Winning entry by Jeppe Aagaard Andersen, with a team from Denmark and Perth, which proposes bringing the water to the city by flooding Dunn Place.

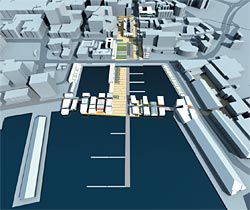

Winning entry by Hobart/Melbourne firm Preston Lane Architects, with James Whitten Architect, which proposes replicating existing urban spatial patterns across the entire competition site.

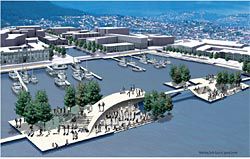

Winning entry by Tony Caro Architecture, which creates an urban plaza and bridges the windy docks with a set of north-south buildings.

After years of wading in the still waters of economic recession, there is movement in the southern ocean as a tsunami of development brews. Riding high on the wave of a booming real estate economy, Tasmania has one hand on its collective boogie board, watching the swell, slightly wary of the potential investor-sharks lurking beneath the surface. All eyes are focused on Hobart’s Sullivans Cove, one of the earliest sites of European settlement, and home to the largest collection of the oldest buildings in Australia. Along the east and west edges of the harbour the arty types have bunkered in, establishing places of fertile creative life in the crevices of the abandoned industrial buildings, which have become the catalyst for Hobart’s cultural identity. Lying dormant in the centre of the cove, two blocks from the city centre, are the remnants of the old working port, which harbours a small fleet of fishing boats and yachts, surrounded by a vast windy tarmac. This is seasonally invigorated by summer boating carnivals and festivals, but is constantly buffeted by chilly southerly winds, and mostly used as a car park. This tremendous broad flat site with an amazing view is a place full of history – and ripe for development.

So Hobart invited the world to speculate on the future of this extraordinary site through an international urban design ideas competition. Offering a healthy bounty of prize money and significant professional kudos provided by an esteemed jury of Carme Pinós, Wiel Arets, Geoffrey London and Catherin Bull, the competition attracted 280 entries from 51 countries, outstripping the response to previous architectural competitions in Australia. Results were announced in late January and an exhibition of 28 selected schemes was held at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery over the following three weeks. Local Hobart-and-Melbourne-based practice Preston Lane Architects, with James Whitten Architect; Sydney firm Tony Caro Architecture; and Jeppe Aagaard Andersen (with an international team from Western Australia and Denmark) were each awarded equal first prizes of $50,000. Four entries from universities in Australia, Slovenia, France and Italy shared the $10,000 student prize.

The competition was restricted to a finite zone within Sullivans Cove, a somewhat arbitrary envelope, described as the City Hall Axis. This zone contains the old City Hall, at present barely used, and a collection of other vacant but historically significant sites. The brief called for schemes to provide urban ideas for the precinct and, in particular, create a stronger connection between the city centre and the waterfront. Despite the proximity of the city to the water, this relationship is currently undermined by the couplet of four-lanewide, one-way streets that run east-west across the cove. The sites surrounding City Hall were seen as a key stepping stone between the two places.

The term “City Hall Axis” originates from the current Urban Design Framework for Sullivans Cove, which is arguably overly preoccupied with a traditional planning grid. This tacitly implies that the line of the grid might continue from the land into the harbour, culminating in a new pier. Unfortunately, the majority of the schemes seemed to have hooked the red herring and focused on this approach, creating new linear piers adorned with iconic buildings. Without a more detailed reading of the existing urban patterns and natural topography, this approach resulted in seemingly random invention of both programme and form, a kind of architectural “wish list” unrelated to the constraints and opportunities of the site. Fortunately the jury could see past this obvious gesture. Concerned that the majority of the schemes were “too loud”, they were interested in proposals that engaged with more subtle particularities of the place. The jury established ten guiding principles that they considered should be fundamental to development in the cove, and assessed the schemes on this basis. They emphasized the importance of scale, preferring an approach they described as “many minor moves”.

