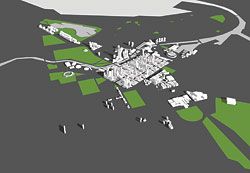

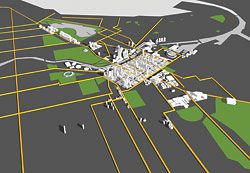

Three-dimensional models showing how the new paradigm might be implemented in Melbourne.

How might Australian cities be reconfigured to meet the challenges of climate change? Rob Adams argues that the answer is in the sprawling metropolis and advocates dense, sustainable corridors.

We will remember 2006 as the year the world woke up to climate change – an inconvenient truth. Ever since, our search has been for big new solutions for a big problem – billion dollar solutions, often untested. In this context it may seem naive to suggest that the solutions might already exist and that they are not necessarily expensive.

Over 80 percent of Australia’s population lives in cities. Our cities are also responsible for over 70 percent of the country’s emissions. So if we are to assist in taming global warming, we need to make our cities liveable, sustainable and economically viable. To achieve this, we need to realize that 80 percent of the infrastructure that will exist in cities by 2030 already exists today. The larger challenge is therefore how to reconfigure our existing infrastructure to achieve a sustainable future. Given that 80 percent of our future cities already exist, is it possible that the sustainable city already exists?

If I were offered the opportunity to take any city in the world to zero emissions by 2030, I would choose Barcelona. Why? Well, with 200 people per hectare, Barcelona is one of the world’s most dense mixed-use cities. It enables residents to service all their needs locally on foot. It has 40 percent open space made up of fine streets and public spaces that sustain a vibrant social and cultural life. Streets are well serviced by public transport, which makes owning a car a liability. All of this vibrant life is contained within a uniform built context of seven storeys. Every building has equal access to the sun – the most abundant renewable energy source. A simple conversion of the roofs of Barcelona to solar collectors would go a long way toward zero emissions. This suggests that sustainability is possible and, given that Barcelona is not a bad place to live, it need not be the “hairshirt” existence many of us fear.

We have reached an interesting time when the drivers of sustainable cities are the same as the drivers of liveable cities. These are density, mixed use, connectivity, high-quality public realm, local character and adaptability. When these characteristics come together in a city as they do in Barcelona, they provide an alchemy of sustainability, social benefit and economic vitality. These cities reduce the need for car travel, lower energy consumption and emissions, use local materials, support local businesses and create identifiable communities. These are just a few of their benefits.

So, how can this inform Australian cities? Central Melbourne is recognized globally as a city that has, since the early 1980s, moved steadily toward a more sustainable and liveable future. With its new residential population, improved public realm and transition from a central business district to a central activities district, the centre has many of the positive qualities of cities like Barcelona.

The example set by Melbourne has started to be replicated by the other Australian capital cities. Assuming they will be successful, the challenge is no longer the city centres but, rather, the sprawling metropolis. How can we reconfigure the suburbs and the fringe at a time when the increasing cost of petrol and the tyranny of distance are making these areas ever more difficult for their citizens in financial, social and environmental terms?

Containing our future development and infrastructure within our current city boundaries while achieving greater efficiencies and affordability is every Australian city’s aspiration. Achieving this has to date eluded us and will in the future become the litmus test of our commitment to succeed in the race for sustainability.

Current state government strategies of increasing densities in activity centres and around transport hubs attempt to do this, but have failed under the pressure of increasing population pressures and the need to provide affordable housing solutions. The default has been to extend city boundaries, further subdivide farmland and exacerbate the problems of both affordability and sustainability.

