Review

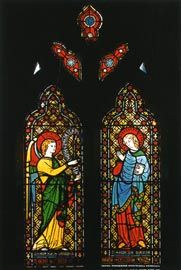

Annunciation window (1847), St. Joseph’s Church, Hobart. This Hardman stained glass was given to Bishop Willson by Pugin and includes the inscription: “Pray for the good estate of Augustus Welby de Pugin”. Photo Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

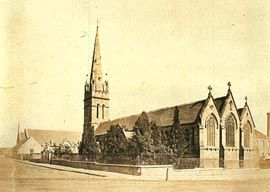

St. Benedict’s Church (1845- 56), Broadway, Sydney, before alteration. The largest completed Pugin church in Australia, it was sadly shortened and mutilated during reconstruction to allow for the widening of Broadway in the 1940s. Photo Cambridge University Library, Royal Commonwealth Society Collection.

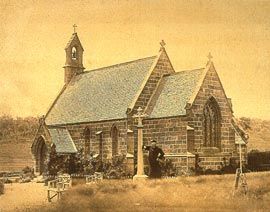

St. Paul’s Church (1851), Oatlands, Tasmania. A fine example of Pugin’s simplest idiom for modest parishes, built under the supervision of convict architect Frederick Thomas, after an 1843 Pugin scale model. Photo Archdiocese of Hobart Museum and Archives.

Silver chalice (1847), for wine of eucharist, made to Pugin’s design from a melteddown classical chalice presented to Bishop Willson by Pope Pius IX.

Silver pyx (c.1841-43), for consecrated bread, decorated with wheat and vine motifs, symbolic of bread and wine of the eucharist. Made by Hardman. Photos Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

Until recently, few people knew that the great English Gothic revival architect and designer A. W. N. Pugin produced work specifically designed for the Antipodes, though buildings in the Puginian idiom by Edmund Blacket and William Wilkinson Wardell are well-known. This fine exhibition and superb catalogue by Brian Andrews, continuing research presented in his Australian Gothic, finally establishes the extent of Pugin’s direct impact on Australia, principally through the Roman Catholic Church in Tasmania and New South Wales.

Andrews explores the patronage of Pugin’s close friend Robert Willson, who built Pugin’s celebrated St Barnabas, Nottingham, and became the first Catholic Bishop in Hobart Town, and of Sydney’s Archbishop Polding. Bishop Willson was the brother of E. J. Willson, who collaborated with Pugin’s father on several important books of Gothic details, and who was as enthusiastic supporter of “Christian architecture” as Pugin himself.

The exhibition has been produced by the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and it opened in Hobart on the 150th anniversary of the night of Pugin’s death.

Pugin died insane at the age of 40, having produced over a

hundred buildings and thousands of designs for unbuilt projects, furniture, metalwork, stained glass, ceramic tiles, wallpaper, textiles, jewellery and book illustration, as well as having written and illustrated thirteen books, notably the influential Constrasts (1836 and 1841) and The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841). He transformed architecture and design in England, forming the starting point for High Victorian Gothic as well as William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement, and he had considerable influence in mainland Europe. The impact of his theoretical writings extends into the twentieth century and can still be discerned today.

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812- 52) was an astonishing, tragic, but thoroughly engaging fanatical genius.

Brought up and educated at home by his eccentric antiquarian father and radical forceful mother, he knew as much as anyone in England about Gothic construction when, by the age of fifteen, he designed furniture for the refurbishment of Windsor Castle and silver plate for the Royal Goldsmiths. In his late teens he was a scenery designer for West End theatres, including Covent Garden, ran a interior furnishing business and was bankrupted, was briefly imprisoned for debt, and was shipwrecked and nearly drowned in his own boat off the coast of Scotland. By 1832, at the age of twenty, he had been married and widowed, leaving him with no money and a baby daughter, and by the following year both his parents were dead. This life crisis and a small legacy from an aunt apparently provided the impetus for his subsequent independent practice (supported by his later wives and family) which was fanatically devoted to the revival of Gothic architecture and design, in the service of the remaking of a Christian Catholic society.

Enthusiastic, talkative, completely unpretentious and often dressed in a working sailor’s clothes, Pugin seems to have been a most likable character. “There is nothing worth living for but christian architecture and a boat”, he once announced. He maintained a 30 ton lugger which he used to rescue shipwrecked sailors off the coast within sight of his home on the cliffs at Ramsgate, while also supplementing his income with salvage operations. On his European travels he took minimal luggage and carried his essential equipment in his capacious pockets, so that he was always ready to sketch some medieval detail – perhaps the inspiration for Australian architect Horbury Hunt’s similar dress habits. Pugin practised largely on his own, often singing while he worked, in his house at Ramsgate, with the help of his third wife and, from 1845, his one male pupil, John Hardman Powell, the nephew of his friend, the metal and glass manufacturer John Hardman.

