IN PART TWO OF HIS ESSAY, PAOLO TOMBESI CONSIDERS THE OTHER SIDE OF THE ARCHITECTURAL EXCHANGE BETWEEN AUSTRALIA AND ASIA: AS SERVICES ARE EXPORTED, STUDENTS ARE IMPORTED.

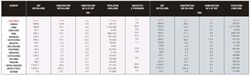

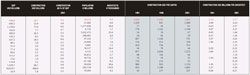

Population figures are from the World Development Indicators Online Database of the World Bank. GDP and construction volume data are from the National Accounts Database of the Statistics Division of the United Nations and reflect output value at current prices in US dollars. Architects’ numbers in 1991 are based on a survey administered by UIA in 1992. Those in 2001 were collected by the Collegi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya. Although comparable in principle, the data must be taken with a grain of salt due to differing national classifications of architects and the means of calculating construction activity.

HISTORICALLY, THERE IS a connection between growth in the construction sector and surges in the architectural education market. This is partly because of the need for more practitioners and partly because of the earning potential generated by the increase in per professional capita spending against otherwise comparable occupations. This was the case, for example, in the US in the 1950s and in Italy during the economic boom of the 1960s. Over the last fifteen years, urban development trends in Asia, and particularly its low-income economies, have produced a similar situation on a much grander scale. This has been further emphasized by the transitional nature of the underlying changes, which have taken most of the region from state-planned economic structures to ones based on individual entrepreneurship.

The relationship between professionally mature Australia and its northern neighbours has consequently become a two-way exchange – based on the export of services and the import of students. The two are almost comparable in terms of contribution to the GDP.While the export of architectural services may be close to 10% of the sector’s revenues, architectural training is already believed to add the equivalent of 7% of the overall value of domestic architectural services, when students’ living expenses are included. Besides, it is poised to allow further growth, hinting at a not-too-distant future when local and foreign student numbers will balance each other.

But can professional education be transnational? Should it be? In architecture, the relationship between academia and practice is important. The theoretical framework of architecture cannot be detached from the socio-technical predicaments within which it exists.

Knowledge of specific tools and operational dimensions is necessary to define a critical metier where the rhetorical and the technical combine. One could almost say that architecture can’t avoid being “organic” to its own context. Not in the sense popularized by Frank Lloyd Wright (working within the nature of specific materials and settings) but in the broader sense employed by the political philosopher Antonio Gramsci. That is, grasping the relationship between the work itself and the way this work informs, and is in turn hindered or made possible by, its own economic, technical and social environment.

Within this framework, the role of universities is to intersect with and enrich practice: to create intellectual resources that are more or less aware of their function within a territory, aligned with particular technological contexts and able to generate informed and thus applicable critique. Good professional education has traditionally reflected geographic belonging, with the application of general ideas and deontological principles to the problems, needs and techniques of local practices. Schools were professional not so much in the accreditation of their degrees as in their attempt to define the intellectual scope of what one should profess locally and in providing the relevant training.

The question today is whether the “local” can be asserted in a thorough, critical, professionally meaningful sense when the educational environment needs to respond to an extremely heterogeneous geography, and where student demographics imply major environmental dislocations.

The expansion of the student body to incorporate a vast international population generates practical problems in architecture’s professional education. It makes the organization and delivery of “organic” curricula difficult in terms of time, academic resources and relevance to students, with the result that many programmes are moving towards a less structured, more articulated, range of offerings. The situation has its pros and cons. Students go through educational experiences that sharpen their minds and expand their horizons but that also restrict their understanding of the specific challenges of their locales. This puts many of them at a loss after graduation, or in a passive position towards existing modes of practice.

Of course the intellectual mandate of architectural schools is not limited to workforce generation. But student demographics – and thus the size and number of architectural schools as we know them – are closely related to registration criteria. If architectural education were to move out of universities and back to the apprentice system, the number of students interested in studying the discipline as a fine or liberal art would drop to a fraction of current enrolments.

The educators of the English-speaking world know this very well: the expansion of the student body has coincided with shifts in the political economy of accreditations, itself a sign of the times. At mid-century, partial exemption from RIBA’s examinations was a way of affirming school status and enticing students; today Australian universities (along with their UK and US counterparts) seek recognition from national institutes around the region. In this sense, the issue of professional preparation can also be construed as a contractual if not ethical issue.

The international bodies and national organizations working toward global trade in professional services seem content with a generic view of architecture, which revolves around the satisfaction of formal requirements. For example, the two documents prepared by the International Union of Architects (UIA) – the Accord on Recommended International Standards of Professionalism in Architectural Practice approved by UIA members in Beijing in 1999 and the Charter for Architectural Education endorsed by UNESCO in 1996 – depict a humanist but abstract idea of practice which is essentially comparable between geographic zones. The associated checklists assume an ability to find equivalence between programmes. Length of education and training are given an ideal measure (5 plus 2), while the profile of the future architect is considered absolutely, as an indivisible unit, without ever relating it to particular divisions of professional labour that may characterize (by choice or by necessity) the practice of architecture in specific places. Post-apartheid South Africa, for example, recently adopted a four-category professional education/registration system, from architects to draftspeople, which makes perfect historical sense but hardly fits UIA categories.

Australian education marketers implicitly adopt the position that architecture is but one of many academic specialties, emphasizing simple quantifiable advantages such as geographic proximity, cost, duration of education, and transferability of qualifications, while downplaying territorial specificity and professional affinities (or lack thereof). The pressures to take advantage of the “exchange value” of architectural education are real (especially in times of limited government support to universities) and in line with the commodification of the global service sector as a whole. But this produces a paradox – the more the demand for professional education grows, the more detached its providing institutions become from localized professional “activism”.

While work specificity, cultural cohesion and the cultivation of precise expectations help students build expertise, professional markets also build natural entry barriers. For example, in Denmark, Finland, Norway and parts of Switzerland (where neither the architect’s title nor the supply of architectural services is protected, and where living costs and design percentage fees are higher than Australia’s) foreign competition is scarce: the efforts required to match characteristics and expected quality of output are excessive for external providers.

In other words, architectural markets can be protected by the construction of an industrial regionalism, committed to a form of architectural production peculiar to the place but not enslaved to it. This finds a suggestive parallel in development economics, where institutional regionalism is widely considered a natural and effective reaction to global pressures. But how can you make this happen in the current environment? Is there a way to help students and make the most of international flows while controlling the difficulties these may cause to the balance of a meaningfully professional education?

I believe there are two options. The first is to bow to the socioeconomic realities of architectural practice and building production, acknowledge that most building design will become increasingly standardized and supplied from the lower-wage centres of the professional world, and turn architectural curricula into non-applied, arts-like degrees by stripping them of any regional professional component. This would maximize the number of international students that could enrol in them. Local students could then be redirected towards areas with high value-adding and export potential, such as the industrial design of building systems, or services with strong place-based or culturally specific constraints: urban or landscape design, interior design and urban planning. This in fact provides a snapshot of where the profession is actually heading in parts of North America and Europe. The other option is less drastic but geographically more ambitious. It consists of a combination of steps that reinterpret the categories of service supply envisioned by the WTO General Agreement for Trade in Services (GATS), which Australia appears to support so wholeheartedly.

The first step is to switch mind-set and concentrate on architecture’s “use value” by creating and disseminating knowledge that responds to determinate conditions. Each university could establish a student collection basin that reflected broadly understood environmental affinities between itself and other locales. This would build an effective link between international training and domestic practice without penalizing any student, since local curricula would need not be altered in order to become international (or relevant).

Instead or as well, institutional networking could be implemented within the same metropolitan area by allowing international students enrolled in one architectural school to take courses in all the others. The combination of resources would greatly expand the flexibility of curriculum design (and the outreach potential of the education) without compromising the academic disposition of each institution. Harvard and MIT, as well as the Los Angeles area schools, have done it for decades with great success. Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney could easily follow with their own clusters, and in the process build contextual, technical and critical mass.

Thirdly, professional education could be moved offshore whenever possible, close to the source of students, and administered in conjunction with local structures. This is often considered a prelude to the relaxation of academic standards, and it may well be the case in other disciplines. But in architecture, the demand for education reflects real physical, environmental pressures, which students can start to address while in training by using their home territory as a laboratory. This strategy would take Australian schools away from global cities or regional centres and towards “second tier” or “third tier” towns, because it is here that construction is radically changing the environment and professional education less established and more needed. But this could be turned to great advantage. Australian firms with professional interests in the region could become involved and assist in this type of work based on their specific skills and perhaps local collaboration needs, thus returning training for professional opportunities. Australian students and continuing education practitioners could also take advantage of these settings, to expand or hone their skills and develop applied research work. The existence of offshore set-ups would help foreign students choose educational options based on their needs and perhaps possibilities. Those with an interest in regional practice could study locally, while those with an interest in academic training or post-professional qualifications could travel to Australia.

For this to work, intellectual generosity and cultural investment are necessary, and open courseware information critical. By making every piece of teaching and research available free on their websites (as many departments at Harvard and MIT have done), Australian universities would build an intellectual community and contribute to its development while planting seeds for truly higher education. Prospective students could use online access to raise their levels of information and disciplinary preparation and gain a better understanding of the institution selected. At that point, trading barriers would be lowered and academic bars raised to the benefit of everyone.

PAOLO TOMBESI IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE. PART ONE WAS PUBLISHED IN THE PREVIOUS ISSUE.