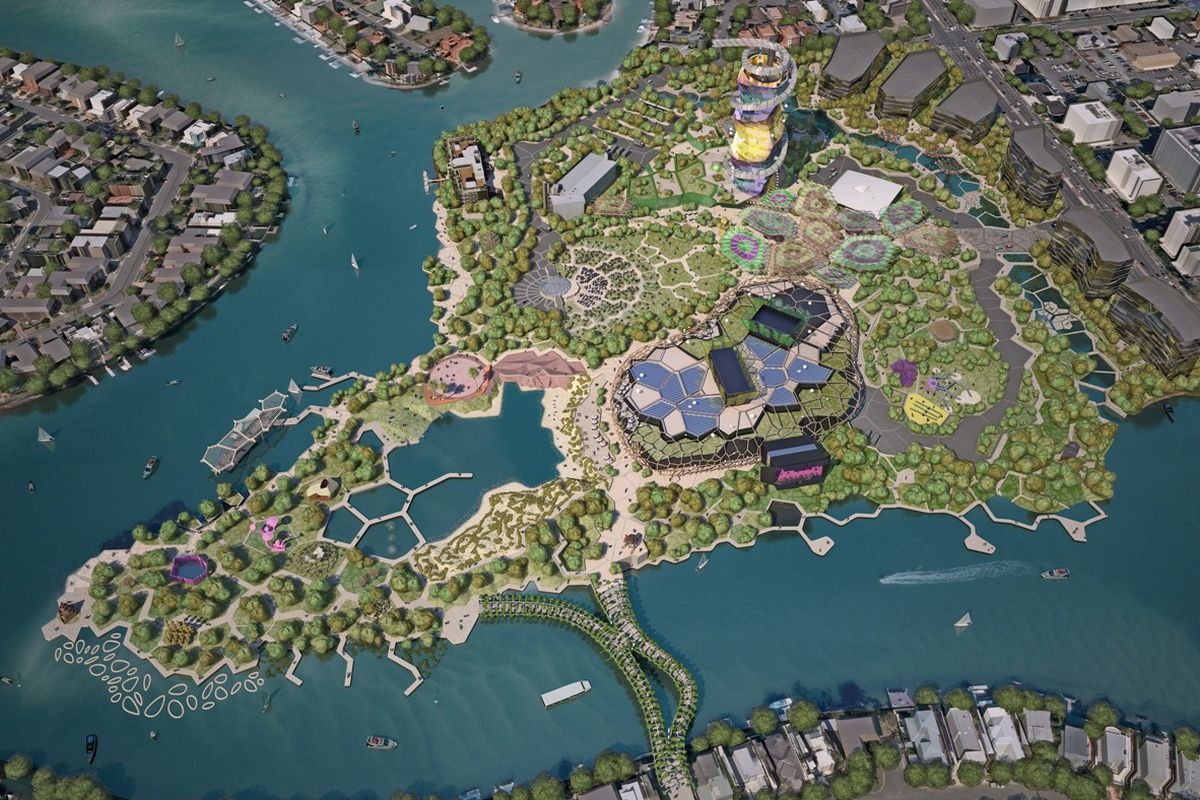

Global sporting events like the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games (GC2018) are not only about athletic ideals and reinforcing connections between seventy member nations and territories. Visitors are also invited to experience the cultural achievements of the host nation and GC2018 has prompted vast investment in physical infrastructure and cultural development programs to meet these expectations. The expansion of the region’s cultural infrastructure reflected in ARM Architectue and Topotek1’s 2014 Gold Coast Cultural Precinct Masterplan elevates the critical role architecture plays in projecting cultural identities on the world stage. Launching off the region’s so-called “blank canvas,” this vision boasts a vibrant hub at Evandale that connects cultural institutions with communities of diverse local and international spectators. However, in the staging of GC2018 and its supporting cultural vision, Indigenous culture and landscapes are arguably being downplayed against goals of plurality. This favouring of the city’s other cultural distinctions prompts the question: in the context of GC2018, should Yugambeh-Bundjalung cultural landscapes matter?

