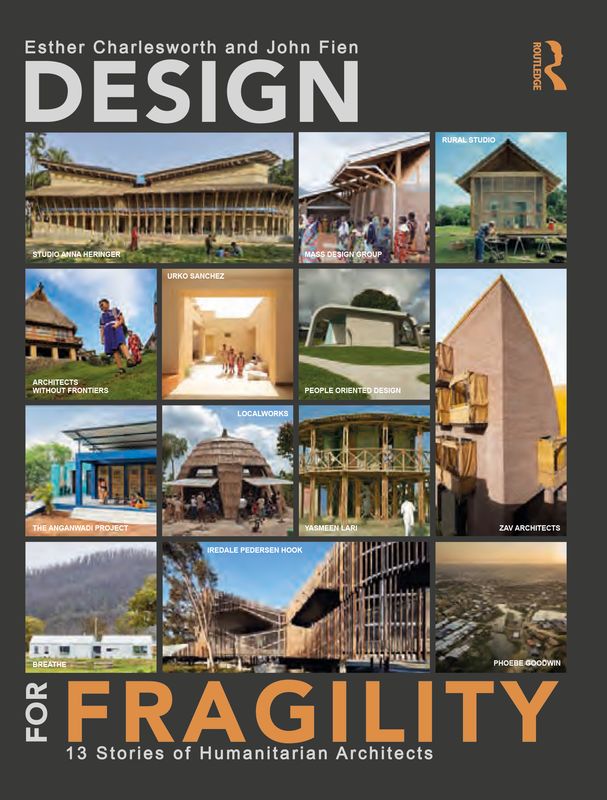

Climate change. Fire. Flood. Earthquakes. Inequality. Political instability. Conflict. What is the role of architects in this ever-changing world? Design for Fragility: 13 Stories of Humanitarian Architects, edited by Esther Charlesworth and John Fien, interviews architects who use design, new models of practice and innovative education programs to develop resilience in the face of global challenges.

Designing for Fragility by by Esther Charlesworth and John Fien (eds), published by Routledge, 2022.

Image: Routledge

Following Charlesworth’s Humanitarian Architecture: 15 Stories of Architects Working After Disaster (Routledge, 2014), Design for Fragility (Routledge, 2022) broadens the definition of humanitarian architecture to acknowledge that we are all experiencing – and must respond to – the impacts of global crises and climate emergency, albeit in different ways.

Stories of 13 projects speak to the concept of “fragile state,” in which countries experience increasing exposure to risks without the capacity to manage or mitigate those risks. Interviews with the architects about the fragilities their project had to address reveal the amorphous and interconnected political, social and environmental systems within which we all operate.

In response to such complex and varied challenges, beauty might not be the first thing that comes to mind. And yet, we know that spatial volumes and aesthetics can evoke much cultural, psychological and spiritual meaning. In places where people have survived disaster, been orphaned by conflict, fled for their lives, lived with systemic poverty, or faced ongoing discrimination, beauty takes on even greater significance.

Cobargo Santa Project by Breathe.

Image: Joanne Ly

Beauty is an expression of love and care, a sign of dignity, and an essential need in Anna Heringer’s story from Bangladesh. It is about creating moments of joy to ensure that buildings last, as Jeremy McLeod and Madeline Sewall (Breathe) explored while working with families affected by the Black Saturday fires in Cobargo, New South Wales. For Michael Murphy (part of the MASS Design Group team that designed the Maternity Waiting Village in Malawi), beauty is justice. “Architecture is always a process; it’s always social, always political. To talk about it as beauty, as an object, is to fail to articulate what beauty actually is,” he comments (page 49).

Despite an understanding that the practice of architecture cannot be separated from its sociopolitical context, it is difficult not to notice that only five of the 21 architects featured in the book are not white or Western-educated, while 11 of the 13 projects serve non-white and Indigenous communities. This reflection hits home for me, a white architect from Australia who worked in India alongside Niini Soisalo de Mendonça and local architects Harshil Parek and Shailaja Patel in 2016 to design and oversee construction of Bholu 15, a preschool built in the Ramapir No Tekro slum as part of The Anganwadi Project (TAP). TAP’s Bholu 16 preschool is featured in Design for Fragility .

When power imbalances are left unattended, international aid can result in handout cultures. Yasmeen Lari (architect for the Green Shelter Project in Pakistan) has observed locals transformed into beggars to meet their needs. “If you treat people like victims, then your attitude is very different. You believe that you are there to give poor people something, and feel good about it, rather than building up their own capacities by treating them as partners,” she says (page 112).

Bilya Koort Boodja Centre for Nyoongar Culture and Environmental Knowledge by Iredale Pedersen Hook Architects.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The power differentials inherent in their work are clearly top of mind for the architects in this book. They know that their desire to help can, in fact, be harmful. For Finn Pedersen (part of the Iredale Pedersen Hook team that worked on the Bilya Koort Boodja Centre for Nyoongar Culture and Environmental Knowledge in regional Western Australia), developing and earning trusting relationships is a critical step in mitigating this. “We must provide our services without inflaming things or doing any further harm, so we really look at community leadership,” he says (page 170).

To ensure a proactive diversification of student intake and an environment within which more feel welcome, safe and able to thrive, schools of architecture need to undertake radical self-reflection and adjustment. In addition, new models of education are needed to teach skills that support collaboration, negotiation, social impact and systemic change; and to ensure that students are equipped to meet increasing challenges. The architects’ stories in Design for Fragility remind us that there are a multitude of career pathways available, and they should all be celebrated.

Design for Fragility seeks to navigate the complexities of power dynamics, and of work in fragile contexts, by understanding the demonstrable project impacts for communities. In a welcome and important contribution to how the profession might discuss and evaluate architectural processes and outcomes with less bias and more accuracy, it includes voices beyond those of architects alone. However, the anecdotal evidence of project impacts highlights the critical need for systematic evaluations of design outcomes to give us accessible evidence of what has worked (or not) in the past – and show us what we need to change to do better in the future.

The stories contained here demonstrate both the possibilities and limitations of architectural creativity, beauty and project partnership. They offer a path forward for individuals and the profession as we try to understand our role and responsibilities in this fragile world. They remind us that there is work to be done, no matter where, how or what we are working on. These stories offer an invitation to create our own.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 16 Nov 2023

Words:

Kali Marnane

Images:

Iwan Baan,

Joanne Ly,

Kurt Hoerbst,

Peter Bennetts,

Routledge,

The Anganwadi Project

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2023