PHOTOGRAPHY LAURA BARKER

Overviews of Process, the recent exhibition of drawings and models by Neil Durbach, Alex Popov and Peter Stutchbury at Utopia Art Sydney. The gallery was designed by Robert May.

Peter Stutchbury’s collection of finely worked drawings, three-dimensional sketches, cross-sectional studies and working drawings offer insight into the evolution of his architectural form.

Neil Durbach’s finely made balsa maquettes offer a hint of colour to the exhibition.

Working sketchbooks by Neil Durbach.

Work by Alex Popov. A collection of refined models are displayed in the foreground, with panels beyond. Photographs courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney.

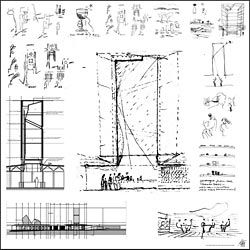

Conceptual pencil sketches and working drawings for Miranda Winery on one of the panels by Alex Popov.

Laura Harding considers Process, a recent exhibition of drawings and models by Neil Durbach, Alex Popov and Peter Stutchbury at Utopia Art Sydney.The title Process does not seem to adequately describe the experimental vitality and intellectual rigour responsible for the collection of drawings and models recently exhibited by Neil Durbach, Alex Popov and Peter Stutchbury at Utopia Art Sydney. “Process” carries with it an unfortunate connotation of procedural determinism – evoking methods of working that are preordained, mechanical and unresponsive. Interpreted in this way, the artefacts in the exhibition are defiantly anti-procedural – revelling instead in the delightful ambiguity and tangential capriciousness that characterize the beginnings of architecture.

Peter Stutchbury presented a collection of finely worked drawings rendered in filigree mechanical pencil lines. The inception of each project is marked by a site study of arresting economy. Generally comprising no more than ten lines and softly blended shading, they form an elegant precis of each place, deftly encapsulating particularities in the modelling of the landscape, the patterning of vegetation or the sinuous geometry of the land/water interface.

A search for clarity in structure and tectonic infuses every subsequent drawing.

Architectural form evolves in numerous plan studies that explore the interplay of programmatic elements within the studied rigour of the structural grid.

Three-dimensional sketches and cross-sectional studies elaborate the tactile and experiential potential of both structure and enclosure. Finely drafted working drawings in the computer-aided hand of Stutchbury’s collaborators are presented with the ubiquitous red “mark-up”, recording a process of review that seeks to eradicate any hint of redundancy. The most skilfully executed projects emerge in built form through this process of refinement completely unfettered, exuding the penetrating clarity and uncompromising directness of the initial esquisse.

Alex Popov presented facsimiles of sketches and working drawings rather than the artefacts themselves – but even this did not undermine the evocative strength of his loose, thick pencil sketches. For Popov, each project stems from seminal studies of an architectonic module. These generative components are not merely structural, but have a strong spatial and formal imperative, anticipating the definition and proportioning of rooms, patterns of usage and circulation, the transmission and rendering of light and methods of occupying a site. Plans begin as ideograms of dots and lines that codify the arrangement of modules and are developed into highly refined spatial sequences of rooms and courtyards, articulated by the rhythmic cadence of their structural bays.

Meticulous models are used for precise testing of proportion, alignment and junction rather than formal exploration.

Form is explored at the scale of the elemental components and manifest in their aggregation and disposition on each site.

Intriguingly, the drawings of his most recent project suggest a shift in working method. The proposal for the Miranda Winery in Victoria is primarily driven by an intuitive response to site and form, rather than a pervading tectonic module.

The scheme has developed from a series of impressionistic studies of the profile of tobacco sheds in the King Valley landscape, neatly recorded by Popov as “Ned Kelly country – mask meets San Gimignano!” The lively drawings of this project betray a strong interest in form – low-profile pavilions skim the ground plane within an armature of sculpted berms and are topped with a series of jaunty lanterns that evoke the picturesque verticality of the sheds.

A playful cast of cartoon wine-tasters inhabit the rooms beneath the lanterns, fervently raising their glasses into the light to assess the clarity and colour of the Miranda red varietals.

Neil Durbach presented a series of working sketchbooks that offered a highly personal and rich assemblage of musings, observations and speculation. Durbach’s drawings are restlessly kinetic. They are worked in waxy coloured leads, fountain pen, ethereal watercolours, biro – whatever is at hand. The effortless pliancy of the practice’s geometry is honed in scores of tiny three-dimensional sketches; detailed planning issues are wrestled with in densely worked diagrams littered with dimensions; Commonwealth Place is whimsically depicted beneath a five dollar note, using its fine etching as an impromptu site elevation. Just when you discern the thread of a project or semblance of method the page erupts, morphing from plan to axonometric, into elevation or section, an alternate project or observational studies of precedents, objects, cartoon characters and human figures. Beautifully drawn studies of faces, folded legs and feet routinely take possession of the page, oblivious to its boundaries and the drawings beneath.

The sketchbooks are accompanied by a collection of exquisite balsa maquettes.

Myriad mutations of recognizable Durbach Block projects are presented, painted in vibrant colours as if to induce a momentary stasis, enabling critique and assessment.

They have a beguiling and infectious energy – you begin to suspect that they are mischievously rearranging themselves on the shelf and transforming into alternative projects each time you turn your back.

Durbach’s drawings and models are compelling in the way that they allude to process by displaying only its vestiges.

They highlight the role of exhaustive, critical intellectual questioning and interrogation in the search for an architectural project. On one of the sketchbooks, in tiny scrawled print, Durbach has recorded an aphorism attributed to Picasso – “To search means nothing in painting. To find is the thing.” The experiential power of House Holman, the Canopy Apartments or the Deepwater Woolshed make it difficult to dispute this as an equally valid observation of architecture.

Durbach, Popov and Stutchbury certainly don’t seek to fetishize process or prioritize the search. The extraordinary depth of their visceral drawing and model-making simply remind us that architecture cannot exist without it. LAURA HARDING IS AN ARCHITECT WITH HILL THALIS ARCHITECTURE + URBAN PROJECTS.