<b>REVIEW</b> GRAHAM CRIST <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> TREVOR MEIN

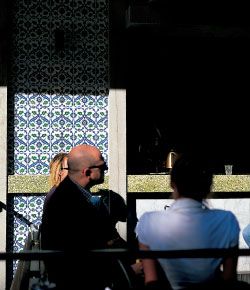

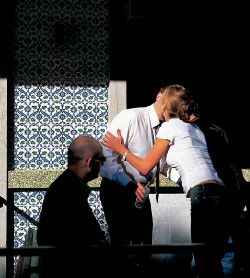

Interior details.

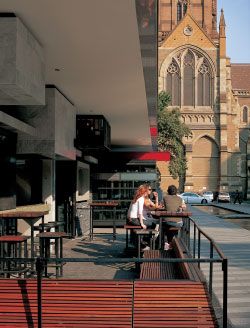

Looking along the length of the new tenancies at the base of the Westin Hotel, with St Paul’s Cathedral beyond.

Views along the City Square facade, at the base of the hotel, including the roll-out seating bay and yellow kiosk doors/walls in various configurations

The 3 Below bar spilling out into the square.

Interior view of the roll-out seating bay in the cafe.

The permeable edges enliven the square.

A witty response to the Westin Hotel above, the corridor running along the back of the bar is reminiscent of a luxury hotel corridor without the suites.

The warm, rich interior of 3 Below bar.

Overview of the cafe, looking towards the kitchen.

Detail of the cafe.

SOME TIME AFTER the completion of the Melbourne Westin Hotel, a series of tenancies have been completed for the space on its ground floor facing the City Square. At its north end is a Starbucks, and next to this is a series of shopfronts designed by Six Degrees. These include a bar (3 Below), a cafe and two hole-in-the-wall kiosks. They form an intriguing edge to the plaza and a base to the hotel towering over them.

A key issue for this project is context – more specifically, how a design might respond to or be affected by its context. This question is critical in this particular problematic context, and for an office whose work generally involves a close examination (and acceptance) of the surrounding built environment, as found.

Six Degrees is known for a series of projects that re-use and recycle building materials and finishes from other places. This reputation began with the Meyers Place bar, which spawned many other bar and cafes, including Phoenix in Flinders Street and The Wall in East St Kilda. A number of residential projects also share the same traits of relying heavily on found materials and the remains of the existing building for their primary effect. The projects were at times pigeonholed as cheap tricks with cheap materials and left at that. However, other projects such as the alterations to the Kooyong Lawn Tennis Club, which cleaned up the planning and circulation but didn’t really clean up the aesthetic, suggested that there is a broader agenda at work.

Six Degrees’ architecture is not just about recycling. Indeed, the architects find it frustrating to be constantly cast as architecture’s bowerbirds. Firstly, the material choices are about texture – the surface effects that can only be gotten from old, worn things. There is a search for lushness, as well as a reaction to newness or to architecture’s tendency to clean things up and bleach them white. Secondly, there is an engagement with a built context in a very literal sense. Context either displaced, or left, while the design is roughly stitched around it. The relation to an existing context is very direct and often all-encompassing, subsuming the architecture. It reflects not only an acceptance of the built environment, but an affinity with it, with dirty realities. Such projects want to be part of the back lanes of Melbourne, not just reference them.

These strategies result in a kind of anonymity, a silencing of the works against the noise of the city. They tend to be less obvious, at times almost invisible incursions. One signal of this is the blank signage that fronts some of the projects. So an empty, glowing yellow box – a sign without words – hangs over Phoenix. Anonymity resists the architectural tendency to remake the city anew, to “correct” buildings and to recast them in the architect’s own image. These strategies are anti-utopian; just one narrative amongst a whole lot of others. They are most successful when they are least predictable.

So what happens when the architects move out of the back streets? City Square, which forms the ground for this project, has its own chequered history – exemplified by Ron Robertson-Swann’s sculpture Vault. Its removal from the square in 1980, only a few months after installation, marked the beginning of the view that the square was not successful, despite being the outcome of Denton Corker Marshall’s winning competition entry of 1976. The construction of Federation Square completed this view, and in 2002 City Square was reworked and partially replaced by the hotel. The sculpture, which had become colloquially known as the Yellow Peril, was moved a couple of times and finally located near the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Southbank.

As a context, the Westin Hotel presents problems for the Six Degrees project. It massively out-scales the tenancies that huddle under it. The hotel, in fact, is tall and bulky next to St Paul’s cathedral and curiously did not attract the same contextual anxiety as Federation Square’s ill-fated western shard. The Westin’s language is a mixture of mock-historical (pseudo-French) and corporate moderne – slick beige and tasteful zinc. Its front onto the square is more a side, since this facade conceals the porte-cochere/drive-through entry accessed from Collins Street and Flinders Lane. This tends to preserve City Square as its own space, rather than it simply becoming a forecourt to the hotel, but it leaves the new tenancies exposed on the eastern edge of a fairly open plain.

In contrast with the formality of the Westin entries, the new work provides a very activated facade. These are, of course, the kind of urban design values appreciated by planners. The multiple entries face straight onto the plaza in a relatively informal way. The bar spills out directly onto the paving and serves across its facade, much like Meyers Place. The small kiosks are door/walls that hinge and flip open. When they are closed they are bright yellow memories, flattened fragments of Robertson-Swann’s Vault. The cafe has a whole section of facade and floor that rolls out onto the square, and a projecting girder over pretends to support its weight. The “activity” of the facade is rhetorical, excessive. Perhaps it needs to be to counter the breadth of the square and the weight of the facade over it.

The architects might have found it difficult to respond to the style of the building above them, given their taste for modernism on one hand and rich texture on the other. They have reacted primarily through contrast. The mood is dark, rich and highly varied in its materiality. The scale is tiny and intimate. It is everything the hotel is not, and ironically, the effect is like a traditional European bar or bistro, dark and woody. There are conscious references to the robust interiors of generic cafes – perhaps Pellegrini’s, perhaps French railway cafes. It makes a witty comparison to the more pompous flavours of the Westin. Most amusing is the little corridor running across the back of the bar and connecting the kitchen, cafe and toilets. Dimly lit, mirrored, with carpeted walls, it speaks of the sumptuous hotel corridor. It is the luxury corridor without the suites.

These qualities assert the depth of the interior – the quality of having an interior. This is not to be taken for granted in a thin strip of space at the edge of a starkly open space where it could be taken for a verandah. The spaces instead have substantial depth and enclosure.

One issue does arise, however. Despite the discussion of unpredictability and immersion in context, a repeated stylistic tendency still surfaces in this and other works by the practice, something between de Stijland Art Nouveau. Perhaps all architects have a fallback position, but they are most interesting when they have most to grapple with, or respond to, in order to disrupt this.

Six Degrees have asserted the interior nature of the city for some time – small spaces and dark spaces, the familiarity of the long known. It is a quality exemplified by the exhaustively celebrated lanes. Asserting such qualities here, at the edge of an open field, is startling. It provides a moment of intensity and offers strategies that could be taken into much larger projects. This is an acute case of the disjunction in our cities between the street life and the infrastructure overhead, just as Melbourne’s best lanes sit amongst its corporate towers. Fortunately, we can now sit under the Westin and look out at the City Square, just as Guy de Maupassant would lunch inside the Eiffel Tower. Here we can enjoy the architecture and think about the contemporary city.

GRAHAM CRIST IS AN ARCHITECT AND A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT RMIT UNIVERSITY. THANK YOU TO FRANK PTY LTD FOR HELPING WITH PHOTOGRAPHY.