Daytime view with screens open, enabling cross-axial views and movement between courtyard and garden. Image: Robert Colvin

Detail of the patterned boards of the screens. Image: Robert Colvin

Old weatherboards from which the pattern was derived. Image: Robert Colvin

Detail showing the way the existing roof is framed and “curated” by the new roofline. The pattern of the screens is a “ripple down” of this cornice line. Image: Robert Colvin

Looking into the living area from the courtyard. Image: Robert Colvin

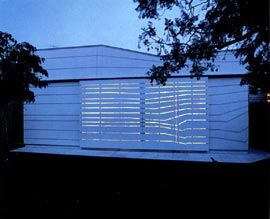

Views of the west elevation in different configurations. Image: Robert Colvin

The courtyard seen from the living area. Image: Robert Colvin

Looking from the kitchen, through the living areas to the backyard, and into the courtyard. Image: Robert Colvin

Alberti thought that it is a requirement for architects to be intellectuals, but I tend to disagree. It is possible, and perhaps even desirable, for architects to shut up and build decently, drawing on the overwhelming knowledge that we already have about architecture. At the same time, I value, as we all do, those architects who manage to engage the task of building with a world of concepts and to prompt discourse in and beyond the discipline. But the intellectuality of architecture is not an issue of comportment as Alberti thought. It is not a matter of talking and drawing in some brainy way – there actually has to be something for the building and the architect to say.

In his kitchen and living room extension for the Negri Callcott family in Brunswick, Melbourne, Shane Murray runs some of these risks. Here Murray opens some big topics for consideration, some of which he has explored in competition entries for major public buildings and in his research at RMIT University. So the question arises as to whether it is hubris to develop these concepts in this modest extension and, following that, whether he gets away with it, whether in the end there is something to be said here.

The programme is a familiar one. A modest early twentieth-century house, not wonderfully distinguished or well built, needed sorting out for a family with young children and the elaborate kit of modern life and hospitality. The plan of the old house was able to be reorganized by removing the kitchen and main living spaces to a new extension at the rear. Murray uses a strategy, which he has developed in earlier designs, such as the Cliff Residence in Parkville (1996), of using a bite-sized court to the north to increase the perimeter of the building and gain daylight. Murray has called the project a “pavilion” because the living room volume is set across this court from the house and linked by a linear kitchen. But spatially, the building does not seem to be an ensemble of pavilion and link but a whole volume, like a bubble drawn to attach itself to the house through a meniscus zone which, more prosaically, is a poché space for a laundry and storage. It is almost as if surface tension might at any moment displace the court by causing the walls to push out in an attempt to minimize the perimeter. This sense of wholeness is partly produced by the amorphous plan-form, which is basically orthogonal but constantly adjusted for local advantage. And this “wholeness” is reinforced by most striking thing about the building – its “board” patterned exterior cladding. Because Murray has patterned the shade screens in a form derived from the cladding, this surface seems all-encompassing, taut, and also large. With the screens shut the patterned surface is larger in area than any other element of the old house, and indeed larger than one would expect in any building of this size. This overall-ness of the formal condition not only avoids under-scaling in relation to the old house (which might have resulted from the kind of mindless over-articulation of much contemporary architecture), it also gives the building a kind of localized monumentality.

I think that this is a very fine work for the reasons implicit in my description: it is aesthetically pleasing and in a way that makes one’s aesthetic pleasure seamless with everyday life. Even the most inventive and challenging aspects of the building’s formal condition are eventually within the sensuous and logical circuit that I claimed earlier is sufficient condition for architecture, even great architecture. But the Negri Callcott house is actually about something else as well. The house is a speculation on the conditions of form in building technology, and how new technologies challenge existing tenets of form and our understanding of architecture at a general level. The question we must consider is if this is not a pretentious claim to intellectual seriousness on Murray’s part.

This issue is raised by the exterior cladding of the extension, which is fibre cement fixed between shadow lines of aluminum channel. What I wrote above about the aesthetic role of this surface would be equally true with any pattern – say geometric, or floral – at the same scale. Murray’s design of this skin is pleasing when considered as a pattern. It has a contemporary sensibility and is a bit like what Paul Smith (and numerous imitators) did in hyper-saturating the striped shirt. But this is the point: the skin is not only patterned it has clear references. The walls resemble weatherboard, but cut in irregular widths so as to look even more archaic, as if these lapped boards were sawn from un-squared logs. The logic of doing this is a kind of tongue-in-cheek contextualism. By apparently following the planners’ exhortations to “fit in” in suburbs of established “character”, but by doing so in a maniacal manner with the exaggerated weatherboards, Murray helps demonstrate the foolishness of concepts of contextualism becoming actual regulations of building form. There is no sarcasm in this, but a degree of worn love for the suburbs. The board effect does, at a certain level, make the building belong with its neighbours, even as it distances itself from them. The waving irregular pattern of the boarding is a ripple downward of the cornice line. While from some places this looks as if it is shaped arbitrarily, it is in fact view specific and acts to edit and curate one’s view of the roof of the old house and the roofs of the neighbours from specific view-points. Here, clearly, the house is leaving the terrain of hand/eye/marble bench-top. Murray pitches the house into conversation with Edmond and Corrigan, ARM, Lyons and others working out how to keep the fire under the bubbling stew of formalist anti-aestheticism and poke-in-the-eye contextualism that has nourished Melbourne’s claim to have its own intellectual discourse in and on architecture.