The three winning schemes all resisted the pull of the axis, using other tactics in an effort to “draw the city to the water”. Andersen’s team inverted this idea by proposing to “bring the water to the city”, flooding Dunn Place and making City Hall an aquarium. The existing docks were joined together to form a “bay” and the link across the cove was reconfigured as a (curiously scaled) “island”. Team Caro created an urban plaza extending from City Hall to the harbour, but also focused on the link across the cove. Their scheme endeavoured to bridge the width of the windy docks with a set of buildings oriented north-south that provided mixed use and created a more controlled microclimate within the cove, while allowing views to the water. Preston Lane were obviously able to trawl over the site in great detail and identified a set of current urban spatial patterns, which they proposed could be replicated throughout the competition site. Their scheme prioritized the ideal of creating urban space rather than architectural form.

The competition was intended to generate ideas, rather than to determine a finite proposal for the cove – this will not become a real urban design commission. This doubtless influenced the demographic of the entrants and it is interesting to note the absence of “big name” architectural practices, despite the number and scope of the entries. The value of an ideas competition is that it produces a great selection of visualizations that represent a gamut of ideas. These can become the catalyst for discussion to assist in developing a definite brief and clarifying priorities.

Wandering around the exhibition and eaves dropping on the locals, it was fascinating to witness the intensity with which many people studied and discussed the ideas on display. While many of the comments related to the practicalities of circulation and use (revealing that most of the designers have no idea how to “park” a boat), it was encouraging to hear the reactions to the myriad ideas, which demonstrated a willingness to engage positively, yet critically with the ideas presented. “Wow, fancy that … there’s an ice rink in the middle there”, “well, it’s just a fish and chip shop, I suppose it’s possible to move it somewhere else”, “no, that’s no good … It’s all old buildings around the edges, and this looks like something out of the Jetsons.”

Beyond the hype of the international competition, it is important to recognize the two sets of interests at play: culture and economics. Tasmania is in a difficult position – it has a potentially burgeoning economy, but not the critical mass of people to sustain major-scale development. While there is doubtless a genuine acknowledgment of the cultural and social significance of this site, the competition arises from a need to establish a new statutory framework for the cove in order to facilitate development. The Waterfront Authority has appointed a Design Panel to assist in this process, but their role is limited to providing “expert advice and discussion” on the waterfront, rather than a more central role in the development of urban design policy.

One of the dangers of ideas competitions is the temptation to pick and choose various discrete ideas without a clear relationship to a cohesive overall agenda. There is a risk that the government, in their haste to encourage investment, may be too eager to find an expedient way to slice up the land, prioritizing short-term piecemeal development over long-term strategy, which may be more complex to implement. It is essential that the sea of ideas presented in the competition is not used to justify this process. Clear urban design intentions that acknowledge the cultural, social and historical dimensions of the site should underpin the legislation needed for future development, and this will require the current Urban Design Framework to be broadened in both scope and aspiration. I hope this is just the first competition in a comprehensive process of urban design development.

Pinós and Arets highlighted the need to consider principles for the city, including for the entire cove, from the edge of Battery Point across to the Domain to the east, not just the narrow zone of the competition site. They suggested various themes that should be addressed: tourism vs living; relationship to the water; and allowing building fabric to change with the changing patterns of use in the cove. Arets observed that one of the inherent characteristics of the working port is the pattern of flux, and suggested that the utilitarian nature of the working port allowed a robust attitude towards the existing fabric. To the chagrin of many locals, he suggested that there was a need to “clean up” the cove, to perhaps demolish some buildings in order to change the character of the place from a working port to an “urban plaza”.

The next step in determining the future of the cove is crucial. The intention is to analyse and collate the range of ideas presented in the competition in order to establish some guiding principles for development, but the specifics of how this process will proceed are not clear. In the absence of a government architect, the Sullivans Cove Waterfront Authority Design Panel is pivotal to this process, and their role may need to be expanded to allow for their participation at a level that would allow effective engagement. It is essential that the profession and the public continue to engage with this process to ensure that the competition is not used as a smokescreen to veil an underlying political agenda.

Helen Norrie is a lecturer in architecture at the University of Tasmania. All entries to the competition can be seen at www.hwidc.tas.gov.au

Jury guiding principles

[01] Scale: many minor moves

[02] The public realm

[03] Activation

[04] Accessibility/connectivity

[05] A rich experience

[06] A humanized (and healthy) environment

[07] Distinctive and authentic

[08] Change for the better

[09] Design well

[10] Think for the future