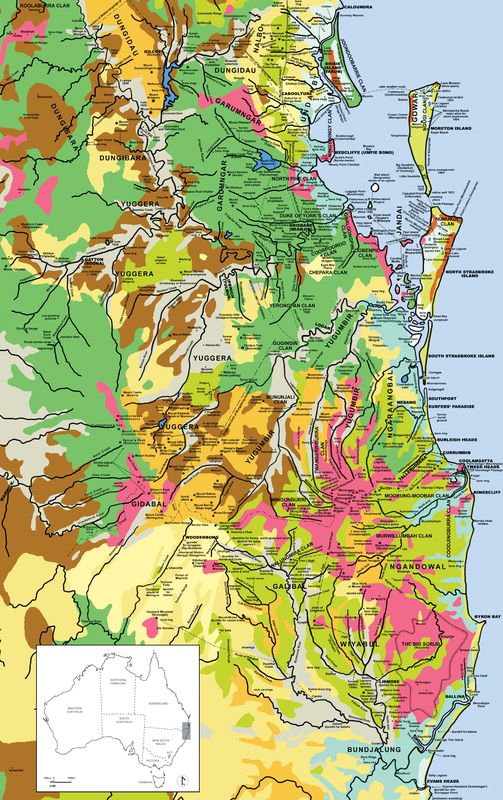

Australians and visitors are exposed to Indigenous place attachments through Indigenous settlements, everyday encounters and highly stylized cultural presentations in tourism and community facilities. The Gold Coast conurbation forms a part of what was once a large Aboriginal cultural region, broadly described as Yugambeh-Bundjalung Country. Language- specific placenames such as Nerang, Currumbin, Tugun, Coolangatta and Tallebudgera are remnant cultural markers. Two mapped examples related to the Gold Coast provide insight into lived pasts embedded in regional networks. One is Michael Strong’s 2016 archaeological documentation of several hundred bora rings in south-east Queensland, which provides evidence of intense ceremonial practices that reinforced societal order. The other is John Steele’s book Aboriginal Pathways in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River , which collates Aboriginal cultural geographies, placename definitions, linguistics, historical accounts and shared creation mythologies on the Gold Coast and beyond. Creative practices in architecture have been informed by similar historical sources, but how these become expressed in design needs to align with how Aboriginal communities presently perceive themselves.

The Gold Coast Cultural Precinct Masterplan by ARM Architecture and Topotek1.

Image: Courtesy ARM Architecture

Indigenous communities today have complex attachments and shared values that are equally invested in metropolitan places, regional centres and traditional associations. Michael Aird’s exhibition Woogoompah: My Country – Swamp Country provides a contemporary but fleeting narrative about the Gold Coast region, exploring continuous connections through descent, occupation and photographic documentation. Passing acknowledgement of Aboriginal contributions to early settlement is explored in Chris Booth’s Wiyung Tchellungnai-Najil (Keeper of the Flame) sculptural memorialization at Evandale Parklands Sculpture Walk. Insight into the evolution of touristic modernism in Off the Plan: The Urbanisation of the Gold Coast , edited by Caryl Bosman, Aysin Dedekorkut-Howes and Andrew Leach, touches on historical references to Aboriginal occupation and environmental transformations, but with scant attention to contemporary values. Tourist encounters with stylized Yugambeh cultural performances at Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary, cultural tours and the Yugambeh Museum Language and Heritage Research Centre represent a wide spectrum of cultural and economic enterprises.

Global sports are wrapped in ideals of freedom, peace and opportunity for all and the Commonwealth and Olympic Games have become calculated focal points for voicing the inequalities of dispossession or expressing inclusiveness. In Australia, the 1982 “friendly” Brisbane Commonwealth Games provided an effective platform for activists to protest and demand Aboriginal land rights. The 2000 Sydney Olympics featured Dreaming themes and imagery, marking a decisive shift in the representation of Australian identity, opening up to multiculturalism and Indigeneity. Hosting the Commonwealth Games also heightens Gold Coast pride locally and globally as a cultural destination. Major infrastructure projects amounting to $13.5 billion in state investments are designed to achieve a diffuse array of cultural and social initiatives, from public arts commissions, festivals in gateway communities, regional arts development, writing and food to domestic violence awareness. When Indigenous placemaking is executed critically, meaningfully and powerfully, such projects enable histories and contemporary expressions to have a valued presence, in the present. However, efforts to incorporate Indigenous cultural assets to enhance visitor experience are notably minimal in the Gold Coast Cultural Precinct Masterplan. Likewise, mock Indigenous fish-trap designs lost among abstracted features dispersed across the masterplan could too easily be mistaken for a piecemeal gesture. As we arrive at the cusp of GC2018, why were any opportunities to include significant Indigenous placemaking sidelined?

Adapted map of Yugambeh-Bundjalung cultural landscapes on the Gold Coast, south-east Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Image: Original maps from John Gladstone Steele, Aboriginal Pathways in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River , 1984.

