were interested in devising a proposal which would underwrite the costs of building over the rail viaducts. They state, “to not build over the viaducts would seem to once again miss an opportunity of correcting this significant city planning problem”. Using the site’s proximity to a set of facilities, including the Exhibition Centre and the Melbourne Convention Centre, this consortium sought a proposal that would work in synergistically with its neighbours. The most urgent need in the precinct is for a 5,000 seat plenary facility and to achieve this they propose a skywalk link to the Convention Centre.

So ARM and Australand’s development concept revolves around the plenary complex and its associated conference and breakout facilities, with other elements being parking, the Hanover accommodation, a hotel, some retail, and a street level art gallery and exhibition area.

The works presented show something of the dreams that architects can generate for cities, and demonstrate that developers can be part of that dreaming. While these were shotgun marriages between developers and architectural practices that had not worked together before, the jury noted that “all the schemes benefited enormously from this collaboration, both in the sophistication of result and in the moves both parties were prepared to make outside their normal comfort zones”.

Dimity Reed is professor of urban design at RMIT. RMIT and the RAIA Vic Chapter believe Ideas for the City could be replicated around Australia. Dimity would be pleased to outline the process and to discuss details. dimity.reed@rmit.edu.au

PETER ELLIOTT ARCHITECTS AND THE DOCKLANDS AUTHORITY

This proposal, above, would create a transport interchange, to serve private and public transport, in the south-west corner of the grid. The interchange provides for bus, tram, train, car, pedestrian, bicycle, water taxi, tour boat, helicopter and scooter. Support facilities are fused into the transport interchange and two levels of basement car parking provide 350 spaces.

The site is accessed from all quarters. New, mid-block laneway connectors open up the interior of the site and connect the river to the city. A thin sliver of occupied space wraps the railway viaduct and connects it with Batman Park. The viaduct – enclosed on the sides to acoustically isolate it from the new development – remains open to the sky; trains passing into the site will partly disappear and reappear, depending on the vantage point.

Floating above the viaduct level are three independent container modules, aligned north-south to allow sunlight, views and air to penetrate into the levels below. Each incorporates gardens, and public and private recreational and entertainment facilities linked across a public podium along the Flinders Street face.

A linear sky bridge is slung on top of the Flinders Street frontage, spanning the elements below. This is building as bridge – on a scale to match. It is also a counterpoint to the curving viaduct, which snakes its way around the city, acting like a giant cornice propped on legs that pierce the spaces below. Its location minimises shadows on the park to the south, and holds the Flinders Street edge. Internally, it contains four levels of serviced apartments in the centre and offices in the two end zones. Pleasure gardens in the sky activate the roofs and include swimming pools, spas, gym, tennis court, running track, playground, leisure garden, sun deck, spectator terraces, services, cafes, bars, restaurants and clubrooms.

KERSTIN THOMPSON ARCHITECTS AND GROCON

Kerstin Thompson Architects and Grocon, centre left, saw the competition as an opportunity to confront one of the Melbourne’s defining urban relationships – the question of how the city relates to the river. The objective pursued here is the idea of the site as a link between the city and the river.

The suggestion is an integrated finger-development combining narrow buildings, intimate laneways and an urban forest in lieu of a single-envelope building. Existing pedestrian routes continue down to the river while the water is moved into the city. This strategy interlocks the built fabric of the city with Batman Park and the Yarra River. Built fingers negotiate their way across the site, over and under the viaduct and around its piers. Between these fingers are strips of landscape – gum forests, canals, reflective pools and laneways.

Avoiding the superobject, the scheme explores an urban gesture for the site by creating a series of discrete elements set within a pattern of lanes and arcades. The development of the site is integrated with the park and the water, interlocking both with the built and city fabric. Low rise buildings focus on the major civic component – the transport interchange – integrating the railway landscape into the design.

What is not built is central to the design – a network of interstitial and circulation spaces provide an urban fabric designed to encourage occupation.

