Point Lookout, at the northern tip of North Stradbroke Island is a unique and beautiful place on the eastern Australian seaboard. On a clear day there are panoramic views many kilometres down the southern surf beach - all the way to Surfers Paradise. It is a coastal utopia that is occasionally contrary; the weather is not always benign. Wild south easterlies can blow spray through your Drizabone and cyclones are a ubiquitous hazard.

Stradbroke’s stunning natural features and climatic extremes offer enticing environmental design opportunities - particularly for two architects!

Jennifer Taylor has a long-standing reputation as an educator, researcher and architectural historian. Her work has been acknowledged by two inaugural awards: the NSW RAIA’s Marion Mahony Griffin Award in 1998 and the RAIA Education Prize in 2001. Some, but not an equal number of people know of her considerable architectural design abilities. In the 1990s Jennifer designed a new house incorporating three existing sandstone walls at Palm Beach, New South Wales. It was while photographing this project that I first realised that Jennifer’s knowledge of architecture is not confined to the reading of architectural history and theory texts. Her Palm Beach project demonstrated an exceptional ability to order structure, space, colour, texture and detail in a manner similar to her accomplished writing about Australian and international architecture.

Jennifer subsequently moved to Brisbane where she took up an adjunct professorship at Queensland University of Technology’s School of Architecture in 1998.

She had been working intermittently on the design of Dunbar for about ten years during visits to the old “fibro” cottage on the site. Final drawings were completed during a twomonth study break in Bali in 1997. Shortly afterwards, her partner Jim Conner contributed his documentation and contract administration skills to the project. Their combined talents have resulted in a unique Australian house. Here are some of my photographs and written impressions.

Dunbar reveals its spectacular prospect and subtle details in a slow, carefully orchestrated sequence of moves, similar to the experience of a traditional Chinese garden.

Arrival is via a narrow gravel lane reminiscent of holiday allotments of the early fifties.

Casuarinas, banksia and pandanus palms screen a similarly coloured single-storey rendered wall. Three screened openings permit views through the place, enabling passers-by to look right through the house. They can even “check out the surf” if they’re impatient! The main gable roof, with its clerestories and secondary skillions, is clad in a specially rolled profile. A vine tumbles over the screened entry gateway. The street facade is low scaled - quite understated.

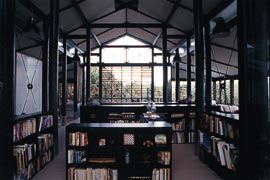

Through the gate, and “inside” is a sequence of two courtyards. The first of these is a pebble-finished transition garden; the second is spacious, paved and central - conceptually similar to the atrium in Roman architecture. The street’s surrounding boundary wall gives way to a “forest” of fifty robust, circular, pinus radiata timber columns. Looking up, the sky’s scudding clouds or zenith blue are framed by the cut-away gable of the main roof. This pivotal courtyard is a mediating space, a void, and, at the same time, the plan’s hub. I’m reminded of Lao-tse’s economical prose, “The wheel’s hub holds thirty spokes. Utility depends on the hole through the hub.” So, what are the spokes and the utility in Dunbar’s case? Two double rows of ink-green columns define the courtyard’s land and sea edges - connecting and sheltering the kitchen and main living space on the west and the library and (downstairs) guest accommodation on the east. Dunbar is far from a simple beach house - it serves as a place for the casual and formal entertainment of friends and colleagues, as a writer’s retreat, a fisherman’s base and a home away from home.

My overarching impression is that Jennifer and Jim have imaginatively blended the substantial, timber-framed order of traditional Japanese architecture (and other eastern models) with the generous volumes of an Australian shearing shed. Of course, there are differences between the reality of the architecture and this rather crude analogy, yet, for me, the link remains. Jennifer specifically comments on some of these influences. For example, “the volumetric/spatial order was inspired by the Sri Lankan dana salarwa - a space that is an open colonnaded extra-wide passageway/room that also serves as a series of spaces to accommodate different activities. Its appeal lay in its dual nature, being both dynamic in totality, yet with the potential to be static in its parts.” Indigenous Balinese architecture was also a stimulus, as she lived in its midst as the final drawings were prepared. The houses of Japan and the gardens of China were

influential too, and Jennifer has lived and worked in both those countries. No doubt memories of the wide-open verandas and other aspects of the Queenslander in which she grew up were subliminal sources of inspiration as well.

In addition to formal, spatial, and environmental resolution, architectural excellence is characterised by thematically related and finely resolved details. Dunbar demonstrates detailed care with design elements. This can be appreciated in aspects such as the careful proportions of frame and plane, the absence of a potentially clumsy sub-frame between column and door, the elegant stainless steel collar between column and slab, in the transparent/translucent roofs over the showers and in all manner of built-in furnishings.

Generous light (and ventilation) levels are an important departure from the rather subdued illumination of Japanese houses. Light and air enter the plan’s centre via north and south clerestories while combinations of glass and opaque louvres may be adjusted to alter the quality of perimeter light and the extent of view. Library and living room doors fold back - these walls may be “dissolved” and, if appropriate, the two pavilions can be visually and functionally interconnected to the central courtyard. This combination of devices allows the house to breathe freely, really freely. In order to do so efficiently, doors and louvres must be adjusted by a knowledgeable operator. Jim tells me he was a mad-keen sailor - one therefore understands his need to metaphorically “trim the main” or to use a storm jib depending on the weather.

This house has its mechanisms, but the impression is not of a “machine for living in”.

Rather, I recall the seminal modernist Luis Barragan who stressed the importance of architecture’s need to offer refuge, modesty, beauty and technical validity beyond mere convenience - particularly with the integration of gardens. Serenity was his main objective.

I’d confidently speculate that, like me, Barragan would have been pleased to experience the calm sense-of-being that Dunbar engenders in its owners and its visitors.