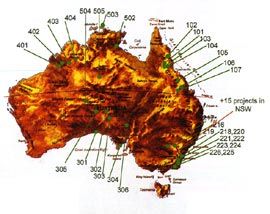

Map demonstrating the spread of work currently undertaken under the Housing for Health and Fixing Houses for Better Health programs.

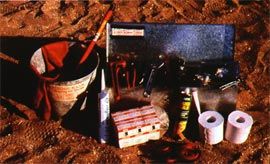

The tool kit used by the Aboriginal Survey Fix teams.

A local community survey fix worker completes the installation of a new shower rose. The plastic tube around the hat is to test that all floor wastes function well.

The day to day living environment can have a major impact on people’s health. One hundred and fifty years of public health knowledge has shown that when key parts of that living environment – such as water, washing facilities and the efficient removal of waste water – are either not present or not working, health suffers. The living environments of many Australian Aboriginal people rarely provide basic working facilities of this kind. However, although the resulting poor health has been widely documented, with data collected on Aboriginal people to “prove need” over the last 30 years, rarely has anything been done about the problems found.

Housing for Health programs are changing this pattern of documentation, ensuring that immediate improvement goes hand in hand with the careful documentation of short and long term needs What started as a small public and environmental health review in Central Australia in the mid 1980s, has now expanded to a modest national program that aims to “stop people getting sick” by making basic, low-cost improvements to existing housing and immediate surrounding living areas.

The program began in 1986 when Nganampa Health Council, an Aboriginal controlled health service in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands, completed an environmental and public health review that set out some simple principles to improve the health of Aboriginal people in the north-west of South Australia by reducing infectious disease, particularly in children up to five years of age. These principles became known as “Healthy Living Practices”, and they all required functioning “health hardware”. (Health hardware is any part of the living environment that contributes a health benefit, for example hot water system, tap, tub, drain, stove and so on). In order of priority, the Healthy Living Practices are: safety issues that may threaten life (electrical, gas and structural safety); the ability to wash, particularly children; the washing of clothes and bedding; removing waste water safely; improving nutrition; reducing crowding; reducing negative contact between animals, insects, vermin and people; reducing dust; improving temperature control of the living environment; reducing minor injuries.

Housing for Health: Towards a better living environment for Aboriginal Australia, published by Healthabitat in 1994, documented a project in the small community of Pipalyatjara. This work aimed to define a set of standard, repeatable tests to assess the health and safety function of the house and surrounding yard area; to define what resources were need to keep community houses fully functioning for one year; to document clearly why houses fail and the detail the costs involved in all maintenance; and to assess to what extent the local community were able to be involved as participants in the housing assessment and fix work. Most importantly, the work showed a clear link between improvements in the living environment and key aspects of health.

The success of Housing for Health resulted in similar pilot projects in Queensland and New South Wales. During 1999 the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC, the national peak indigenous representative body), in consultation with the federal housing department, accepted a proposal by Healthabitat to assess and fix 1000 houses nationally. This project, the national “Fixing Houses for Better Health” project commenced during 2000/01. It was designed and managed by Healthabitat using the accepted “Housing for Health” process. Area managers carried out the day to day running of the projects in the five participating states and the dedication and effort of these managers to ensure the success of the project can not be overstated. Following initial approval by the ATSIC Board of Commissioners and the Federal Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, the project has been assisted and managed by state offices of ATSIC and the state and territory Indigenous housing agencies (in Queensland the work was carried out through regional housing organisations). The total project budget to improve the health and safety of 1000 existing houses in rural and remote regions of five states of Australia was $3.65m.

Well over 80% of this budget was spent on directly improving living environment, not on reports or meetings. Repair works on each house started within hours of the project’s commencement in each community. Following Dr Fred Hollows’s principle of “no survey without service”, the Aboriginal Survey Fix teams enter each house equipped not only with a survey assessment sheet, but also a tool box and spare parts. Each member of the team is trained and encouraged to do minor fix works immediately. Within hours of the Aboriginal Survey Fix team leaving the house, licensed trades people (forty nationally) would complete additional works requiring specialised skills.

The preliminary results are as follows: As at March 2002, 792 houses, in 4 states and in 21 communities, have been assessed. NSW, the only state not to have finished the process, has begun work on an additional 105 houses. Over 250 local community Aboriginal staff (nationally, an average of over 75% of all staff) have been employed to carry out the project. They have worked on house assessment, fix works, data entry, and liaison with trades and householders. Over 12,000 items within the living environment have been fixed by licensed trades (mainly plumbers and electricians). This is from a total of over 14,500 jobs identified by the assessment teams to be inspected by the trades.

The main reason identified by the trades for work being required was routine maintenance – an overwhelmingly 60%. Repair of works identified by licensed trades as faulty (or poorly installed) accounted for 22% of the work, while items identified requiring works larger than the project budget (an approximate average of $3000 per house maximum) or not needing work accounted for 15%.Work required due to vandalism, damage, overuse or misuse accounted for less than 3% of works completed. This is particularly important. It confirms similar figures over the last 17 years and provides hard evidence to contradict the popular opinion that the main “problem” in Aboriginal housing are those using the house.

At the beginning of the project, many of the 792 houses were in a poor state. Only 13% (102 houses) had a fully safe electrical system, 33% (261 houses) had a working shower, 52% (411 houses) had a working toilet, 11% (87 houses) had all waste drains working and only 1% (8 houses) had the ability to store, prepare and cook a meal. At the current stage of the project, with 777 houses completed, comparative conditions are as follows: 64% (497 houses) have safe electrical systems, 74% (574 houses) have a working shower, 78% (606 houses) have a working toilet, 19% (147 houses) have all waste drains working, 5% (40 houses) have the ability to store, prepare and cook a meal.

Work lists of all other works not able to be completed within the limited budget ($3000 per house) have been left with each participating community. Common faults identified in houses throughout the project have been documented and forwarded to the review of the National Indigenous Housing Guide to help improve the design of new buildings or major renovations and not repeat the same design or construction mistakes of the last 30 years.

With support from a wide range of participants, Housing for Health projects will continue to improve the most basic parts of the living environment and a chance of improved health. From what is learnt from the detail of the projects it is hoped that better design and construction can follow. Seventeen years of work have shown that it is poorly built and designed houses that are the problem, NOT Aboriginal people. Positive change is possible and it can happen today.

Paul Pholeros is an architect and director of Healthabitat, the other directors are Dr Paul Torzillo, thoracic physician, and Stephan Rainow, anthropologist and public and environmental health specialist. Healthabitat would like to thank ATSIC and the State and Territory Indigenous housing agencies, the area managers of each project, the licensed trades and Aboriginal field workers, and perhaps most importantly the 4000 residents of the houses that assisted with the project. They hope that the gains made through this work can be continued.