God knows what architecture is. Is it in the detail? Does God really know? ARM Architecture’s God Knows exhibition at the University of Melbourne’s Wunderlich Gallery explores themes of negative space, the invisible, the precious and the unknown in architecture. These themes reflect the practice’s interests and design approach. As ARM founding director Howard Raggatt explained, “The architecture we like to think of is the one we don’t know, of discovery rather than of an exclusive knowledge.” The practice first used the phrase in a Braille set embedded in the exterior of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra (2001). God knows what I was expecting with this exhibition, but I was dazzled.

The exhibition is an ambitious addition to the recent Wunderlich Gallery series that takes to task the usual conventions of monographic exhibitions. Highly curated photographs and drawings are not framed and hung thematically or chronologically, nor is there an array of highly crafted models neatly propped on plinths like quasi-religious icons. This exhibition is instead a monograph of architectural ideas presented spatially. Raggatt explained that putting the exhibition together presented many of the same problems found with buildings, reflecting the way the practice works: “stumbling forward, not quite sure if something is going to work, but then having to make it work.”

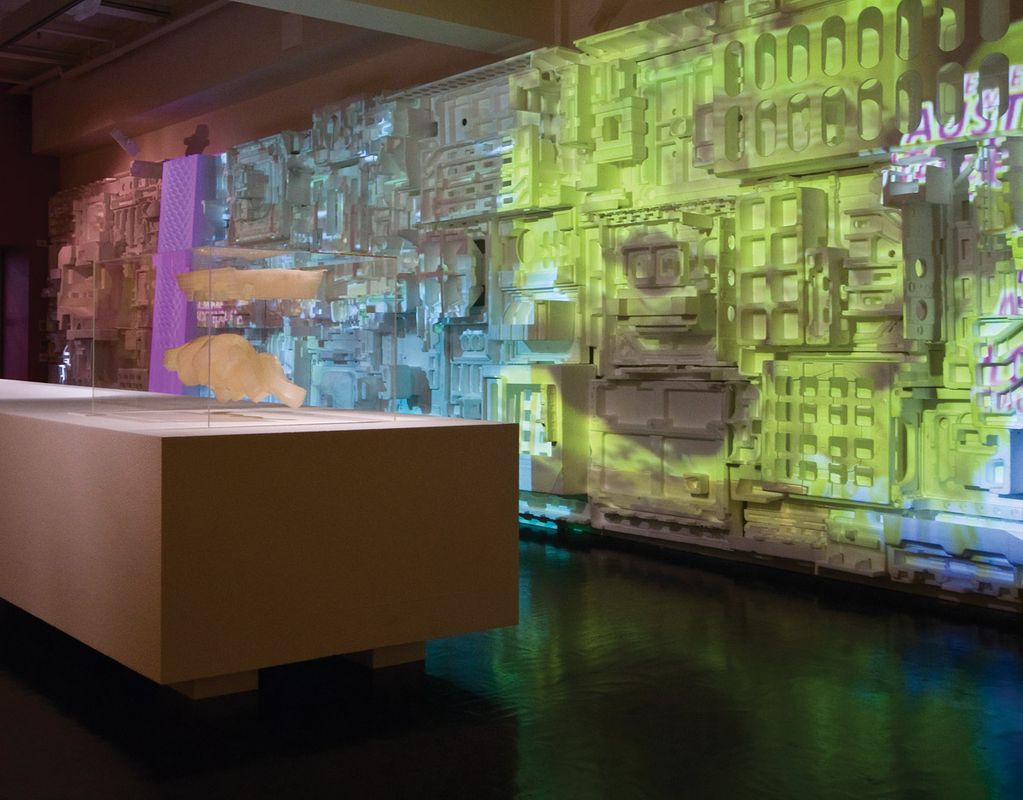

A perspective of the resin model on the bath-like form.

