I travel a lot in my role, going all around the world to lecture on green buildings. I explain that everything starts with a well-designed facade, and why dynamic passive strategies are critical to developing a high-performance building. In my travels I am well aware of the importance of dress codes. As we French say, “L’habit ne fait pas le moine.” Directly translated, “The clothes do not make the monk,” or don’t judge a book by its cover.

Well before we have the opportunity to say one word, our clothing has told a story. If this story matches what we have to say, our message is strengthened. If it doesn’t match, then we must spend time to correct the story. It’s not an easy task as the language spoken by clothes is very subjective. Culture, including clichés, fashion and past experiences, can completely change the story. To avoid this, each and every community has defined its dress codes, a “set of rules governing what garments may be worn together.” Today, dress codes are so ingrained in our cultures that for the majority of people it’s an intuitive behaviour.

Facades of buildings also tell stories. But the dress code for buildings is much less rational than the one for humans. One consequence is that lots of false ideas are promulgated around the world, and as buildings last for a long time the consequences can be tragic. A good illustration of this is the company HQ, whose photovoltaic cells were not correctly aligned to the sun because they had to face the entrance road. Someone was thinking that it’s more important that the building says, “Look, I have photovoltaic cells so I’m green,” rather than developing a genuine green building. For a building to be genuinely sustainable, it must have a tailor-made envelope, and so the new generation of thermal regulations is replacing the checklist model with simulations of the whole design.

Clothes and comfort control

Clothes are the last border we can fully control before the ultimate environment of the human body. Because the human body is the smallest and the most constant space an individual occupies, it fixes the optimum operating values for any other environments where we spend our time. At first, clothes were used solely to help the body to stay in its comfort zone. They were adapted to an activity or the surrounding conditions. Summer clothes were made with light fabrics in cold colours. Winter clothes were made with heavy fabrics in warm colours. Today, clothes remain the only comfort control system we have when we are outdoors. But we spend 90 percent of our time indoors. We live in controlled environments where it’s possible to create comfortable conditions whatever we wear. People can dress on aesthetic criteria. However, for some activities the stories told by clothes must remain coherent. It’s from this need that the concept of dress codes emerged. When dress codes become rigid and disregard climate and seasons, we expect building systems to take the load. Consider Japan, where the prime minister had to advocate for a short-sleeve, no-tie summer dress code for salarymen. This simple gesture could save around two million barrels of oil during summer.1

Why not a credit for intelligent dress codes in green buildings rating systems?

An intelligent dress code doesn’t define each and every garment. It allows people to choose from within an acceptable range of garments. A dress code has to deal with multiple variables: gender, activities, the seasons, our surroundings, etc. In choosing an outfit, we anticipate the worst-case scenario or the average conditions for the day. But weather is unpredictable. Cold summers, rainy summers, warm winters, sunny winters all happen. These approaches are right on average but not on a daily basis. Someone strictly following a dress code defined in this way will hardly ever be in extreme discomfort but conversely will hardly ever be in great comfort.

An intelligent dress code specifies only the style and colours while guaranteeing the message. The whole “system” should be comfortable to wear outside. Of course, if the outside conditions are really bad, for example if there is heavy rain or extreme temperatures, extra accessories such as a coat, umbrella or a hat can be added, but nothing that changes the performance of the clothes too much should be included, so as to keep the indoor comfort conditions as close as possible to the outdoor conditions.

It’s amazing how far the analogy between building envelope and clothes can be taken. Both are defining the border between the outside world and the environment where we spend the vast majority of our time. Both have to protect the space we occupy. When we think in an ecologically sustainable manner, both must play with natural energies and elements available to us before anything else is considered to make this space where we live healthy and comfortable. The biggest difference is that within buildings there are many active solutions available that bring the building back into nominal values when passive solutions can no longer maintain it in the comfortable range. In modern buildings nearly three-quarters of energy consumption is to keep the indoor environment quality within the acceptable range of values.