ELENBERG FRASER AND ABIGROUP

Elenberg Fraser and Abigroup, bottom left, pursued a strategy of civic regeneration to generate an idea of the city and to explore what that idea might look like. This strategy led them to imagine a new kind of urban complexity – one where the problems of the city are solved through integration of the social and physical elements. Each of the revitalised “programs” was compressed into a “husk”, or skin, like an urban container that clips over the viaducts – bridging the garden and the city. The stacked programs present an intriguing analysis of the components of the modern city. These were divided into eight categories: red light, retail, commercial, cultural, accommodation, transport, entertainment and garden.

The red light program holds a detox centre, injecting rooms, brothel, chemist and family planning centre. Retail includes, predictably, discount outlets, specialty stores, duty free, supermarket and basement retail. Commercial includes offices, function centre and conference centre. Cultural includes the Modern Art Museum of Australia (MaMa), artist studios, book shop, library, museum shop and cafes. The accommodation program holds commercial housing, Hanover accommodation, hotel and serviced apartments. The transport program holds the transport interchange, park and ride, short and long term parking and valet parking. The entertainment zone includes theatre, cinema, fitness centre, discotheque, bowling alley and restaurants. The garden has atrium gardens, hanging gardens, courtyard gardens and a sloped garden plate.

The building links the garden to the city. The garden is pulled through and around the structure, creating an undulating ground plane or a series of embedded gardens within the site. It is possible to walk through the building, along this garden plate, without engaging with the commercial program.

This project brings the garden back into the city.

LYONS AND MAB

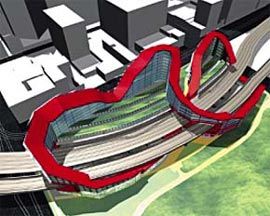

This project, above left, proposes that the railway viaducts should not be covered over, or treated as a blight, but treated more as an interesting urban event that could provide a new way of seeing and occupying this part of the city. The proposal suggests that the site should sustain a large, complex building form rather than a series of individual buildings, and that this building be used to stitch the city, Batman Park and the railway viaducts together. The project is characterised by a continuous, eight metre wide container of activity that is tied, twisted and looped around the site in a figure eight configuration. This container is stratified into four layers: retail at street level, entertainment at an upper ground level, flexible office spaces above, with the remaining levels being residential apartments ranging from one to four bedrooms and including the dozen Hanover units. These varying layers of activity are serviced by an internalised central carpark.

NATION FENDER KATSALIDIS AND MIRVAC

NFK and Mirvac, centre right, proposed “Flinders Ark” – an iconic boat-like form docked alongside the Flinders Street viaduct on the Spencer Street corner, identifying its address and creating a new aspect to the city. The single container houses a community of different urban uses (commercial and residential), revitalises the corner, and provides a fluctuating 24 hour hub of activity.

At ground level, a tree-lined internal street forms a major axis, echoing the curving geometry of the viaduct and the site, and providing the connective tissue between these two urban objects. A series of walkways cross the major axial path linking Batman Park with Flinders Street. These are lined with cafes, restaurants and retail outlets, and entries to residences and offices.

Tucked into the underside of the viaduct, a series of vaults accommodate workshops and studios or businesses that require smaller tenancies. These vaults form an edge to Batman Park and activate the parkside promenade.

SIX DEGREES AND STAGED DEVELOPMENTS AUSTRALIA

Six Degrees, right, propose recreating the site as a vibrant corner of the city, meshing private and public desires to accommodate a rich mix of users. Their idea is to create a framework which might allow history to layer the site over time – an urban park of various commercial and public components, funded predominantly by revenue generated through dedicated advertising zones – an “Advertising Heaven”.

They have moved beyond the site for the provision of the accommodation – to the north over Flinders Street where they suggest a community of mixed income shop-top houses over street level businesses.

To achieve funding for the public uses of the main site, the advertising concepts move way beyond the billboard. There is multi-dimensional imaging in and around the site, located on non-static exhibition spaces – including projections on water walls, on the train station, and on glass walling.

An additional rail station in the loop system, the new station becomes the largest building in the development and links the Yarra pedestrian bridge to the Exhibition Centre.

The Judges

Tony Nicholson (chair), CEO, Hanover Welfare Services; Alan Attwood, The Age; Vanessa Bird, Bird de la Coeur Architects; Stuart Niven, Melbourne City Council; Rod Fehring, Victorian general manager, Delfin; Jill Garner, Garner Davis Architects.