Image: Esther van Doornum

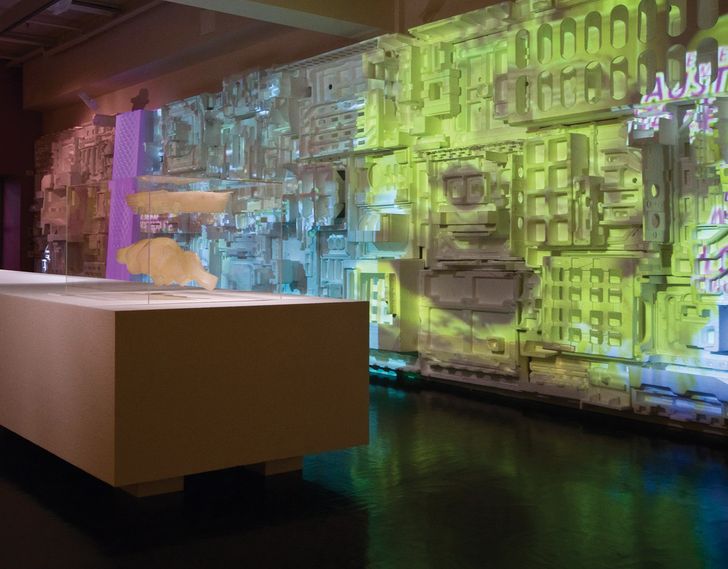

There is something for everyone at God Knows. It is visually and aurally spatial and communicates the practice’s ideas on a number of levels. Visually, you are presented with a feature wall clad in polystyrene packaging, onto which images and text are projected. Pink and yellow glossy graphics wrap around the other three walls, and a large polystyrene bath-like work forms the centrepiece, with an exquisite resin model displayed at one end. On the aural side, layers of projected voices and conversations bounce around the space.

The savvy observer will notice three polystyrene cast models of fragments of the practice’s built work on the polystyrene-clad wall, including the Melbourne Recital Centre (2008), the National Museum of Australia and RMIT’s Green Brain (2010) and Storey Hall (1995). For the untrained eye, two small screens are embedded, one displaying the practice’s built works, the other an hour-long, unrehearsed, unedited video prepared for the exhibition, featuring conversations between directors and staff about ideas and interests. The smartphone geek can also scan the QR code that enables you to view the film on your phone. At first I thought these screens were a little token, but they do serve a useful role in presenting the practice’s built work for those not familiar with it.

Overall, the polystyrene wall exudes a sense of mystery and resembles a dense cityscape that we view from a sidewards, “God” perspective. Since when did polystyrene packaging look so divine? The wall also reflects ARM’s interest in negative or void space, the invisible, the precious and the idea of casting. These ideas are prevalent in the practice’s work; the constructed void, for example, forms the invisible knot at the National Museum of Australia’s Great Hall, and the found void dominates the Melbourne Recital Centre, where the idea of something precious and something protected comes to the surface. The casting idea has a Duchampian found-object sensibility to it, but also reminded me of David Noonan’s early sculptures, where he used polystyrene packaging to cast plaster models, the complex cubic forms uncannily creating forms resembling modernist houses.

Three polystyrene cast models of fragments of ARM’s built work.

Image: Esther van Doornum

Layers of voices project phrases like “slippage on the photocopier stretches the plan,” and “you seem to be suggesting … that the design was somehow under a feminist condition.” These sync up with layered pink and yellow texts in different-sized fonts displayed on one of the screens. I recognized the voices from Raggatt’s Not Songs release, a dusty and somewhat irritating CD in my collection, but one that reflects Raggatt’s ongoing interest in texts. After some time, the voices change back to those from the ARM film that sync with the screen.

Pink and yellow glossy graphics wrap around the other three walls. One acts as a title banner for the exhibition, with the words God Knows extending across its length. It’s probably not deliberate, but this banner has a spatial quality of its own. Made up of vertical strips pieced together, each strip curves slightly at the edges and moves gently with the airconditioning, like a breathing wall. The two shorter walls display a blown-up version of the well-known Mies van der Rohe portrait. God knows, there’s always a gag in ARM’s work – the gag here is, of course, related to the idea of Mies being the god of architecture.

The central space is filled with a sublime, long, rectangular polystyrene centrepiece. At one end rests the original resin model for the Great Hall at the National Museum of Australia, where the invisible knot theme plays out. A shallow void is “carved” out of a polystyrene base to reinforce the negative theme. I thought the piece resembled a bath, but associate professor Paul Walker wandered by and said it reminded him of a coffin. Raggatt mentioned that the practice had toyed with the idea of filling the void with Kool Mints, but rumours leaked by the bemused security staff suggested it might instead be used as an ice bath at the closing drinks party. God knows what else is in store for this closing party, but the exhibition has no doubt been a resounding success, not to mention a dazzling delight.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 9 Nov 2011

Words:

Christine Phillips

Images:

Esther van Doornum

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2011