Emerging digital economies such as the sharing economy have flourished in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC). These digital platforms are changing the way we use, understand and access space and are reorganizing the city. One disrupter, home-sharing platform Airbnb, has lowered the barriers to accessing space by developing a framework that enables a global pool of applicants to rent homes on demand, in shorter increments of time and at a premium. While there has been much coverage for and against Airbnb in the mainstream media, and there is an emerging body of scholarship examining the effects of Airbnb on housing, its urban implications are contingent on context, requiring critical spatial insight and holistic analysis. This speculative design research project explores the challenges and opportunities that Airbnb presents for the future of housing in Australian cities by examining Melbourne as a case study. It asks: through strategic design and planning, can we minimize the risks and maximize the potentials of home-sharing to develop better urban outcomes to benefit locals first and tourists second? And can we leverage the global success of Airbnb to help deliver better quality, more diverse housing choices locally?

Pavilion House reconceptualizes the home as a series of rooms, to facilitate shared living, with operable furniture elements that mediate interaction between parties.

Image: Jacqui Alexander

In the last decade, the sharing economy has exploded. It is no coincidence that its two biggest players – Airbnb and Uber – were founded in 2008, following the GFC. Less production and fewer resources have forced consumption to be reconceptualized to enable a high turnover of existing products and property is no exception. Airbnb is an example par excellence of what is known in business terms as “collaborative consumption”1: a system set up to extract the latent value of assets (in this case, housing) through short-term leasing or “sharing.” The uptake of Airbnb in Australia has been enthusiastic, rapid and unregulated. Endorsed by the public and private sectors – with Tourism Victoria2 and Qantas3 both forging recent partnerships with the platform – it is now responsible for contributing $400 million to Victoria’s economy.4 But elsewhere in the world, the effects of Airbnb on the housing market are beginning to show. As a result, cities such as Amsterdam, New York and London have recently taken steps to cap the number of days a property can be listed, while others, such as Berlin, have banned “entire home” (also known as “entire place”) rentals altogether.

In Melbourne – as in other Australian cities – the housing affordability crisis has continued to escalate. A significant contributor to the current circumstances has been the post-GFC culture of investment in stable assets like property – with the incentive of tax offsets such as capital gains tax exemptions and negative gearing – which has driven up house prices and in turn rents. Rising faster than income, rents in Melbourne reached a record high in 2017.5 So what effect is Airbnb having on this already pressured housing market and what lessons can be extracted for other Australian cities? When modelled, data sourced from the Inside Airbnb website suggests that in Melbourne, Airbnb is taking available housing stock off the market where it is in high demand: in the inner city close to employment and public transport. Due to the lack of regulation in Australia, “entire homes” – which exist in large concentrations in the inner city – can be let exclusively as holiday rentals and are often listed by professional hosts with multiple properties. “Entire homes” constitute the majority of Airbnb rentals in Melbourne and data suggests that on average, they have very low occupancy rates.6 Large concentrations of vacant property – either as a result of the ebb and flow of tourism or as untenanted investments – have implications for housing affordability and supply, but can also pose broader urban challenges for local businesses, street life and security, particularly at certain times of the year.

The distribution of both “entire homes” and “shared rooms” in Melbourne corresponds with the concentration of high-density, investor-driven apartments in the CBD and inner city. “Shared rooms” only constitute about 2 percent of all listings, but they present a variety of other challenges. In Victoria, until the introduction of minimum standards in 2017, apartment design remained unregulated, resulting in a glut of poorly designed dwellings in the inner city, often with “buried” bedrooms. Considered unliveable by many residents, but attractive to itinerant tenants seeking affordable, inner-city accommodation, these kinds of apartments have found a new market as “shared rooms” on Airbnb. “Shared rooms” tend to be concentrated in a small number of isolated developments. They are often overcrowded, with two-bedroom apartments accommodating up to eight guests, and are filling a void as longer-term housing options for those who cannot access the regular rental market. Aside from hygiene-compliance risks, this kind of en masse overloading can compromise fire safety and emergency egress – issues that have been brought to the fore following the recent fires at the Lacrosse tower in Docklands, Melbourne, and Grenfell Tower in London.

