What should be done with land once a mining site closes? Apart from the hole in the ground, the mining town and the various infrastructures that come along with the site also need to be considered. These are questions currently being tackled across the globe. The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation (GAC) and Northern Territory government’s vision for the town of Jabiru, located within the World Heritage-listed Kakadu National Park on Mirarr Country, is a rare example of Traditional Custodians determining the future of a former mining town. “Mirarr people continue to live on our Country as our ancestors have done since time immemorial. Jabiru is built on Mirarr Country and we have a responsibility to look after the town and the people who live here. This is the Mirarr Vision for Jabiru.”1

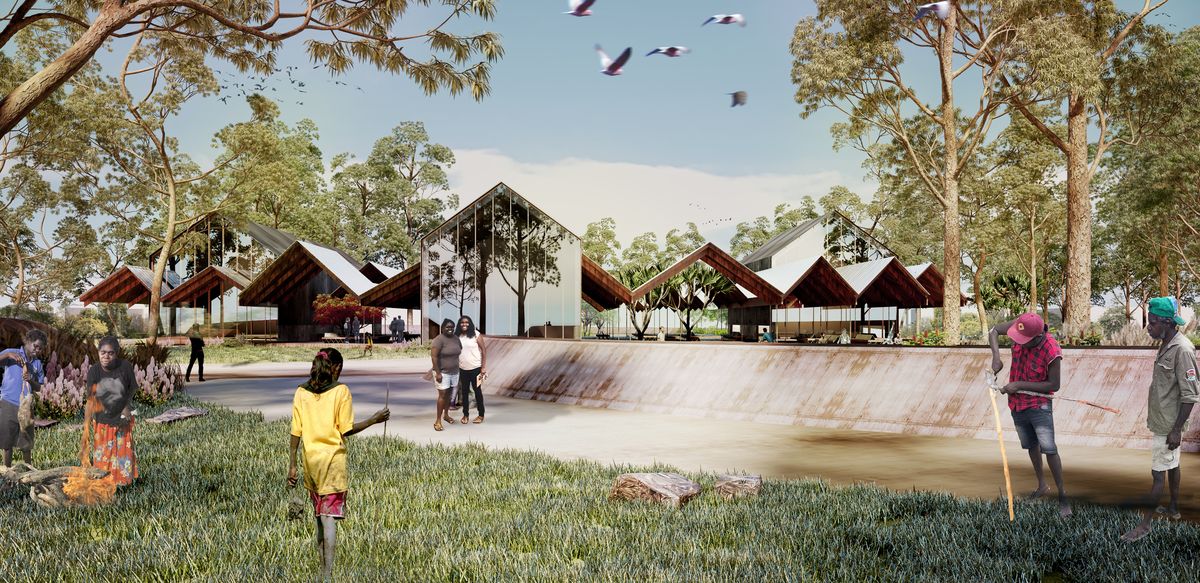

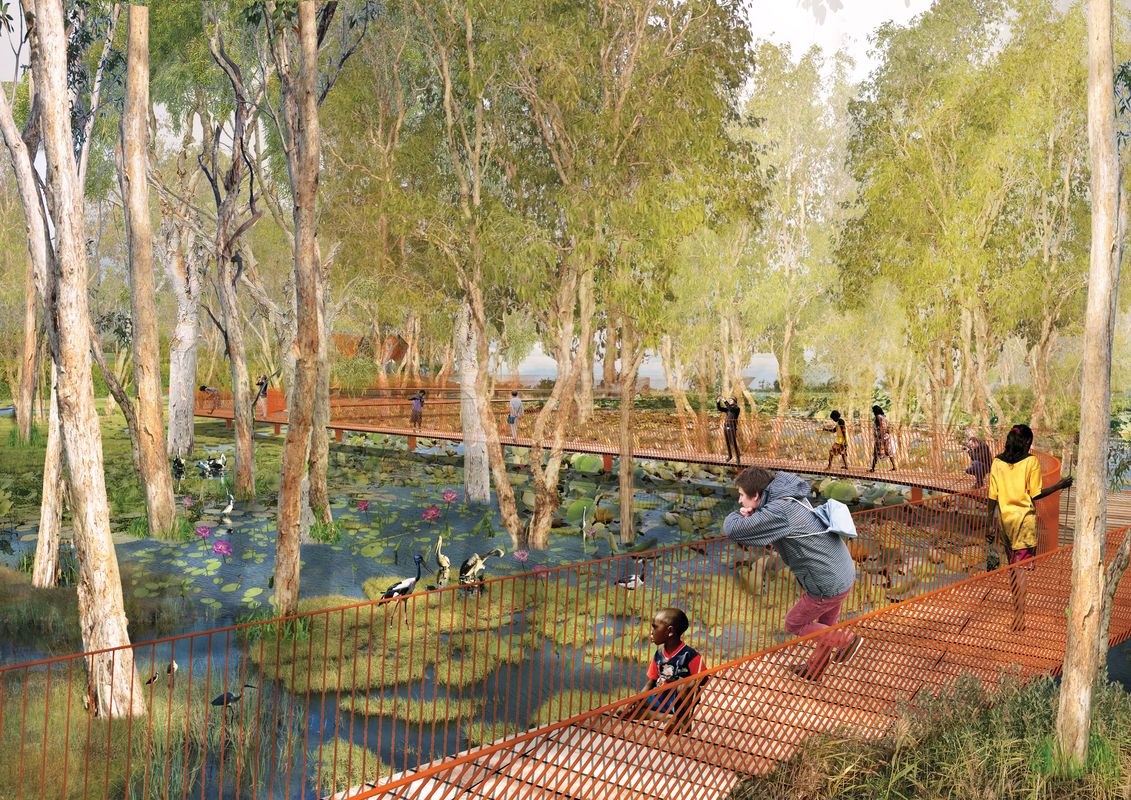

In the case of Jabiru, the GAC wanted to repurpose and transform the existing town and its infrastructure into a Kakadu National Park tourism hub. The township of Jabiru was established in 1982 to service the nearby Ranger Uranium Mine. The site includes an artificial lake currently inhabited by crocodiles, housing for the miners, a pub, a bank, council facilities, a healthcare centre, a supermarket, and other basic amenities for the miners and their families. At various times, the town also has been used by several Traditional Custodian groups from the area.

