<b>REVIEW</b> Paul Walker

<b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> Trevor Mein

Detail of the brick snaps used on the facade of the multipurpose hall.

The “agora”, or atrium, a vibrant public space.

The atrium is penetrated by an opening to the sky and one to the lower level, allowing light to reach both levels.

Looking towards the timber battens of the northern teaching building, with a landscaped area in the foreground.

Looking along the facade of the main teaching building, with the atrium in the distance.

Interior of the lecture theatre.

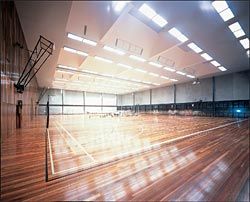

Interior of the multipurpose hall.

Looking from the end of the large connecting walkway towards the amenities and lecture theatre buildings.

Exterior of the multipurpose hall.

Deakin Central consists of four buildings and a spare roof. Described by programme, the buildings are: a lofty recreation hall that can be used for a number of court sports, and for university examinations and other activities; a three-storey block for administration and teaching spaces; an amenities building with a bank and various food-and-beverage outlets and a new meeting room for the Deakin University council; and a large lecture theatre.

Between the four is a sheltered public space the architects call an “agora”. Together these spaces refocus a growing suburban university campus, and suggest ways to think about both its past and its future, practically and speculatively.

Deakin Central, in some ways, corresponds to an earlier project, also on Deakin University’s Burwood campus. This is also a group of four buildings, designed by Wood Marsh, with Pels Innes Neils Kosloff, and completed in 1997. Arrayed not around a shared public space but around a central stair tower, it includes a slab that, located near the Burwood Highway side of the site, has become an important architectural billboard. Its two long, curving masonry walls – eight or so storeys – with off-set punched-out windows are immediately recognizable. Here the university has used architecture to stamp its ambitions on what had previously been a modest teachers college.

Located at the other end of the campus, and breaking out of its previous development footprint, Deakin Central is focused on promoting the university’s internal culture rather than making an iconic image for external consumption. This can be seen as the next logical step in the evolution of the place and of the institution. Rather than addressing the adjoining public condition – that of a suburban highway – it asserts an ideal of what the university’s own public realm should become. Such an intention is signalled in the use of the term “agora”. This is a loose-fit space, with a variety of activities spilling into it – the hourly flow in and out of lecture theatre and seminar rooms; movement from sports activities; people mooching in cafes, or circulating to and from an adjacent car park structure; supplicants coming and going from campus advisory services.

The agora is at a datum level already established by a key element of existing infrastructure, an elevated pedestrian way which cuts diagonally through the campus. This also determines the principal floor level for each of the four Deakin Central buildings. Under the agora is vehicle access across the site, and a bus drop-off and pick-up point that potentially can bring public transportation to the middle of the campus. The agora is ruggedly built of concrete, with some brick pavers inlaid.

Stairs and a lift connect it to ground level, as does a low-pitched ramp via a long route between lecture theatre and amenities buildings, zigzagging down at the western end to connect with a path that crosses the adjacent creek. The elevated pedestrian structure will ultimately follow this path over Gardiners Creek to another area Deakin is developing to its west, exposed to another major arterial road. Here are more new academic buildings, also by H2o, currently being constructed for the university. While pursuing a formal language and planning strategies of their own, these buildings on Elgar Road feature brick-lined interior light courts that acknowledge both the suburban context and their architectural colleagues across the creek. The development of this further precinct will shift the campus’s centre of gravity so as to justify the claim of geographic focus entailed in Deakin Central’s name and suggested in the public space it creates.

Instead of producing objects to be seen in the round, the architectural approach at Deakin Central has led to a group of buildings that individually may only ever be viewed as vignettes from the agora or the various pedestrian and vehicle routes through and alongside the complex. The new buildings each take their repertoire of forms and materials from a common but reasonably wide language. Bricks and timber are important to this: they are code for a kind of naturalness to which the whole ensemble alludes.

Brown bread and butter, but the bread has plenty of raisins. In a sense, Gardiners Creek – currently a boundary between the Burwood site and the Elgar Road one – will in the future be a green space at the heart of an expanded and integrated single campus.

All this lends logic to the material and formal palette. The buildings are mindful of the campus’s future, not only in terms of their own place at its social and material centre, but also by being built to be flexible – carefully calibrated in environmental performance, but restrained in technique. H2o have used an 8.4-metre grid in the teaching building, for example, which they find accommodates various configurations for seminar rooms and academic offices. Screens in front of northern and western openings offer modest degrees of operability. The main structural floor of the lecture theatre is flat so the building could readily become something else.

And so on – such gestures to potential futures are everywhere in these buildings.

Deakin Central is also concerned with linking itself to an ecologically defined past. Brick snaps in multiple colours are disposed in bands – horizontal or angled – across the concrete panels of the sports hall walls and on external walls of the teaching block. The timber is also mostly horizontal but is sometimes used diagonally. Boards are butted to make a surface over the volume of the lecture theatre, spaced to make screens elsewhere. The angles in cladding materials are repeated in occasional plan inflections in the envelopes of the recreation hall and the teaching block.

For the architects these things have a geomorphic rationale – the plan zigzags, and bands of coloured bricks are akin to geological strata or layers of flood-deposited sediment. Apparently once used as a rubbish tip, the site presumably used to have more topographical shape than is apparent now. H2o allude to it as a displaced landscape.

This rationale does perhaps not much matter to a building user or visitor – the details in the cladding treatment that follow on from the geological-cumlandscape metaphor, or the occasional skews in plan, will be apparent to them as a secondary conditioning of the building. Graphically effective from a distance, the bricks have a homey quality close at hand: Burwood, after all, is a brick-and-tile suburb. But they are also made out of the ground to which the design keeps alluding. Even the relationship with the creek and its adjacent landscape of trees and grass is conditioned in this way to play with scale. Screens and frames to the balconies that give access to the rooms in the teaching building, or over the glazing to various north- and west-oriented spaces in the amenities building, disaggregate the views and make them more intimate.

And that extra roof? It both covers the agora and – through an array of skylights – illuminates it. Its receding and projecting planes are also the impress of a lost terrain. But painted white and yellow, it feels both literally and metaphorically less weighty than the rest – a lemony meringue instead of a wholesome loaf, a cloudscape instead of a landform, dream-like rather than chthonic. It’s a strangely beautiful thing.

DR PAUL WALKER IS ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.

DEAKIN UNIVERSITY CENTRAL PRECINCT, BURWOOD, MELBOURNE

Architect H2o architects—project team Tim Hurburgh, Mark O’Dwyer, Jim Tsoukatos, Alison Binks, Cameron Clifford, Peter Badger, Karl Singline, Sofia Anapliotis, Adrian Stelmach, Catherine Marks, Chris Price, Ngia Phan, James Tinsley, Sam Penfold, Joseph Nichols, Jacque Bennett, Imogen Pullar, Louise Knapp. Interior design H2o architects. Design and construction manager Deakin University Project Design and Construction Management, Wycombe Constructions. Quantity surveyor Wilde and Woollard. Building surveyor PLP Building Surveyors and Consultants. Structural and fire engineer Meinhardt. Civil engineer GRA/ Rimmington and Associates. Landscape architect Rush Wright and Associates. Services engineer AHW Consulting Engineers (Vic). Acoustic design Marshall Day Acoustics.

Client Deakin University Property Services Division.