More promising is the distribution of “private rooms” in Melbourne, which represent around 37 percent of listings. While these listings are still prevalent in the city, their pattern is more diffuse, expanding out to the inner and middle suburbs. Exceptions exist, but “private rooms” commonly take the form of a spare room or bungalow in a family home or share house occupied by other residents. They are also more likely to be genuinely peer-to-peer, promoting efficient use of latent space and minimizing periods of vacancy. This model comes closer to realizing Airbnb’s ambitions to facilitate more authentic experiences of place and to bring tourists and locals closer together. But most importantly, the “private room” makes great sense in the Australian context, given our predilection for large houses in the suburbs and our shrinking households. This kind of Airbnb usage in Melbourne might yield very positive outcomes, increasing the number of people within households and dispersing the economic benefits of the tourist economy.

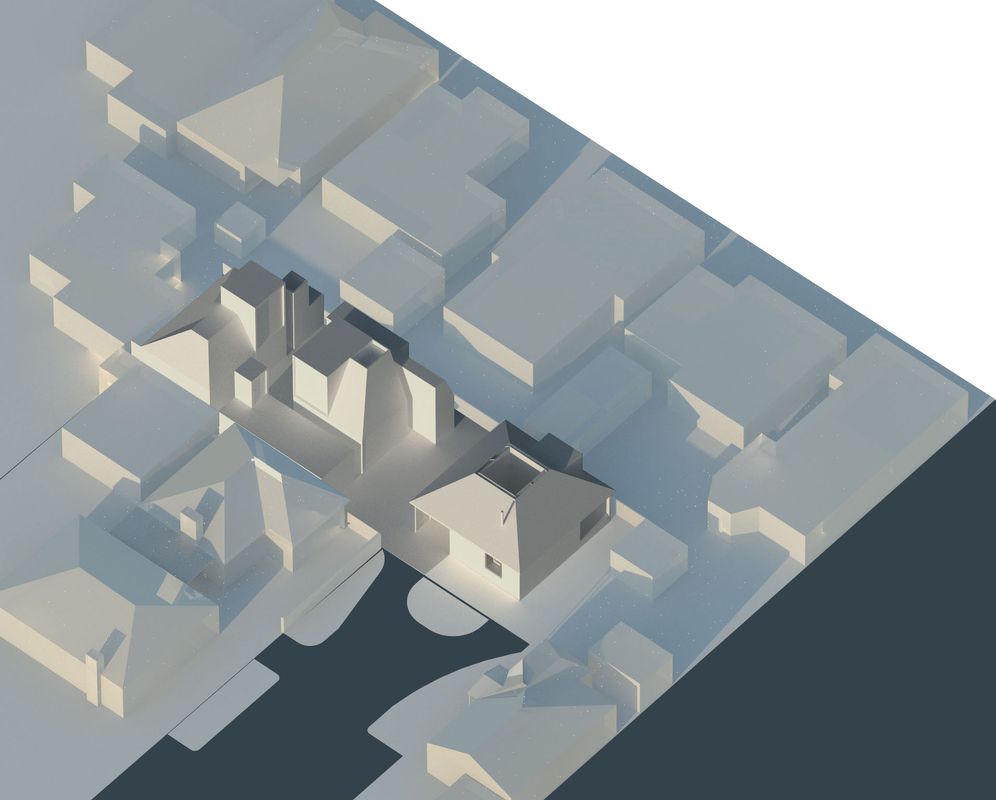

A spatial and economic model that enables expansion, Pavilion House’s parti allows for future incremental development on the site, potentially funded by income generated through subletting.

Image: Jacqui Alexander

Yet nine of the current top ten suburbs for Airbnb in Melbourne are considered “inner urban.” The popularity of these suburbs is likely owing to their proximity to public transport, on which tourists heavily rely. By contrast, if we examine the patterns of Airbnb in London – with its comprehensive, matrixed rail network – we see that Airbnb users are prepared to look further afield for accommodation. A significant obstacle in promoting peer-to-peer home-sharing in Melbourne’s suburbs is the radial train and limited tram network, making it difficult to move around, especially with the added encumbrance of luggage.

