Timber corona, Cranbrook Tennis Pavilion. Photo Bruce Crosson. Bruce Crosson collection.

Right Wall panels and model showing St Peter’s Cathedral, 1875.

View with model of Hamilton House, 1891.

View with model of Gostwyck Woolshed. 1872.

Large detail built into the fabric of the exhibition.

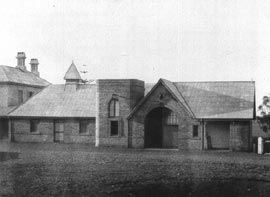

Stables at Baroona, Whittingham, 1890. Photo Cutts Collection, Newcastle Regional Public Library.

In his foreword to the book accompanying the exhibition John Horbury Hunt – Radical Architect 1838-1904, Peter Watts remarks on the relative fame of convict-architect Francis Greenway versus the obscurity of John Horbury Hunt, despite what Watts sees as the obvious difference in quality of the two architects’ work. Greenway’s unexceptional work is overshadowed by the significance accorded him as the first recognised architect in the colony, and his having arrived as a convict. Hunt’s arrival in the colony had nothing of this immediate historical significance attached to it, and the quality of his architecture has not awarded him historical significance within a national story driven by larger themes.

The purpose of the exhibition of Hunt’s work at the Museum of Sydney can be seen, at one level, as an attempt to redress that historical imbalance, or, more specifically, to promote Hunt’s significance in the history of white settlement in New South Wales through the quality of his work, relative to that of his international architectural contemporaries. To the trained eye, it does seem remarkable that such a body of work was produced in New South Wales in the second half of the nineteenth century. The exhibition should promote further serious consideration of how such a progressive architecture flourished in the colony without any hint of it occurring (as we are so often told to understand) as a mere after-effect of the dissemination of taste from the imperial centre.

To the untrained eye, however – precisely the eye that the exhibition wants to attract – these issues become problematic. How might an exhibition communicate not just the documentary fact of this architecture’s existence for the historical record, but something of its professed “radicality”?

The great success of the exhibition comes with a “multimedia” approach to the communication of the architecture; an approach that allows different media to present, by analogy, the meticulous craft of Hunt’s architecture. The Museum of Sydney teamed up with students from the Faculty of the Built Environment at the University of New South Wales to produce a series of wooden models and computer visualisations of selected projects. The models, in bass and balsa, have been made with a careful attention to detail. They do not attempt to represent the materiality of the buildings, but something of their general massing and, in some instances, the schema of ornamentation. In their abstraction, the craft of the models gives an account of the craft of the buildings. In a related way, the visual tactility of the computer visualisations operate as an analogy of the material tactility of the architecture, and several of the visualisations are able to present explicitly how a particular building comes together structurally. Several examples of Hunt’s original drawings and specifications are also displayed and their layers of annotations speak of the transactions between architect and builder. Unlike the models and visualisations, these drawings are a trace of the collaboration that produced the architecture. Literally written on from all sides, we can read these documents as collaborative traces before we might read them as architectural blueprints.

The visual boards which contain archival photographs of the buildings, and which give text descriptions of all the projects shown, suffer in comparison with the visualisations, drawings and models. The text, partly by default, obscures the structural innovation and craft basis of the architecture in a veil of overtly technical language. We can be impressed by the way in which, for example, at the Cranbrook Tennis Pavilion of 1875, “the octagonal corona is a triumph of the carpenter’s skill.

The arched braces, securely trussing every second rafter, meet above an octagonal metal plate fitted to the downward extension of the apex finial.” But can the untrained reader understand why such a construction solution is architecturally significant?

Viewing the model of the same building, we can at least empathise with the skill with which it is crafted, its particular attention to detail that is present before us, and thereby imagine an architecture of such finesse.

At base, I think it is a recognition of the sense of craft and materials in the architecture that might form the basis for a wider appreciation of Horbury Hunt’s work – given that this wider appreciation means an appreciation by non-specialist viewers. The involvement of students in an institutional collaboration has made this wider appeal possible, and the location of the exhibition within the Museum of Sydney has meant that it has a good chance of attracting a broader audience, and one used to engaging with the innovative display techniques for which the museum is well-known.

Photographer: Brett Boardman

Source

Discussion

Published online: 30 Aug 2012

Words:

Charles Rice

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2002