Through Archbishop Polding and Bishop Willson, Pugin’s

determination to promote Gothic as the only style that was a true representation of Christian values extended to the Antipodes, much to Pugin’s expressed delight. Bishop Willson took with him to Tasmania a collection of Pugin-designed artefacts, many of simple design to suit limited funds, to form the basis of a Catholic see entirely modelled on medieval English precedent – a new “Gothic Paradise at the Antipodes”. This included vestments, cheap church texts with Pugin illustrations for convict use, a bishop’s throne, metalwork, a stained glass window, full-size exemplars of stone crosses, piscinas, a font and even gravestones, and three detailed models of simple church designs that could be easily copied by local builders with limited skills.

These models were the basis of the new churches of Oatlands (1851) and Colebrook, (1857) and additions to Richmond church (1859). Willson also encouraged a young local designer, Henry Hunter, to become a Puginian architect, using Pugin’s publications as a guide.

Sydney’s Archbishop Polding also commissioned designs for vestments, metalwork and seven church buildings – St.

Stephen, Brisbane (1850), St. Francis Xavier, Berrima (1851), St. Augustine of Hippo, Balmain (1851), St. Benedict, Broadway (1856), St. Charles Borromeo, Ryde (1857), St. Patrick, Parramatta (1859) and, surprisingly, the second St. Mary’s Catholic Cathedral and School, Sydney (1843-1865, but never finished and now replaced by Wardell’s cathedral).

Thus, examples of Pugin’s architectural work, as well as his books and church fittings, were present in Australia, as models of correct Gothic work, alongside the early efforts of Edmund Blacket, themselves based partially on Pugin publications. The great Pugin follower William Wardell then arrived in 1858 to take up the mantle of Puginian Gothic, culminating in his celebrated Melbourne Catholic Cathedral (1858-1938).

The exhibition carefully traces the two stories of Pugin patronage in Tasmania and New South Wales. The display is dominated by Pugin’s fine church plate and remnants of his sets of vestments, but it also includes his publications, full-size facsimiles of his exemplar stonework, large reproductions of his two Tasmanian stained glass windows, brass rubbings, and architectural drawings, early photographs and recent views of his buildings. A set of working drawings for a church in Guernsey, acquired by Bishop Polding but never used, shows Pugin’s extraordinary shorthand drafting, where few lines connect, clearly carried out with terrifying rapidity, but with his usual sure sense of proportion and detail.

The exhibition is arranged with loving care and thought, beginning with general background on Pugin’s key ideas, publications and buildings – principally St.

Giles, Cheadle (1841-46), his own house and church at Ramsgate (1843-52) and of course his great Houses of Parliament (1835- 52), designed in association with Charles Barry. It also includes an excellent short video on Pugin and his ideas and three vivid extracts from his diary and letters as a gentle voice-over in a later section of the exhibition.

The lavish catalogue, with every exhibit illustrated in colour, is an impeccably edited, beautifully produced work that is a major contribution to Pugin scholarship. Rosemary Hill, who is completing a new biography of Pugin, has contributed an excellent introductory essay, which must be the best short introduction to Pugin’s life and times available. Brian Andrews’ extensive, meticulous essays and catalogue entries (plus three by English Pugin scholar Alexandra Wedgwood) are a mine of fascinating material. Especially revealing of Pugin and Willson’s fervour is the story of how, when the Pope in Rome presented Willson with a chalice of classical design, Willson promptly had it melted down and reformed into a gothic chalice, designed by Pugin and made by his friend and associate John Hardman.

The lineage of Pugin’s principles of truthful design responding appropriately to function, and his emphasis on reform of society through design has been frequently traced through the Arts and Crafts Movement to early modernism. Pugin’s emphasis on the architectural expression of the functional parts of a building was explored by Le Corbusier and is still a much-used and valid method of deriving form. What the exhibition demonstrates most movingly is the completeness of Pugin’s vision of a Christian society where the form of every artefact relates closely to its function and every decorative detail has a meaning. This is most poignantly illustrated by a little pyx to hold consecrated bread, decorated with intertwining wheat ears and vine leaves, symbolising bread and wine, the body and blood of Christ. Many people today may not identify with the Christian message, but we would do well to take note of the ethical purpose and search for human and spiritual meaning in the things that we design, make and use, which challenges the current pursuit of the novel or fashionable image.

The exhibition is at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery until 10 November. It then tours to Bendigo Art Gallery, 14 December–26 January 2003, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 14 February–18 May, and Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, 5 June–20 July.

Bibliography

Brian Andrews, Creating a Gothic Paradise: Pugin at the Antipodes (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 2002).

Brian Andrews, Australian Gothic (The Miegunyah Press, 2001).

Paul Atterbury & Clive Wainwright, Pugin: A Gothic Passion (Yale University Press, 1994).

Alexandra Wedgwood, ed. “Pugin in his Home”, a memoir by J.H. Powell. Architectural History, vol.31, 1988, pp. 171-205.

Phoebe Stanton, Pugin (Thames & Hudson, 1971).