Photography by Trevor Mein. Comment by Anthony Styant-Browne.

There are two remarkable things about Lyons’ second stage building for the Box Hill Institute of TAFE’s Nelson campus. They are its skin and its partial sphere. Built on the site of the old Holeproof factory on Whitehorse Road, this two-storey stage of 5000 sq m in floor area joins two utilitarian existing buildings with a new building, and connects seamlessly to the Perrott Lyon Mathieson first stage completed in 1995. Integration of the disparate buildings and two construction stages was a stated objective of both architect and client, and this has been effectively achieved through three strategies. First, through organisation of the program, where student facilities and services are immediately adjacent to Stage 1, establishing a central locus of student activity between it and a complex of teaching spaces, workshops, computer laboratories and staff offices for Electrical Technology and the Centre for Information Technologies beyond. Secondly, through a two-level circulation route on the face of the building, extending from the Stage 1 main entrance across the west end of the forecourt, around the partial sphere to the large workshop. Thirdly, through wrapping the entire complex in an apparently single articulated membrane.

Up until the late sixties and early seventies, modernism prescribed that the exterior of a building should express both its structure and function, a prescription that gave rise to the highly plastic and deeply articulated facades of Paul Rudolph, for example. It was Cesar Pelli, amongst others, who stood this convention on its head and, following his work with Saarinen on the Bell Telephone Laboratories, began in Los Angeles to explore an opposing idea of an undifferentiated thin membrane wrapping the building, using the analogy of human skin covering and concealing a complex assemblage of bones, organs and flesh. One of the most startling of these skin buildings is the first stage of the Pacific Design Centre – the “blue whale” – a great bulging behemoth in West Hollywood, wrapped in a gasket-glazed, reverse-mullion curtain wall system of bronze vision glass and cobalt blue spandrel glass.

At Box Hill, Lyons have done the same thing with humbler materials. Theirs is a skillful and arresting composition of pragmatically arranged glazed and louvred openings in a two-toned skin of ironbark (dark brown) and off-white Easy Clad profiled metal cladding. Areas of ironbark are used as supergraphics against the off-white, here as bands wrapping diagonally across the facade, there as shadows thrown by one part of the building against another. Scattered over the skin in places are small circular roof lights which animate the surface on the exterior and are point light sources on the interior. The facade facing the forecourt is clad in a warmer wheat colour to mark the public nature of this space. Although visually successful, the configuration of the dark supergraphics on the facade may have given the building an added intellectual richness and urban grounding had they referred to some larger order outside the site. Like the floor plans of the Ecole des Beaux Arts or that of Le Corbusier’s Assembly Building at Chandigarh, the spatial structure of this building is characterised by a field of orthogonal spaces into which a single figural space is set, marking its importance. In this case, the insert is a fragment of two nested spheres. The inner, termed “the igloo” by the building’s occupants, encloses a 110-seat lecture theatre. Between the inner and outer spheres is an annular foyer of double height, and outside the outer sphere is a first floor circulation space with strip windows overlooking the annular void. While the full sphere is implied, only a fragment is constructed; the whole being cut by the planes of the bounding building, producing some extraordinary intersections. This is an inspired set piece!

It comes very close in its spatial and metaphorical presence to an architectural expression of Jorge Luis Borges’ allegorical Aleph, in which the entire universe is apprehended at an instant. There is, in fact, one point at the first floor level in which the entire building is understood at a single glance, both interior and exterior. The two orders of the building are experienced in the lecture theatre at the intersection of the spherical and orthogonal geometries

The spatial experience is reinforced by the use of materials – the underside of the sphere a smooth shell and the underside of the inclined roof plane and wall faced with a textured acoustic treatment. In the interstitial space, the foyer, the spherical geometry is cut at the roof and floor. The ceiling is a translucent gridded plane – acrylic panels under Ampelite corrugated roofing – and the floor is a lightly two-toned banded sheet vinyl; both surfaces implying the suspended nature of the sphere. The spherical surfaces are clad in MDF shingles, convex opposed to concave, coloured green, brown and blue, representing a pixilated planet Earth as seen from a satellite. The presence of the foyer is marked on the external skin with an arc of Ampelite traced on the sloped roof and wall planes.

Experientially the space is marvellous. But there are other readings. Clearly the fragment refers to the larger whole and, in apprehending the fragment, the occupant automatically constructs the whole. In this way the building’s occupants are invited to participate in its design and to reflect on the larger world outside the Institute and indeed the city. And so the building itself begins to instruct and inform, a function which has largely been lost in contemporary institutional design. Further, the architects have not made the foyer a centralised, figural space. Instead it is interstitial; a path rather than a place in Christian Norberg-Schultz’s terms; provisional. As a reflection of the contemporary condition this is more appropriate. Allocating the lecture theatre to this ‘core’ of the building makes a point about the fundamental educational form which Louis Kahn described as a teacher talking with a group of students under a tree. Here the exchange between students and teachers is given primary importance in the building’s spatial hierarchy.

Smaller passages in the building similarly delight the observer. A freeway guard rail to a loading ramp could refer to the moving steel artery of the nearby Maroondah Highway. A chevron motif on the ceiling of the coffee shop and lounge reflected in a mirrored finish to the interstitial first floor space blurs and extends the perceptual boundaries of those rooms. Built-in seating throughout circulation areas fills a functional need and provides signs of inhabitation when those spaces are not populated. An elegantly detailed continuous band of glazing lines the inner wall of the circulation path, unifying the space – at times storefront, at times display window. Skewering at acute angles through walls and floors, Atlite Tubelites cause the observer to pause, startled, like a rabbit caught in a car’s headlights.

The building also instructs in another way. Contemporary institutional design is carried out in a climate of economic rationalism, where the poetic is given short shrift, efficiency is king and budgets are low. If architects are to make buildings of cultural value they need to be clever about it. Architectural control of these building programs is limited, so it is necessary to choose carefully which parts of the building are to be high in architectural energy and which are to be low.

To my mind, Lyons have been exceptionally canny in focusing high architectural attention on the building’s skin, public circulation, lecture theatre and student recreational spaces, and allowing the rest of the building to “be what it wants to be” – although many of the spaces are a little too bereft of attention and could have benefited from some low budget tuning.

Notwithstanding that, Lyons have produced a building of unusually high cultural value within the usual tight constraints of time and budget and, furthermore, have delighted its occupants.

Anthony Styant-Browne is an architect and urban designer practising in Melbourne

Box Hill Institute Nelson Campus,

Stage 2, Box Hill, Victoria

Architect Lyons – project

team Neil Appleton, Nigel Bertram, Chris Downing, Emma Jackson, Cameron Lyon,

Carey Lyon, Corbett Lyon. Developer Box Hill Institute.

Structural and Building Services Engneers Scott Wilson Irwin Johnson.

Cost Consultants Wilde & Woollard. Landscape Architects

Paterson + Pettus. Certifers Philip Chun & Associates.

Builder Behmer & Wright.

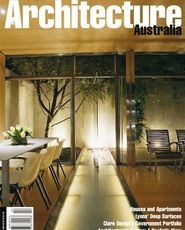

Above Ground floor corridor linking the new facilities to a factory refurbished for the Institute in 1996 by Perrott Lyon Mathieson, with café/student lounge at left. Below right Entrance to the Stage 2 building from Nelson Road, seen across the campus forecourt. Below left Smooth plasterboard wall inside the lecture theatre, with stools for latecomers.