However, the logic of reference in the boards that I have traced is not the important point of them. The point is that they could be made. The complexity of the boards and the unique shape of each of them is of course not caused by the shape of tree trunks, they are cut from uniform sheets of an artificial material which has no predefined shape property, and, what is more, Murray has had them fixed without laps so that each must be precisely fitted to the next. This has the appearance of conspicuous expense in labour and craft, but it is not. The boards were designed to be precut in the factory from CAD files with only marginally more wastage and complexity of assembly on site than if they were regular Hardiplanks. Murray is setting out to demonstrate that one of the fundamental coordinates of architectural form, that is modularity, is loosing its importance with advances in building technology, particularly the coordination of construction drawings with computer controlled sheet cutting.1 One way to do a very short history of western architecture since the Renaissance would be to say that it begins with the imposition of geometry on amorphous materials and moves through the gradual modularization of bricks and beams, accelerating rapidly in the mid twentieth century with panel construction. Hitchcock and Johnson, when explaining the apparently low-tuned formal characteristics of Modernist building, claimed that Modern buildings could be irregular and tend to the a-formal because symmetry and metre had so thoroughly imbued the components of the building. So, for much of the latter twentieth century the economical use of standard sizes of fibro, plywood or precast concrete provided one of the fixed coordinates of formal invention in architecture.We see this still in ARM’s facade for Storey Hall or Lab’s Federation Square where the problem and the game is how to generate complexity from standard panels, but panels which, these days, perhaps lack a pressing need to be standardized.

What Murray asks is not the simple question of what new fun might be had, or what economies might be possible with cheap custom sheeting. His question is rather what |do we do now that one nicely logical authority for making form has collapsed? And was it needed anyway? Was modularity, like canons of style, or tenets of functionalism, ever more than an attempt to defer the question of what form is? The Negri Callcott house asks the hard questions of whether architects make form or receive and organize it, and where the authority for form lies.

Most architects do not worry about form and its relations to the architectural object – assuming that form is what results from their activity, and that they have the weight of precedent behind them to think this. After all society is generally accepting of what we claim we do.We might call this a naively naturalist account of form and it is a perfectly reasonable way to make architecture as far as I am concerned. But there is abroad a noisome intellectualizing of this formal naturalism. Particularly when accounting for their houses, some architects are prone to a religiose anthropology of dwelling, wherein they claim to be uniquely privileged to actualize what people really want and need. Form, for such priestly architects, can only ever be the name of a problem – a failed reciprocation of people and place, where architecture suddenly becomes uncomfortably visible instead of sublated in experience. But what would architecture be without this necessary failure? A naturalist account of architecture has no means to distinguish human building from |the architecture of animals and insects. Architecture, in such a theory, would be just the mucus that holds the sticks together around the wasp’s nest.

In the Negri Callcott pavilion much of the “design” is a modest attempt to give |shape and legibility to everyday human activity. But the relatively arbitrary form of the boards and the highly etiolated references by which Murray seeks an authority for them, and then questions his own need to do so, are a claim to practice architecture not only intelligently, but in a manner that opens the discipline to the general intellectual discourse on culture and cultural values, as Alberti claimed we should. What allows us to forgive the ambition of this is that Murray asks questions rather than reading us the answers. The Negri Callcott pavilion is a bright light exposing the myth of a natural authority for architectural form to a level of justified anxiety.

1. In checking the facts for this article with Murray, it turns out that this story is not as neat as I tell it here. The builder found it cheaper to have an apprentice cut the sheets by hand on site than to go through the CAD-CAM process, but you get the general idea…

Credits

- Project

- Negri Callcott Pavilion

- Architect

-

Shane Murray Architect

- Project Team

- Shen Murray, Paulo Sampaio, Charina Coronado

- Consultants

-

Builder

A. J. Hewitt Construction

Quantity surveyor Construction Planning and Economics

Structural consultant Felicetti

- Site Details

-

Location

Brunswick,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses