<b>REVIEW</b> John Ancher <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> Martin Walch, Peter Whyte, Ben Vos, Roger Lovell, Chris Wilson

The Georgian heritage facade of the IXL Development, on the north side of Hobart’s Sullivans Cove.

The north elevation of the IXL Apartments.

The hotel’s Art Installation Suite, in the old warehouse part of the complex, is used as changing exhibition/ gallery space and overlooks the atrium.

Martin Walch’s images of the interior of the warehouse before the renovation, now on display in the hotel.

Martin Walch’s images of the interior of the warehouse before the renovation, now on display in the hotel.

The hotel foyer.

Crisp, cool bathrooms are inserted into the heritage fabric of the hotel rooms.

Remnant wallpaper fragments in the two-level Peking Suite. This is housed in the oldest building on the site, dating from 1825. It was the residence of George Peacock, who started the jam business that grew into IXL.

The Calcutta Suite occupies the former Jones + Co boardroom, and retains the 1912 fitout.

An upper hallway in the 1920s warehouse. The void is part of the hotel’s air movement strategy. The thicker service floor floats on top of the existing warehouse structure.

Overview of the atrium, with sails beneath the striking curved roof.

The RAIA Tasmania Chapter ‘Hypothetical’, one of a series of ongoing arts events planned for the atrium.

Looking along the length of the atrium. Morris-Nunn + Associates’ office is housed at the end.

The Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra pose in the atrium.

Robert Morris-Nunn is an architectural magician who transforms his commissions into an architecture of whimsy and delight. He is, of course, aware of the tidal pull of contemporary design fashions and is conversant with current architectural theory, but he remains steadfast in his stance as a committed individual. Morris-Nunn reads the directions on current architectural guideposts, often with amusement, then responds to architectural challenges instinctively.

Hobart’s IXL Development – a project originally proposed by Morris-Nunn at the expression of interest stage in 2001 – illustrates his belief that commercially viable schemes should provide benefits to the wider community, while also functioning as environmentally responsible entities.

This gentle but obstinate architect’s determination to fight for his principles has meant that, despite the pressures for compromise raining in from all sides during construction, he can shrug and say wistfully, “We got about ninety percent of what we wanted.” ›› The development owes its impetus to the presence of heritage buildings on a prime Hobart site. In 1820, Hunter Island, close to the northern extremity of Sullivans Cove, was linked to the shore by a causeway. Its partially isolated and relatively secure location made it a logical site for storage warehouses, the first of which dated from 1825.

In 1882, a mix of the original Hunter Island warehouses and those rebuilt in the later half of the nineteenth century in the same austere Georgian style were incorporated into a jam-making enterprise. Ten years later, Henry Jones and his two partners bought out the failing business.

Over the next 35 years, Jones’s IXL brand became a household name around the world. At the time of his death in 1926, the Henry Jones and Co jam empire establishment stretched 300 metres along Hunter Street, from the purpose-built 1911 production factory at its eastern limit (now the University of Tasmania’s School of Art) to Davey Street at its western end. Many of the buildings also extended north to Evans Street, parallel to Hunter Street, one street back from the cove.

Morris-Nunn + Associates’ award-winning IXL Development is bound by Hunter and Evans Streets.

It skilfully inserts a five-star hotel into the eight adjoining warehouses that form a celebrated heritage facade of Georgian teeth facing onto Victoria Dock – the project’s major address. On the Evans Street side, a polycarbonate greenhouse wall forms the north elevation of the six-storey IXL Apartments, which is separated from the hotel by an open service yard. At the centre of the development is a glazed atrium, the public heart of the project.

In addition to these major components, a variety of other premises cluster in the development. The architects’ own office, deftly inserted into residual space, is located one floor up at the atrium’s east end. To the atrium’s north, above an exclusive clothing shop, are six studio apartments, intended to house visiting artists. On the atrium’s southern edge, below the hotel rooms, four independent retail businesses sell high quality products. Each is entered through existing warehouse doorways on Hunter Street and opens onto the atrium. A separate three-storey building, 19A Hunter Street, addresses the western end of the service yard. It houses the RAIA Tasmanian Chapter and a private art gallery at ground level, with offices and apartments above.

The IXL Development has rejuvenated the north side of the port as a prime destination for both tourists and locals, and in so doing has corrected what had become a major commercial imbalance in Sullivans Cove. In the late 1970s, the warehouses of Salamanca Place were rediscovered and adapted as an art precinct and tourist haven. At the same time, the Henry Jones and Co warehouses, 700 metres across the cove, were stripped of assets by then owners Elders IXL and put up for sale. Over the next twenty-five years they languished, becoming increasingly derelict, as their fate was debated and proposals came and went.

Today, the IXL Development is the elite face of Hobart’s tourist attractions. Hunter Street has become the preferred destination of discerning visitors and locals seeking stimulating surroundings in which to meet for coffee or lunch. Salamanca Place, with its famous Saturday market and its sideshow-alley approach to purveying Tasmanian arts and crafts as souvenirs, will always be the tourists’ Mecca. In comparison, though, Hunter Street is a revelation: vibrant, fresh and classy.

The Henry Jones Art Hotel gets its name from the management’s policy of promoting the display and sale of original artworks throughout the establishment. On entering the hotel foyer, one’s attention is arrested by two large, brooding Lindsay Broughton drawings of industrial artifacts. Constant exposure to paintings, drawings, installations and prints follows as one progresses through the building. These encounters give glimpses to inner worlds in much the same way that windows in other hotels reveal views to external places.