Dress code for green buildings

Considering that facades are to buildings what clothes are to the human body, we see a new vision of what constitutes a well-designed facade and so of thermal performance regulations. Like traditional dress codes, traditional thermal regulations define specifications for each and every component of buildings. They are defined according to the mean worst cases. It works on average but limits are soon reached when higher performance is needed. In fact, it’s as if you were using hat, scarf and coat all year just because you need them for a few days in winter.

Modern thermal regulations are like the intelligent dress code. They define the objectives and let the architect work with the engineer to choose the right design according to local conditions. To guarantee the results, the objectives are described in terms of bioclimatic coefficient and total primary energy consumption per surface unit and per year. A bioclimatic coefficient indicates how well designed the core and shell of the building are (i.e. how well the passive strategies are used).2

So, the dress code for buildings to be green is a set of passive strategies, especially of dynamic passive strategies. These strategies allow truly green buildings to tailor their indoor environments to be the most healthy and comfortable for their occupants while delivering quantifiable energy savings.

Dynamic facades – an active solution

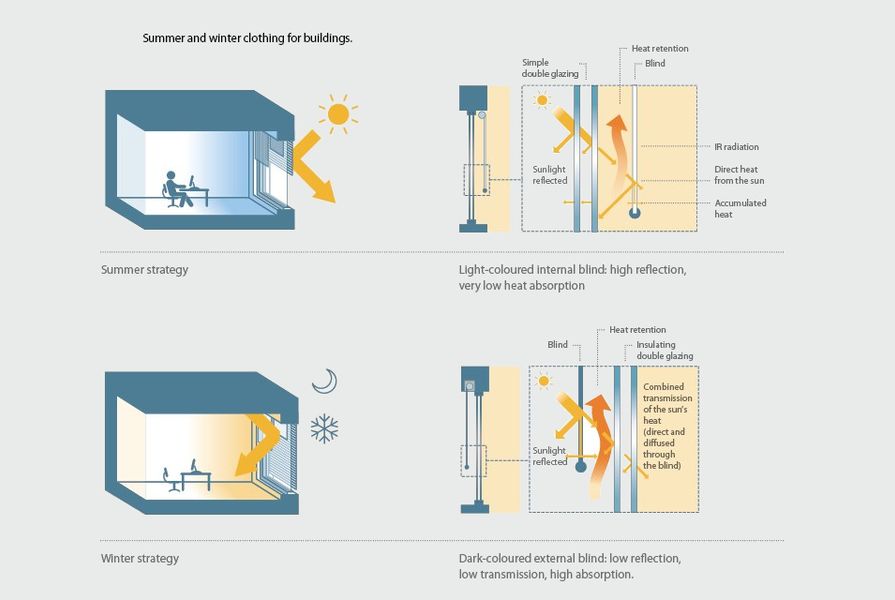

Just as people can quickly and easily adapt their clothing to suit the environment, so too can a building. By using dynamic passive strategies, building designers can ensure that the facade’s clothing can adapt to the minute-by-minute changes of its environment. Whether the building needs to gain heat on a bright but cold winter morning, protect its occupants from the harsh summer sun, insulate to retain heat on a cold winter night or purge excess heat on a summer evening, only a truly dynamic facade can allow the building to adapt its clothing. Aesthetically, the facade of the building as a design statement also makes a clear statement about the building’s dress code. Should the building look like a messy teenager? Or is it a smartly designed, transparent window into the ethos of the company?

Automated facades controlled by a facade or building management system are a proven technology worldwide. Actuators and control systems are fit-and-forget entities, with product life cycles equal to or greater than many products used in modern high-performance buildings. Just as chilled beam and green concrete technologies have revolutionized the way that designers can reduce the environmental impact of their building during the construction and operating phases, so can an active facade. The dynamic facade brings indoor environment quality gains while also allowing designers to showcase the changing moods of a building as it reacts to its changing environment.

1. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/11522280/ns/business-oil_and_energy/

2. Several new regulations (e.g. French RT 2012) define their way to establish the bioclimatic coefficient.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 23 Aug 2011

Words:

Serge Neuman,

Alistair Grice

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2011