Aerial view of the Jabiru Masterplan by Common and Enlocus.

Image: Common and Enlocus

In 2021, Jabiru was formally handed back to the Mirarr people. As the Traditional Custodians and title owners, they have been driving the future of the town through Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation Jabiru Town. The corporation engaged a strategic design team to complete a Stage 1 Masterplan and business case for Jabiru: economic development and tourism planning specialist Stafford Strategy, architecture and urban design practice Common (previously known as NAAU), and landscape designer Enlocus. For the more detailed Stage 2 Lakeside Precinct Plan, this team was joined by GHD for specialist hydrological engineering input.

As John Doyle, a partner at Common, explained, the central question of the project was around “how a place that had mostly been given over to processes of extraction could be reimagined with a new economy.” The team used economic and urban modelling to determine the infrastructure required to transition Jabiru from a town built to serve the needs of the miners and their families, to a tourism-focused model designed to provide ongoing economic opportunities for the local community and Traditional Custodians.

The town of Jabiru is being transformed into a tourism hub, in line with the vision of the Traditional Custodians, the Mirarr people.

Image: Enlocus

What is compelling about this project is not simply that it is the Traditional Custodians driving the future of the town, but that the design process appears to be occurring in the form of a “yarn.” Typically, a business case is developed separately from an architectural masterplan – but in this project, the process was an iterative loop of knowledge, ideas and experiences shared between all facets of the design team and the client. Common partner Ben Milbourne described one back-and-forth involving Stafford Strategy’s economic modelling, Common and Enlocus’s architectural and landscape modelling and masterplanning, and the GAC’s direct feedback throughout the process. According to Doyle, this process was “messy, but great by virtue of that.” 2

I found that there was also a cultural and economic storytelling layer to the new masterplan. Previously, Jabiru was a turnoff on the highway before you reached the mining town. As Doyle explains, “The new masterplan recalibrates the sequence of arrival to pivot the economy away from extraction to a people-based tourism hub.” Now, as you approach the town, you experience the surrounding views toward the Kakadu escarpment, and it is clear that there is a deeper cultural narrative waiting to be discovered.

This storytelling sensibility is echoed in the programmatic arrangement of the masterplan and in reference designs for each of the key buildings developed in consultation with the Traditional Custodians. In the visualization, a suite of accommodation options sweeps around the lake frontage to serve tourists and to provide ongoing sustainable economic opportunities for the Traditional Custodians. The masterplan also includes other new community infrastructure, such as the Bininj (Traditional Owner) Resource Centre and housing; this infrastructure is all designed with sequential and incremental layers of enclosure that take their visual cues from the Jabiru landscape. For example, the proposed rammed- earth walls echo the striated geology of the escarpment. Common describes the strong relationship between inside and outside: “The [envisaged] buildings, and the programs within, are organized as a series of discrete enclosures [that] allows the landscape to flow throughout the facility, ensuring that visitors have a constant connection with the celebrated Kakadu landscape.”3

The proposed Bininj Resource Centre of the Jabiru masterplan by Common and Enlocus.

Image: Common

The building reference designs informed the development of the Jabiru Design Guidelines (2021). They also formed the basis of the brief for the first building to be commissioned under the masterplan, the Bininj Resource Centre, which has now been awarded to Ashford Group Architects.

For me as a non-Indigenous architect, the Jabiru masterplan project is not just an example of how former mining sites can be repurposed. It also demonstrates how vital the voices of First Nations peoples are in determining the future use of land, and how these voices can propel new economies that can enable ongoing sustainable, cultural and economic opportunities for these communities. Only time will tell whether this project successfully addresses the vision of the Mirarr people at Jabiru, but there are certainly lessons to be learnt from the processes used.

The Jabiru masterplan project also raises questions around how the way we practise in this land we call Australia might begin to transform, how our design processes might change and how our relationships to place and land will alter when we begin to design with and for Country. This is particularly pertinent at a time when the Australian people, through the Uluru Statement from the Heart, have received an invitation from First Nations Australians to walk together to build a better future by establishing a First Nations Voice to Parliament.

- Jabiru Kabolkmakmen, “The Jabiru Masterplan,” jabirukabolkmakmen.com.au/jabiru-masterplan (accessed 26 June 2023).

- At the time of writing, the GAC was unavailable for comment regarding its perspective on the process.

- Common, “Jabiru Masterplan,” commondesign.com.au/ Jabiru-Masterplan (accessed 4 July 2023).

Credits

- Project

- Jabiru Stage 1 Masterplan

- Architect

-

Common

Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Ben Milbourne, John Doyle, Laura Martires, Evie Blackman, Tom Muratore, Kat Fatekhova, Ronald Lau

- Landscape architect

-

Enlocus

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Cultural liaison

Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation

Development Economics Stafford Strategy

Hydrology engineer GHD

- Aboriginal Nation

- Mirarr

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Proposed

Category Landscape / urban, Residential

Type Adaptive re-use

Source

Discussion

Published online: 14 Nov 2023

Words:

Christine Phillips

Images:

Common,

Common and Enlocus,

Enlocus

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2023