WHAT MIGHT WE LEARN FROM ZOOLOGY? COLIN MARTIN REVIEWS ZOOMORPHIC: NEW ANIMAL ARCHITECTURE, WHICH PROPOSES THAT ANIMAL FORMS AND COMPUTER SOFTWARE TOGETHER OFFER NEW FORMS AND OPPORTUNITIES.

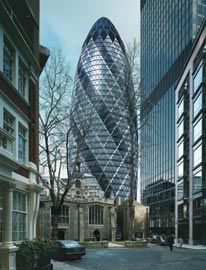

Foster and Partners, Swiss Re Headquarters. London, England, 1997–2004. The appearance, structure and ventilation system bear similarities to sea sponges.

Aerial view of Gregory Burgess Architects’ Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre. Photograph John Gollings.

The exhibition installed at the Victoria and Albert Museum. A row of paired Victorian display cases stretching toward the end wall, on which Gregory Burgess Architects’ model of the Brambuk Living Cultural Centre is displayed.

ZOOMORPHIC, AN EXHIBITION at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, is described by its curator Hugh Aldersey-Williams as “the collision between architecture and biology”. Presenting international examples of how animal morphology has influenced recent architectural forms, Aldersey-Williams argues that contemporary architects are turning to the animal kingdom for inspiration, making use of novel computer software and new materials to design and build more freely. Although he shows examples of buildings based on all major divisions of the animal kingdom, merely identifying such structural similarities doesn’t quite deliver the promise in the exhibition’s premise. His accompanying book is more satisfactory in this regard, enabling us to see the herd rather than the elephants. He argues that writer Philip Steadman’s 1979 assertion that buildings “…are inert physical objects and not organisms; and the relevance of biological ideas to their study can only in the end remain of an analogical and metaphorical nature”, is no longer valid. Aldersey-Williams cites instances of architects who have learnt from animal function as well as being inspired by their forms, and they come across as the more highly evolved practitioners. Foster and Partners’ design for the new, London headquarters of Swiss Re (1997–2004) is one building that fits the bill. Its shape, structure and ventilation scheme are paralleled in the class of sea creatures known as glass sponges (Porifera), which have elongated exoskeletons. They filter nutrients from the water that they suck in at their base before expelling it from a hole at the top. Described by Foster as London’s “first environmentally progressive tall building”, the 40-storey tower has six lightwells or atria spiralling upwards through it, using natural ventilation to circulate air and reduce the building’s dependence on airconditioning, in a similar manner to the feeding mechanism of sea sponges. It functions like the animal whose form it copies.

Overall, though, Zoomorphic is a jumble of animal and architectural objects. Admittedly, the “Contemporary Space” in the nineteenth-century Victoria and Albert Museum building is unpromising: a long, high-ceilinged rectangle, more of a corridor than a room, leading into a rotunda. However, given the curator’s objective of linking architectural design to nature’s elegant forms, it is ironic that exhibition designers Make Communications made such a poor job of it. Here, form certainly doesn’t follow function. Huge museum display cases, pushed end-to-end and shrouded in white fabric, delineate the exhibition area, where a row of backto- back pairs of Victorian display cases stretches toward the end wall. If ever an exhibition deserved a layout that facilitated visitors’ learning, this was it. It was a good idea to borrow skeletons and stuffed zoological specimens from the Natural History Museum across Exhibition Road, in order to compare them with buildings. Cramming them into cases with a selection of architectural models, drawings and photographs, was not. Unless the intention was to parody the bad old days of exhibition display, in which case siting explanatory panels filled with tiny text at knee level, in dim light and therefore practically unreadable, was inspired. Only on entering the rotunda, where large, freestanding models of buildings are more imaginatively lit, is there any relief from stooping low for enlightenment. Here, however, the projection of multiple images onto the black surface of a shallow pool seems a gratuitous special effect. What is its function? Is it meant to represent the primordial pool from which life – animal and architectural – evolved? The curator provided the most amusing line that I’ve encountered on the obligatory panel of acknowledgments: “No animals were harmed during the making of this exhibition.” ›› Australia gets a look-in twice. A photograph of Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House (1957) is displayed without context, however our contribution to the new movement is highlighted in two visitor centres – one in the Grampians National Park in Victoria and another in the Uluru- Kata Tjuta National Park in the Northern Territory. Gregory Burgess Architects developed their designs for both centres in workshops with local Indigenous people and both refer to animal forms that hold meanings for particular Indigenous groups. The undulating corrugated iron roof of Brambuk Living Cultural Centre (1896–1990) evokes the outstretched wings of a cockatoo, a totemic symbol or emblem of kinship for the Koori people. A pity, then, that the closest avian specimen that could be found for display above Burgess’s huge architectural model, which dominates the end wall, was an osprey, its outstretched talons poised to strike at its prey. Not only the wrong species, but also the wrong pose, as Burgess’s design was influenced by behaviour known as “anting”, in which the bird stretches out its wings on the ground so that ants can clean its body. The serpentine form of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre (1990–1995) derives from the creation myth of the Anangu people. The hand gestures that Burgess noticed a woman use, to describe the battle between two snakes, are evoked by snaking lines drawn in red sand on the bottom of the case displaying this project.

Designing buildings capable of adapting to environmental changes is a key goal in the emerging field of biomimetics, defined by pioneer Julian Vincent as “the abstraction of good design from nature”. Biomimetic architects aim at closer integration of form and function, for example in the use of moveable aluminium panels on buildings to mimic the way in which animal fur traps an insulating layer of air. When that approach is further down the track, a future exhibition might demonstrate the benefits of architects learning from animal function as well as observing their form.

COLIN MARTIN IS AN AUSTRALIAN FREELANCE WRITER AND CRITIC BASED IN LONDON.