|

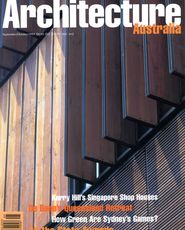

top Front (south-west) facade on Bulkit Timah Road. above Model of the south-west/north-east section.

More photos can be found in the version! | Photography Albert Lim Review Leon van Schaik Not surprisingly, intellectuals in Singapore make much of the difficulty of creating a design culture in a risk-minimising political community. Outside observers, like Rem Koolhaas, suggest that the locus of creativity in this community resides where risk is allowed: in the manipulation of global investment and in the facilities created to serve commodity flows that have made Singapore into a financial centre equivalent in its region to, for example, Paris’ role in the European Community. Certainly Singapore’s business leaders have demonstrated a lemming-like agreement to implement a building procurement strategy that Professor JL Cohen likened (in an address to the Artpolis Symposium in Kumamoto, November 1996) to a ‘museum-zoo’ approach to city design: a KPF here, a Foster there … Sadly too, in a decline from the early days of open competition that enabled some local architects to construct some remarkably ambitious buildings, the government now seems to be set upon the same self-defeating procurement strategy. This is not how to develop an exportable design culture. Nevertheless, a stratum of design ambition persists, and Singapore boasts a small number of architects who are doing work that could well be so exported, were it to be properly celebrated and supported. Amongst the emerging ‘stars’ are Tang Guan Bee, Mok Wei Wei and Richard Ho; and it is a sign of our isolation and Singapore’s own lack of confidence that we don’t know their work well already. But before Australians become patronising about this state of affairs, we would do well to consider the museum-zoo mentality that pervades commissioning bodies for major art galleries in Sydney and Melbourne, and our general propensity to follow Singapore’s architectural lead in the corporate sector: here a Renzo Piano, there (it is rumoured) a Jean Nouvel … An encouraging aspect of our relationship with Singapore is the fact that Perth-educated Kerry Hill has based his regional practice in Singapore, with a more recent outpost back in Fremantle. Kerry Hill aligns himself with a group of architects employing a neo-modern approach to the explosive growth of Asian cities. While a hill-top house by Tang Guan Bee dexterously out-expresses the tide of wealth displayed below, a house by Mok Wei Wei turns its back in immaculately modern terms on the tide of Bangkok Baroque suburbia engulfing West Singapore; and Richard Ho’s Cicada Gallery is a masterpiece of understatement. Kerry Hill’s new project—a five storey shop/office/apartment building called Genesis on Bukah Timah Road—shines out of the sub-corporate image-making fog of the fringe of downtown—a beacon of architectural care that is in startling contrast to its neighbours. This building has simple but important aims. It sets out to demonstrate that a sound financial investment can be made on a small site; that shops and houses and offices can continue to coexist in the inner city, and that a multi-storey block can use tropical timbers and be climate-responsive and naturally ventilated. Hill’s building honours its antecedents in the family of shophouse designs, from colonial shutters to William Lim’s building-scale timber screens. There is also the same respect for context that Tan Hock Beng noted (A+U February 97) of Hill’s better known work: the restrained yet voluptuous resorts. Recently Hill’s office has become obsessed with the problem of the house, and some solutions to really tight planning have been incorporated into Genesis. The building provides four apartments above two floors of office space and a showroom. As described by the architect, “the box form of the building is the result of statutory height limits and boundary setback requirements. A finely detailed timber screen set within a steel frame provides sun protection and visual privacy.” He notes that “the building has urban connotations for Singapore in that it replaces four traditional shophouses in which you live above your place of work.” This continuity is important to him. “The allowable plot ratio has doubled the previous gross floor area of the shophouses; however, the proportion of residential to commercial area remains the same. Within our design, the narrow vertical spaces of the shophouse are replaced by horizontal layers punctured by light wells where courtyards previously existed.” This is a transformation that works qualitatively as well as analogically. He says that the practice likes to think of the building as a contemporary shophouse; that it demonstrates that the old model of unity of living and working is still possible in today’s spatial expectations. As with the “long life, loose fit” shophouse, Hill claims a modest budget and a “very price-competitive” outcome. All of this I corroborated on a visit to the building—which provides pleasure through an almost mathematical principle of parsimony, through understatement, careful manipulation of proportion, exquisite modulation of different sized grilles and screens, resolved detailing and well-controlled construction, and half-visible shifts in the glazing planes and the creation of mediating spaces between the street and the glazed facade. Certainly the planning is exemplary: the shops/showrooms are unimpeded and subdivisible spaces, as are the office floors, and the apartments—with three bedrooms and a servant’s room—are amazingly packed into 120 square metres each. Amazing because the planning is so effortless and admirably resolved. There is a strong sense of spatial flow and the layouts are almost free of corridors. Doors at the intersections of walls and facade can be opened out to create a sense of continuing space along the full length of each apartment. Circulation through the building is organised around a well that partakes of the full resonance of that word in a hot climate. Wells—for instance, India’s stepped wells— provide cool moisture, retreat from searing heat. This light well, with its ‘Islamic’ pool at the bottom creates a limpid, cool serenity. Access to apartments is ordered to ensure acoustic separation and a surprising sense of space at the core of the building. These are the first apartments I have recently encountered which, in planning terms, put Nonda Katsalidis on his mettle. Some very untraditional facilities—stacked car parking, lifts—are incorporated to effect the transformation from the old shophouse to this new model, as modified by today’s expectations of returns on investment. Those who abhor the specification of rainforest timber should consider Tay Kheng Soon’s argument that use of wood in building allows renewable resources to be brought into construction. At the July 1996 Winter School conference held by RMIT’s Centre for Design, he argued that a sustainable forest industry, properly managed for the long term, offers one way to lock in place carbon monoxides produced by burgeoning cities. Whether in an ecological context or not, this inspired building is enough to make a jaded traveller sit up and draw breath at its simple but profound delights—such as plays of passing light. That Singapore is home to this building, and to the others I have mentioned, signals a maturity in its design culture that the world would admire if only Singapore’s political and corporate masters had the wit to exploit it as systematically as do their European and Japanese competitors. Professor Leon van Schaik is the Dean of the Constructed Environment at RMIT. Genesis, Singapore |