This project identifies the Melbourne Metro Tunnel and the proposed Melbourne Airport Rail Link – both earmarked for completion by 2026 – as developments with the potential to revolutionize tourism in Melbourne, in a way that could benefit visitors and citizens. The proposed airport link, which is planned to operate between Tullamarine and Albion railway station via existing freight infrastructure, could unlock the western suburbs, attracting tourists on inbound routes to the city. Moreover, the Metro Tunnel will begin to transform our current radial network into a matrixed system, introducing a direct connection between the western and south-eastern suburbs, and increasing capacity through the city. These major projects could help to decentralize tourism and, in turn, drive housing diversity.

Using West Footscray as a test case, this project proposes to leverage the popularity of the Airbnb platform to drive housing innovation and provide incentives for infill development to intensify the suburbs. While earmarked for rejuvenation in the Maribyrnong Planning Scheme, West Footscray is attractive for its ethnic diversity and, with its burgeoning Indian community, its activity centre – Barkly Village – has the potential to become a cultural precinct, like Victoria Street or Lygon Street, in the future. Encouraging tourism in West Footscray could help to reinvigorate Barkly Village, stimulating activity and revenue that could be redirected to improve community amenity and infrastructure.

A vacant site in the residential zone immediately behind Barkly Street presented an opportunity to test a new domestic prototype to support home-sharing in the broadest sense. Inspired by the outbuildings and hipped roofs that characterize the neighbourhood, Pavilion House is conceptualized as a set of “private rooms” arranged around a courtyard within a larger volume. At one hundred square metres, this compact house is designed to flexibly accommodate a range of household configurations, including a small family, an intergenerational household with dependants and an Airbnb host and guest. The dissected plan and two points of access enable more or less space to be leased on demand, equalizing the relationship between parties and preserving a level of autonomy. A series of operable furniture elements were designed to mediate access to rooms and facilitate shared experiences.

Considered as both a spatial and an economic model that enables expansion, Pavilion House’s parti establishes a formal logic for future incremental development on the site, while income generated through subletting could help fund it. With strategic coordination and cooperation from council, similar infill development could help transform West Footscray and provide an alternative to the current highrise, high-density approach.

In its short lifespan, Airbnb has wrought significant changes at the scale of the room, house, neighbourhood and city. On-demand domesticity is already changing the social fabric of the city – the question now is how to design and plan for it. Rather than imposing blanket bans or caps on rentals, this design project takes the position that with imagination, criticality and strategic planning, architects, urbanists and policymakers can respond spatially, manipulating the way that disruption occurs to limit its pernicious effects and achieve positive urban and domestic outcomes that will endure long after the tourists have left the scene.

1. Rachel Botsman and Roo Rodgers, What’s Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption (New York: Harper Collins, 2010).

2. Liam Mannix, “While Uber is illegal, Airbnb gets government help,” The Age website, 7 December 2015, theage.com.au/victoria/while-uber-is-illegal-airbnb-gets-government-help-20151206-glgm6j (accessed 14 January 2016).

3. Qantas website, “Feel at home earning Qantas Points with Airbnb,” qantaspoints.com/ earn-points/airbnb ( accessed 20 August 2017) .

4. Anthony Galloway and Alex White, “Airbnb Melbourne: $400 million a year injected into Victorian economy,” Herald Sun , 25 June 2017.

5. Kirsten Robb and Christina Zhou, “Melbourne renting: Rent at record highs, rising faster than incomes and vacant,” 10 February 2017, domain.com.au/news/melbourne-renting-rent-at-record-highs-rising-faster-than-incomes-and-vacant-20170209-gu7wpm (accessed 10 January 2018).

6. Inside Airbnb website, insideairbnb.com/melbourne (accessed 14 January 2016).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 5 Sep 2018

Words:

Jacqui Alexander

Images:

Jacqui Alexander

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2018