The hotel offers guests an internalized domain.

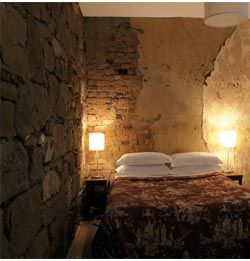

Most of the fifty standard rooms and three suites provide views through the small multiple-pane warehouse windows to Victoria Dock. You see the fishing boats and Mount Wellington well enough if you bother to investigate, but these outward views are almost an afterthought in rooms redolent of their past. The visitor’s main interest focuses on the exposed fabric of the original warehouses – the grotty stone and brick walling, the huge wonky posts and beams, the fragments of wallpaper.

Contemporary architectural impact is achieved through the insertion of two new elements into the hotel rooms – bathrooms and wardrobes. (Similar to those MN+A used at Hatherly House in Launceston, a smaller hotel project.) Both provide brilliant touches that together transform the treatment of heritage interior architecture from dutiful homage to clever reinvention. The bathrooms are alien presences, glittering containers of frosted glass and chrome. To ablute, you step into a world of hard-edged sophistication, a metaphorical cold shower. The wardrobes, designed as freestanding contemporary furniture pieces incorporated as bedheads, are less confronting than the bathrooms, but equally intelligent.

The original irregular flooring has been covered with false floors. The space enclosed is used to duct air warmed in the atrium throughout the hotel.

Most guests find this natural temperature control system to be effective and do not use the airconditioning units provided, resulting in an annual saving of $30,000.

The architecture of Morris-Nunn + Associates also always has a certain Heath-Robinson component. Devotees look for it and smile knowingly at the guru’s human touch. In this project it is found in the slightly jaded sailcloth cocoons, slung between beams to hide under-floor services in the low foyer space, which extends into the Steam Packet Restaurant.

The “art” component of the development extends into the atrium, this time in its proposed use. It is intended that “art events” will be held regularly here, thus realizing Robert Morris-Nunn’s commitment from the outset that the IXL Development should include a cultural precinct for the people of Hobart. This emphasis was part of the reason for the success of the initial development bid, and the developer also obtained a heritage grant of $1.5 million to contribute towards art and environmental design costs.

In its everyday configuration tables and chairs spill out into this public domain from two cafes, while a raised timber deck forms an extension of the hotel’s Steam Packet Restaurant.

The atrium’s most imposing feature is its glazed roof. This beautiful structure curves gently across both its short and long spans, rising from two to three storeys over its length. Its main structural components are slender steel bows. A curved timber grid housing square laminated glass panes is carried by the steel members and a fine webbing of steel rods truss the roof from below. Structural engineer Jim Gandy, who has frequently translated Robert Morris-Nunn’s concepts into extraordinary structures, has here designed an exquisitely pared-back assemblage.

Beneath the roof, triangular sails droop horizontally in languid segments, filtering direct sunlight and forming a soft overhead sculptural installation. At the edge of the atrium three huge tapered fabric cylinders suck up the warm air trapped by the atrium glass and convey it to the hotel rooms.

As in the hotel and the atrium, contextual fit has been fully understood in the IXL Development’s Evans Street edge. Here, the IXL Apartments turn their backs to the street with the contemporary equivalent of industrial élan – and in a design language that is categorically different from the slick sandstone biscuits and glass of the Zero Davey apartments which they abut.

However, if the atrium is the heart of the development, the apartments are its Achilles heel.

A new apartment block, approved as a component of a heritage project, is potentially the major profit-maker for developers keen to maximize the return on their investment – you squeeze in an extra floor if you can. The extra floor of standard flats in the IXL Apartments has pushed the two-storey penthouses too high. They can be seen clearly from the docks, a glazed and unapologetically contemporary facade protruding above half of the Hunter Street warehouse roofs. The scale of the warehouses is somehow diminished and the heritage Georgian street frontage, with its regular pattern of modest rectangular window openings, is trivialized. It hardly matters that, considered out of this heritage context, the apartments’ south facade is lively and inventive. The design philosophies clash.

Glazed apartments are designed to provide sweeping vistas. Elsewhere, users of the IXL Development are encouraged to look inward.

Understanding and fulfilling their obligations to the IXL Development’s introspective heritage has been the architects’ greatest triumph. Regrettably, with their new building, they were outmanoeuvred by the pull of market forces.

Internally, Hobart’s IXL Development is an architectural triumph. Externally, the view from the docks of a band of blatant real estate extending above Hunter Street’s warehouse roofs challenges the integrity of Sullivans Cove.

JOHN ANCHER IS A FORMER LECTURER IN DESIGN AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE.

IXL DEVELOPMENT Architect Morris-Nunn + Associates—project architect Robert Morris-Nunn; project team—Peter Walker, James Jones, Julie Payne, Kylee Scott, Ganche Chua. Project manager Stanton Management Group—Patrick Stanton.

Developer Vos Group— Harry Vos. Structural consultant Gandy and Roberts—Jim Gandy.

Electrical consultant Tas Building Services—John Calder. Mechanical consultant Tas Building services—Gosta Blichfeldt. Hydraulic consultant Gandy and Roberts—Stuart Lamont.

Acoustic consultant VIPAC—Bill Butler.

Builder Vos Construction and Joinery. Fire engineer Arup Fire—Jan Ottoson.