Photos: Robert Frith

John Hejduk was once asked to comment ›› on the architectural scene in New York.

Looking at downtown Manhattan through his ›› office window, Hejduk said, “There is no life ›› in buildings.” The life of a building is a ›› judgement of the building for soul: that is, ›› of architecture.

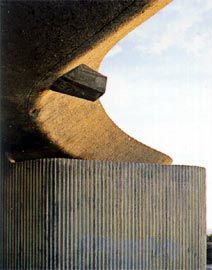

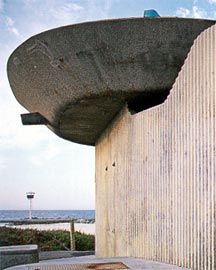

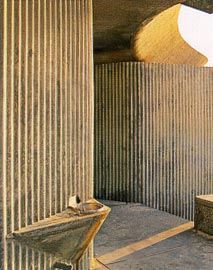

Judged by a series of building criteria, ›› those beach kiosks along Perth’s Indian ›› Ocean – designed by Forbes and ›› Fitzhardinge and built in 1970 – face an ›› “identity crisis”. Their use – they happen to ›› be ice cream kiosks and change rooms – ›› would be criticised as having inadequate ›› food preparation facilities and for sand ›› invading the buildings; their heritage value ›› would be questioned by a conservationist, ›› as the buildings are only thirty years old; the ›› buildings’ bare concrete images would be ›› “aesthetically” reacted to according to public ›› likes and dislikes; the need for constant ›› maintenance, due to the salty moisture ›› corroding the concrete, would worry an ›› accountant-minded city councillor…. This ›› list could go on. In fact, as I am writing this ›› first “Radar Delight”, one of the kiosks has ›› already been demolished, another is ›› currently being “softened” by creamy ›› renderings, and the fate of the third ›› is uncertain.

Their real values, however, are beyond ›› reason – these buildings are free spirits ›› embodied in concrete. These exaggerated ›› imitations of shells and sand waves create ›› a sense of alienness; they have given a ›› mysterious life to their place; their strange ›› dark shadows against the endless white ›› sands form a Giorgio De Chirico painting in ›› the southern hemisphere; even the ›› constant maintenance of the concrete ›› corrosion, could be seen – as Roland ›› Barthes might have – as a tragic and yet ›› poetic fight between the substantial and ›› the liquid….

But before I succumb to more frivolous ›› imaginings, we should perhaps ask if the ›› metaphor of the pavilion in the garden is ›› relevant here. A garden is our model of ›› paradise, an imitation of our imagination.

But paradise, the “Eden”, as Joseph ›› Rykwert reminds us, “was no forest ›› growing wild…. This garden the Creator had ›› Himself planted with ‘every tree that is ›› pleasant to the sight and good for food’”.

If we choose a metaphor only for its ›› affinities, then that of the pavilion in the ›› garden is both pleasurable and useful.

The Perth beach kiosks are, we might say, ›› pavilions in paradise.

The beach pavilions, like any other ›› buildings, inevitably share “double ›› identities”; they are both objects of use and ›› praxis, and vessels of spirit and meaning.

Instead of assessing only their use, ›› perhaps we should try to lift our spirit to ›› enjoy their mysterious wonder in paradise.

The primitive hut for Adam in paradise, ›› Rykwert concludes in the end of his ›› searching, is “not as a shelter against the ›› weather, but as a volume which he could ›› interpret in terms of his own body and ›› which yet was an exposition of the ›› paradisal plan, and therefore established ›› him at the centre of it”. Whether these ›› beach pavilions are demolished or not, the ›› free spirits searching for complacency in ›› paradise will have to be housed.

Dr Xing Ruan is a senior lecturer in

architecture at Curtin University of

Technology in Perth