|

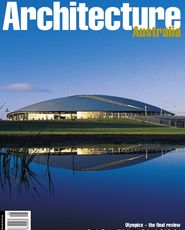

Above left The dynamic juncture of the curved roof edge and the undulating baltic pine race track. Centre The eastern corner of the transparent foyer “prow”, sheltering under the extended roof. Entry to underground parking is to the right. Right Aerial view from the north, showing the siting of the low, sleek form in suburban Bankstown. Originally designed for the site now occupied by the tennis centre, the velodrome was one of the earliest Olympic buildings to be contracted. Indeed, it pre-dates the actual awarding of the Games to Sydney. If it was not a template for the imagery of arching steel that characterises the Olympics, it certainly set the tone. Resolving the final shape, and even the location, was more complex than for any other Olympic arena, but the process does not appear to have unduly distorted the monumental airship now at rest in the suburban Bankstown landscape. The sleek, shiny roof floats above an oval cycling track, its geometry reminiscent of racing aerodynamics. But Euclidean forms, even stretched and flattened ones, are also a reminder of the ideals - classical and humanistic - embedded in Olympic culture. In Barcelona, the most metaphoric arena was the velodrome by Esteban Bonell and Francesc Rius - a building which combined new and old elements with, in the words of architectural historian William Curtis, “the straightforwardness of a bicycle wheel”. (Likewise, Olympic publicity material unfailingly compares the Dunc Gray Velodrome to a cyclists helmet.) The Sydney velodrome shared engineering consultants (Ove Arup & Partners) with other notable recent examples - the slick and expensive Berlin velodrome designed by Dominique Perrault and the facilities packaged with the Manchester and Johannesburg Olympic bids. But if a ratio exists between budget and structural achievement, it is in Sydney’s favour. The Dunc Gray is the first single-layer metal shell building in Australia, and the world’s first such shell constructed without the formwork or falsework needed for conventional dome construction. This meant internal work could continue unhindered at ground level while the support trusses were craned and bolted. In the externally similar Manchester velodrome, a long central spine truss supports a series of semi-suspended arches. This system was costed for Sydney, but proved uneconomical. At an early stage a parallel arch structure (like the Adelaide “armadillo” velodrome) was also considered, and the original published perspectives show “butterfly” trusses encompassing a curved cable net roof form. Over subsequent stages of development and relocation this has been smoothed and compacted into a turtle-shell skin of Zincalume stretched over an 100:150 ovoid plan. One problem inherent in this form is the suction created by wind scooping over. This was solved by anchoring the roof with a formidable ring beam, supported along its wavy course by V-columns. The superficial effect is of a straightened version of the dome at the centre of the 1951 Festival of Britain. The internal experience is dynamic and contemporary. This is accentuated by the convergence of the waving roof edge with the undulating Baltic pine ribbon of the track, and by arching light diffusers overhead. The structure evolved in an extraordinary collaboration between architect and engineers. It is an epic history, lasting nine years in which everything about the project changed but the architect. In December 1991 Paul Ryder and Paula Valsamis won the competition for a site at Homebush Bay. Their design was developed in the delicate period between the Games bid and the formation of SOCOG. The Department of Sport and Recreation, owners of the proposed site, assumed the role of client. To facilitate detailed design and tendering documentation, Ryder Associates combined with a larger firm, SJPH.

In 1993 the Olympic Coordination Authority took control. Previously, the clients had themselves been architects: the Bid architectural consultant and the DSR staff. In contrast, the OCA was a culture of managers seconded from the construction industry with essentially pragmatic project management goals. The ethos and budget changed, resulting in rationalisation of the program. This was a difficult phase, marked by contractual tensions. It took 18 months for function, client and project management to be re-aligned. The job was returned to the Department of Sport and Recreation, and expressions of interest taken for BOOT schemes, which secured funds for all the major Olympic constructions. The 1996 Urban Masterplan meant a change in site. The velodrome had been considered integral to the trio of major works grouped at the western end of the precinct, but with the development of an indoor multipurpose arena this was reconsidered. Design development continued, but for an unknown site and context. Next, property management conflicts at Homebush Bay knocked the project off the precinct completely. The entire project was re-commissioned, with design concept work beginning once again, for a suburban site in an environment of big-tree regeneration and bush edges. In the final stage, training functions were added make the building a general sports and events facility. Sporting imagery was toned down to achieve the required “civic centre” look. All wall-suspended elements were pushed out to the exterior. Exit points were packaged in radiating “pods” of 850 mm ceiling plate that accentuate the building’s scale. Internally, the concourse design was amended to accommodate temporary event seating. The glazing and facade were reworked to respond to the scale of the surroundings, with external flourish concentrated in the large transparent prow of the main foyer. The shift to the suburbs also meant a lower, flatter profile. To secure stiffness at this gradient of curvature a kind of eggshell integrity has been achieved by triangulating the structural matrix. The load is just under 45 kg/m2. (By comparison, the canopy at Melbourne’s Colonial Stadium is 100 kg/m2.) At this stage, lighting and operational energy use requirements were also increased. Despite these late changes, ESD achievements have been on par with the best of the Olympic projects: roofwater retention, even and sufficient natural lighting and natural ventilation, with no air conditioning required. Throughout the stages of redesign and relocation adherence to idiomatic form has been controlled to amplify a feeling of space and environmental fit. In aerial photos the monumental roundness seems to focus surrounding urban movement patterns. Formal strategies are significant because the scale of the Olympic project has militated against technical finesse in many discrete works. In the case of the velodrome, a more generous budget might have permitted a streamlined roof weighing a sheer 15 kg/m2. In contrast, the architect’s dissatisfaction with the quality of some finishes has, so far, led him to withhold the building from award assessment. At the time of the original commission there had been little in Olympic history to use as a yardstick. Moreover, the strictures of Sydney’s Olympic brief, budget and project management have been formidable limitations to design. The substantial achievements of the Dunc Gray Velodrome have been hard-won. |

|

||||||||||||

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2000

Words:

Ian Perlman

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2000

Looking north towards the main entrance. The free span, single-layer, shell roof floats over the race track.

Looking north towards the main entrance. The free span, single-layer, shell roof floats over the race track.

Plan of the spectator concourse.

Plan of the spectator concourse.