Photography Mark Ashkanasy

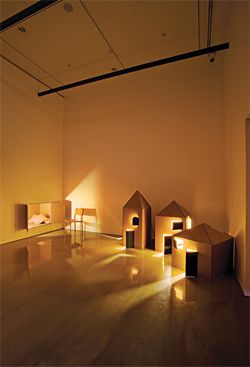

An overview of the Shelter: On Kindness exhibition at RMIT Gallery. On the left is LAB Architecture Studio’s Safe-House. To the right is Gregory Burgess and Pip Stokes’ yellow beeswax installation, Sense. March Studio’s shelter is seen in the background.

Interior of March Studio’s “fort” made from four-by-two planks “smelling of farmyard hens”.

Charles Anderson’s ceiling installation, a patchwork of ceilings.

Peter Corrigan questions the duty and “mother knows best” attitude of architecture.

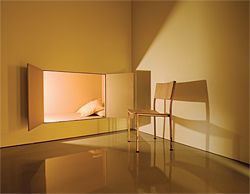

NMBW Architecture Studio’s “corner of kindness”, which reflects on the theme of homelessness.

NMBW Architecture Studio’s “corner of kindness”, which reflects on the theme of homelessness.

Hélène Frichot and Michael Spooner consider the recent show at RMIT Gallery.

Kindness smells of beeswax; the stink of a chicken coop; torn cardboard that has been pissed on by little children; discarded mattresses; the dampness of thick, grey felt; bushfire-burnt, charcoal-encrusted battens of wood; and pussy willow. When it is most mawkish it heaves like strawberries and cream. When it arouses the most discomfort, it has lips like a wet fish and its exhortation to you is: be kind! These sensations and more are excited in the exhibition recently shown at RMIT Gallery, Shelter: On Kindness. The brief offered to the artists and designers was in the form of a book by Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor, entitled On Kindness. Take care: kindness is not all that it seems, and similarly, shelter is not necessarily a gift that requires no return.

The history of kindness, as Phillips and Taylor argue, is fraught, especially when it comes to our contemporary context, characterized by the will to self-sufficient individualism. The logic of the free-market capitalist economy demands that exchange value is paramount – everything is measured “in kind”. Kindness demands some return, even if that return is merely the warm feeling you get having expended yourself for a brief moment in being kind. What’s more, just when you, the architect or designer, thought you were being altruistic by extending the gesture of shelter, perhaps, after all, you were just showing off your design expertise. A strangely ominous fort by March Studio styled from an enormous stack of re-purposed four-by-two planks smelling of farmyard hens not only offers shelter, but expresses the might of architectural form. The archetypal Aussie four-by-two plank can also be used to knock you over the back of the head.

It’s a dog-eat-dog world, a Hobbesian vision of men [sic] as self-interested, survival-anxious wolves made inexorably manifest: this is our twenty-first-century milieu, eat, be eaten, or spit it out if you don’t like it. Men and animals dig burrows and trenches to shelter from marauding, unnameable enemies. If you know who is on your side, then you also know to whom you can express a modicum of kindness. Lab Architecture Studio has composed a burrow lined in grey felt, and spiked with plastic cable ties, after Kafka’s short story The Burrow. Its lascivious folds resemble a Joseph Beuys prophylactic gone awry or a plucked feminine. They have also drawn our attention to the prison and the refuge as forms of shelter. Anne Frank’s diaristic murmurings of adolescent sexuality aroused in the midst of her annexe are placed perilously alongside the Marquis de Sade, who takes shelter from polite society in order to explore his sadomasochistic routines. As psychoanalysis tells us, kindness and desire are bound up in a complicated association of ideas and urges that we must untangle as adults so as to avoid killing our father and marrying our mother (or vice versa).

There is the admixture of kindness and desire in Charles Anderson’s ceiling installation, a patchwork of ceilings that have sheltered the long history of his itinerant journeys. Imagine the lovers who gaze up secretly at Anderson’s ceilings, and, from an imagined topography of old mattresses, whisper, yes, I remember that moment of kindness too!

The emphatic shakes of a single yes burst forth in a rolling yes, yes, yes! as William Eicholtz’s pediments grasp rolling mattresses in an onanistic gesture of bulging strawberry bodies in heaving cream. As with Anderson’s ceiling you will miss these pediments if you don’t look up. The erotic desire that can be associated with kindness allows our sympathy to extend from self-love to love of the other and rebound back again.

Where are you most likely to discover the shelter of kindness? Woman and her chore as primary caregiver to children (yes, even today) is the sanctuary where kindness is still to be found. And children themselves are capable of spontaneous acts of kindness (as well as cruelty).

NMBW Architecture Studio’s corner of kindness reflects on the theme of homelessness by revealing a punched-out cardboard cubbyhouse in the gallery wall, as well as laying out a little suburb of cardboard houses glowing from within. This will be every child’s favourite and look out for the picture books! Women and children also feature in the Indigenous corner of the exhibition. A Waramirri baby in north-east Arnhem Land sleeps soundly beneath a curve of woven grasses that will later be wrapped around his mother by way of a skirt.

As the gallery doors were only just opening to the public, the busiest hive of activity was the construction-in-progress of a tea-house designed by Terunobu Fujimori and Jun Sakaguchi. A bulbous, black-and-white body smelling of wet plaster and the charred vestiges of the Victorian bushfires has been elevated atop five dark bestial legs like a John Hejduk masque. Students assisted in the collection of the charred bushfire timber that clads the tea-house and, with local construction workers, volunteered their labour to complete the building work as a gesture of collective kindness. A ritual of collaborative endeavour extends from construction to the tea ceremony itself, and kindness emerges through the collective spirit that singles out no one individual, nor any transcendent being.

Ishmael contends in Moby Dick that “Christian kindness has proved but hollow courtesy” and so he turns to his pagan friend Queequeg for other expressions of kindness. Likewise, lapsed Catholic Peter Corrigan seems to be asking whether duty and the “mother knows best” attitude of a profession such as architecture must be tempered. In Corrigan’s vision, too easily dismissed as theatrical, the mother and her wagging finger have aged. Sitting on a red kitchen chair, maternal kindness has been reduced to a puppet in plastic couture with the head of an old fish demanding to be kissed. Around her elevated stage are four exclamations of kindness: Be Kind, A Kind, In Kind, Kinder. The last could be misread as the German word for “children”, but do children have an innate sense of kindness or one that is manufactured through societal norms? Should we be kinder still, with an excessive kindness that is empathetic and generous, a kindness that leaves no-one wanting? Kindness is not something that happens through the actions of a built structure alone, however generous the offer. It is at one end of the spectrum a long wait for an unknown, a wait that may overshoot or fall short of the mark, and at its other extreme, kindness can strike its target fatally: the proverbial killing with kindness. Before you dismiss Corrigan’s puppet, call to mind the closing scene of Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire. As poor Blanche the crack-up – still in search of her ideal beau – is being led away to the loony bin by a kindly doctor she exclaims, “Whoever you are, I have always depended on the kindness of strangers”. After all, what do architects depend on most if not the kindness of strangers daring enough to realize their mad-as-March-hare schemes and ambitious plans?

Hélène Frichot is a senior lecturer in architecture at RMIT University. Michael Spooner is a PhD candidate in the School of Architecture and Design, RMIT University.