The principle that activity centres need to be developed as mini versions of central cities, with higher densities, quality streets, a mixture of uses and good access to public transport, is a welcome move in the right direction. In achieving these qualities, activity centres will move towards providing part of the solution to the increasing demand for housing and easy access to goods and services. If this current strategy were to be expanded by connecting all activity centres with a network of high-density corridors along all the existing and proposed public transport routes, we would have a far greater likelihood of success. This success would be further ensured if planning controls were amended along these routes to provide as-of-right development to a height of between four and eight storeys and to the depth of one site (or fifty metres). Heritage buildings and public parks would be protected. With limited car access, the road space would be calmed in favour of public transport, bicycles and pedestrians. If the increased value of these properties was partially captured and used to provide affordable housing, then this approach would deliver a web of high-density, mixed-use corridors linking activity centres. This web would be supported by a quality public transport system within easy walking distance of the adjacent suburban areas. The need to own a car would therefore be limited.

The next challenge would be to position the adjacent suburban areas in a more positive light. These should become the new “green wedges” where increased input tariffs for green energy would make the generating of energy a financially beneficial endeavour, as is the case in Germany. All households would become mini power stations feeding green energy into the grid during the day while the majority of the population is at work and then drawing it out of a base load at night or from batteries stored within the house. This would maximize the efficiency of the existing power distribution infrastructure and minimize the need for future coal-fired power stations. If you consider that a fifty-square-kilometre solar collector is sufficient to service the total energy needs of Australia, it is not hard to imagine that our suburbs would be part of the solution. In addition, streets could be planted with more trees, providing sequestration, and water could be collected and reused. Not only is the city a solar collector, with its hard surfaces it could become a catchment, and thus a positive contributor to our water supply rather than just a consumer.

This approach would see a new paradigm for city development – a paradigm that no longer draws the differences between suburbia and urbanity but one that recognizes both their strengths and weaknesses and combines them to form a more robust model of city development. To achieve this we would need to amend planning laws and building procurement costs to favour the ten percent of our urban areas that are adjacent to transport corridors. These key development areas would become the urban skeleton containing jobs, affordable housing and services currently lacking in our sprawling cities. The remaining ninety percent of our cities would be designated areas of stability, attracting incentives to become areas generators of renewable energy, collecting their water, reducing their waste and increasing tree plantings and backyard productivity.

Clearly we require a big shift in our perception of cities and infrastructure. We need to break the myth that higher densities mean high-rise development. As Barcelona and other more recent examples such as Bo01 in Malmö, Sweden, have shown, very high densities and sustainable urbanism can be achieved with developments as low as five storeys.

The more significant shift in perception is that our cities are best served by large-scale infrastructure. The current thinking that power generation and water supply can only succeed through the provision of large, centralized infrastructure limits our options and ability to not only climate-proof our cities but also defend them against the increasing threats of extreme circumstances. Smaller, distributed solutions are not only more efficient and economical in their requirement and use of distribution networks but are also, as a result of their distributed nature, less vulnerable to extreme circumstances.

Large-scale government-sponsored infrastructure also has the insidious side effect of disenfranchising the wider population. The solutions to global problems of climate change move beyond the reach of the individual and become government problems – not our problem – thus working against the cultural shift we need to make a paradigm shift.

So can the proposal described above excite governments to think about our cities in a different way? Maybe not, because they are not expensive enough and don’t stand out on the landscape. Their subtlety is their greatest opponent. The fact is, given a chance, they could work. Just as central Melbourne improved its global standing over twenty years through the transformational application of good urban design, so too could our cities of the future reposition themselves by 2030 through transformational changes. Studies carried out on metropolitan Melbourne show that the dense corridor development described above could accommodate over two million people without any loss of heritage fabric or any expansion of the city boundaries.

With its relatively strong economy, Australia is uniquely positioned at a time of global financial crisis. Australia could leapfrog its European cousins by setting strategies for future infrastructure development that would not only strengthen and broaden our technological base but place us at the front of the field in future city-making. Twenty billion dollars invested in conventional infrastructure will only give us conventional outcomes. The same amount invested in “new age” technologies could see us become a world leader. We need to move from the sheep’s back and mining resources to the suburban roof.

Professor Rob Adams AM received the Prime Minister’s Banksia Award for Environmentalist of the Year in 2008. An earlier version of this paper was published in The Age in May 2008.