By all accounts aesthetic representations of Indigenous identities in design and cultural landscapes should have reached their zenith. But on the contrary, they are gaining momentum and traction, even in private development spheres outside their usual domain. A 2014 book, Indigenous Place: Contemporary Buildings, Landmarks and Places of Significance in South East Australia and Beyond by Anoma Pieris et al, exceptionally catalogues Indigenous cultural spaces and facilities across six states and two territories. Many architectural works, from Brambuk – the National Park and Cultural Centre in the Grampians, Victoria, to Reconciliation Place in Canberra, have engaged diverse audiences in themes about reconciliation, spatial practices, memorialization and politicization. The survey unintentionally gives the impression that Australia is awash with Indigenous cultural facilities, commemorative places, artworks, civic projects and culturally inspired landscapes. The body of work in Australian architecture demonstrates that Indigenous cultural landscapes and social histories do matter. But in Queensland, and particularly on the Gold Coast, there are gaps. The Gold Coast is Australia’s sixth largest city – can this glaring gap be closed?

We hear much about missing targets in closing the gap between Indigenous Australians and others across health, employment, economic and social indices. But government policies about closing cultural gaps also occur, albeit haphazardly. In Queensland, changes to planning law may expedite gap closure, with national repercussions for architecture and land development. Until recently most state planning systems bypassed incorporating the complexities of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, cultures and traditions. Queensland’s new Planning Act 2016 has changed the status quo, requiring the architectural profession to act to protect and promote Indigenous rights and interests. Predictions are upbeat that this will spark similar provisions in planning law in other states and territories. More relevant is whether these changes will modify approaches to public and recreational space. Will the planning and architectural community have the cross-cultural skills to manage the implications? Setting this concern aside, it is worth speculating: had changes to Queensland planning law occurred earlier, would there have been more substantive responses to Yugambeh-Bundjalung cultural landscapes in the Gold Coast Cultural Precinct Masterplan visions for GC2018 and onwards?

The answer to this question is highlighted in a separate yet related panel discussion presented by Indigenous Architecture and Design Victoria and the Koori Heritage Trust, held during Melbourne Design Week and hosted by ABC radio commentator Daniel Browning. The topic was “Does Blak Design Matter?” and Browning asked, “How do we manage the paradox of building on and building up and the Aboriginal heritage values that are embedded in landscape?” A select panel of Indigenous architects and planning and design practitioners responded with the methods they employ to acknowledge, reference and engage with Indigenous place values in highly urbanized environments. The panel probed issues beyond design relevance, highlighting how projects can “value capture” by becoming a catalyst for value creation in Indigenous communities.

However, issues of culturally inspired practice and preservation of cultural landscape values are not only a matter of concern for a small contingent of Indigenous practitioners. Intercultural design competency has become a necessary skill of twenty-first-century architectural practice in postcolonial Australia, after decades of building increased recognition of Indigenous rights. Indigenous cultural landscape values have influenced cityscapes, building programs and landscape projects. Although there have been marked improvements in responding to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural knowledge and traditions, some lingering unresolved issues remain about authorship and whether the consultation methods that some architects use overwhelm or sideline Indigenous stakeholders.

Project methods and creative outcomes vary greatly between practices. Architectural researchers have criticized the approach of simultaneously territorializing Indigenous knowledge systems and alienating Indigenous stakeholders. Some exemplary projects show a convergence of the expectations of Indigenous stakeholders, designers and audiences, providing insights into how to successfully rise above place politics using collaborative and consultative engagement as a starting point. While architects and scholars generally have contributed to alternative ways of responding to the culturally specific, a small group of Indigenous architects, designers and academics has attempted to shift the paradigm beyond consultation and superficial gestures of inclusiveness that do not necessarily equal placemaking of any significance. Issues raised by Indigenous commentators indicate that while being spoken with and being heard matter to Indigenous stakeholders, other things are equally important, such as sustainable economic benefits that advance opportunities for employment across all aspects of the built environment.

Architects are not unfamiliar with additional demands infiltrating design processes. Discussions about culturally sustainable development frameworks emphasize the interconnectedness between cultural and economic dimensions. Motivations to engage Indigenous people in architectural developments in culturally specific ways may start with goals of inclusion, but need not end there. The fact that Yugambeh-Bundjalung cultural landscapes failed to matter with GC2018 and the ancillary cultural vision need not leave us deflated about future opportunities. Exemplary architectural projects that stretch beyond the immediate objectives of procurement and conclude by leaving a lasting transformative legacy for Indigenous cultural sustainability and development may yet matter.

Carroll Go-Sam will be leading an exclusive tour of the Indigenous art collection at Bond University and a panel discussion of Indigenous place making in the 2018 National Architecture Conference fringe events program. For tickets and more information, click here.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 22 May 2018

Words:

Carroll Go-Sam

Images:

Courtesy ARM Architecture,

Original maps from John Gladstone Steele, Aboriginal Pathways in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River , 1984.

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2018